June is a month associated with the struggle for LGBTQI+ rights thanks to the uprising that took place at the Stonewall Inn, New York City, in the early morning hours of June 28, 1969. The reasons that led to this uprising are still relevant today, since despite the progress that has been made, the basic rights of LGBTQI+ people are still not guaranteed.

Nineteen sixty nine was the year that homosexuals, lesbians, and transgender people rebelled against police harassment at the Stonewall Inn, a gay bar in New York, USA. This rebellion gave birth to LGBTQI+ Pride marches.

Today, particularly in the Western world, Pride marches have become more celebratory than protest-oriented. Mainstream politicians who do nothing to address the ongoing oppression of LGBTQI+ people throughout the year usually participate in these events and exploit their massive turnout, as do ambassadors of countries and CEO’s of big corporations. Meanwhile, organising and participating in Pride marches still poses a risk to the physical integrity and freedom of activists in many countries, such as Turkey and Russia. There are still countries where homosexuality is illegal, with penalties as severe as death.

While a series of rights have been won and homosexuality has been decriminalised in a number of countries, we are still a long way from achieving equal rights. Thus, a “return to the roots” of the Stonewall uprising remains necessary. But what exactly happened on the night of June 27 and the early hours of June 28, 1969? What circumstances led to the Stonewall uprising?

McCarthy and the “Lavender scare”

For most people, Senator McCarthy’s name is synonymous with the Cold War and the anti-communist witch hunt. However, alongside the “communist threat” and the persecution of left-wing people, McCarthy also engaged in a witch hunt against homosexuals. The explanation for this was as follows: LGBTQI+ people were considered “abnormal”, “sinful” and without moral barriers. These characteristics were also shared by communists, who were portrayed as being morally and spiritually “weak”. This raised the issue of “national security”: since LGBTQI+ people were forced to live a double life, it was thought that they would not be strong or loyal enough to the United States to keep government secrets. Thus, homosexuals were considered vulnerable to blackmail by communists into revealing state secrets in order to prevent their homosexuality from being exposed. The tragic irony is that this “problem” could have been solved by allowing homosexuals to be open about their sexuality, thus reducing the risk of them falling victim to blackmail. However, McCarthy had different plans, which included dismissals, prosecutions and humiliation.

The era of McCarthyism and the 1950s were therefore marked by the persecution of LGBTQI+ people and the dismissal of homosexuals from public service. They were publicly shamed and humiliated, left unemployed and some were even locked up in mental institutions after the American Psychiatric Association included homosexuality in the first edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-I) in 1952, classifying it as a sociopathic personality disorder.

The second edition of the DSM, published in 1968, characterised homosexuality as a sexual deviation.

Until the 1960s, the FBI maintained a database of known homosexuals, including their friends and relatives, as well as their addresses. Thousands of people were unable to find work during that period, and thousands more were fired. This public shaming and unemployment drove a number of them to suicide.

During the same period, homosexual “allies” were also dismissed. These were people who were not homosexual themselves, but were accused of knowing homosexuals and not reporting them.

This campaign was named the “Lavender Scare”, after the color often associated with homosexuality, mirroring the “Red Scare” for the US’s government anti-communist efforts.

An interesting point concerns the personal lives of Senator Joseph McCarthy and FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, the latter of whom was primarily responsible for maintaining the lists of “suspected” homosexuals.

McCarthy became an alcoholic, thus belonging to one of the social groups he condemned, since he believed that people with substance addictions were vulnerable to blackmail by communists.

Many biographers claim that J. Edgar Hoover was homosexual and even had an almost “marital” relationship with a younger FBI agent, Clyde Tolson, who rose through the FBI’s ranks faster than any other agent.

These two examples demonstrate that, when in a position of power, people can turn against the very rights of people they have a common identity with, since they do not experience the same oppression as the other members of the special social group to which they also belong to.

The birth of the gay rights movement

At that time, homosexuality was illegal, and many homosexuals had moved to urban centres that offered anonymity and relative safety. Persecution, dismissals and fear forced homosexuals to continue hiding. However, the first gay rights organisations began to emerge in the early 1950s, developing further in the 1960s.

One of these organisations was the Mattachine Society, which was officially founded in 1951 by the gay actor and Communist Party member Harry Hay.

The organisation’s programme focused on bringing socially isolated homosexuals together to confront discrimination as an oppressed social group, rather than as individuals. Although the Mattachine Society began with a radical programme and analysis, it did not escape the rigidities of Stalinism that Hay had brought with him from his involvement in the Communist Party. However, in 1953, more conservative forces took over the leadership. For example, in August 1956, the then organisation’s president, Ken Burns, wrote in its newspaper:

“We must blame ourselves for our own plight … When will the homosexual ever realize that social reform, to be effective, must be preceded by personal reform?”

The leadership of the lesbian organisation The Daughters of Bilitis was similarly conservative. They took their name from Bilitis, a heroine in French author Pierre Louÿs’ poetry collection The Songs of Bilitis, who is presented in the poems as Sappho’s companion.

When more militant and radical individuals began to organise within these two organisations, their respective leaderships chose to effectively dissolve their structures rather than adopt a more radical approach. Many local organisations remained and operated autonomously, with the most militant voices often emerging as leaders.

Moreover, the 1960s were marked by historic movements within the United States and internationally. The Civil Rights movement, the anti-Vietnam War movement, the women’s movement — in which many lesbians were actively involved — and important labour disputes gave impetus to the struggle for gay and lesbian rights, pushing it in a more militant direction.

The Stonewall Inn: Gay Bar, Mafia and Police

As well as the activist organisation of homosexuals and lesbians, there was a need for social interaction, entertainment and flirting. At the time, they were unable to meet, dance and flirt freely in nightclubs. This void was filled by the Mafia, specifically Tony Lauria, also known as “Fat Tony”, who purchased the Stonewall Inn in 1966 and transformed it from a bar-restaurant into a gay bar. The mafia’s involvement in nightlife dated back to the Prohibition era, so Lauria had all the right connections to establish an extremely lucrative business.

However, the Stonewall Inn was far from an idyllic meeting place. There was no running water in the bar, and glasses were “cleaned” with wet towels. There was no emergency exit, and the toilets were often clogged. The drinks were watered down and expensive. All this did not mean that patrons were safe from police raids. Lauria paid the local police station around $1,200 a week to keep the place running and ensure raids took place at specific times when there were few people around.

Nevertheless, the raids were obviously completely abusive. Police officers asked patrons for identification and, if they did not have it, they risked arrest. They also arrested drag queens, for whom the Stonewall Inn was perhaps the only place where they could express themselves, as well as women wearing fewer than three items of “women’s” clothing. In New York, it was a crime to wear clothing associated with the opposite sex. There were also incidents of female police officers entering the toilets and checking the gender of patrons.

Despite these conditions, the Stonewall Inn was a refuge for LGBTQI+ people. Not only was it the only place where homosexuals could dance together, it also provided shelter and protection to young LGBTQI+ people who had run away from home, homeless LGBTQI+ people, and so on, during its opening hours.

This did not mean that the patrons of the Stonewall Inn did not feel indignation and anger at the miserable conditions provided by mobster Tony Lauria, or at the hypocrisy of the police, who were bribed by him yet harassed the patrons.

The night of the uprising

Nothing foreshadowed the events of June 27, 1969. Apart from the accumulated anger and indignation of LGBTQI+ people at their chronic oppression, that is.

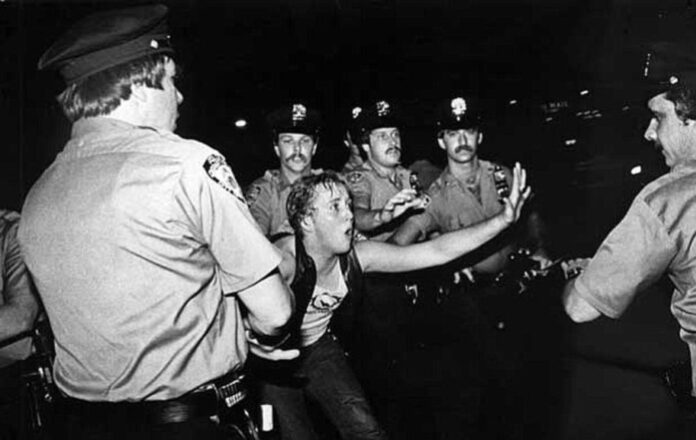

It all started with a “routine” police raid on the Stonewall Inn. The police had already made arrests and were preparing to take the drag queens and lesbians dressed as men to the police station.

Gay rights activist Craig Rodwell, who was present, described what happened next:

“A number of incidents were happening simultaneously. There was no one thing that happened or one person, there was just… a flash of group, of mass anger.”

The crowd began throwing coins at the police and then progressed to bottles, stones and other objects. Others slashed the tyres of police vehicles and cheered when the detainees were released. The police retreated into the bar, after which the rioters began to smash it up. The slogan “Gay power!” echoed through the night, and gay men, lesbians, trans people, people of all ethnicities, mainly from the working class, began to gather outside the Stonewall Inn to join the riot. However, the police were reinforced by a special security force trained to suppress protests against the Vietnam War.

Historian Martin Duberman has described the events of that night:

“In their path, the rioters slowly retreated, but – contrary to police expectations – did not break and run … hundreds … scattered to avoid the billy clubs but then raced around the block, doubled back behind the troopers, and pelted them with debris. When the cops realized that a considerable crowd had simply re-formed to their rear, they flailed out angrily at anyone who came within striking distance.

“But the protestors would not be cowed. The pattern repeated itself several times: The TPF would disperse the jeering mob only to have it re-form behind them, yelling taunts, tossing bottles and bricks, setting fires in trash cans. When the police whirled around to reverse direction at one point, they found themselves face-to-face with their worst nightmare: a chorus line of mocking queens, their arms clasped around each other, kicking their heels in the air Rockettes-style and singing at the tops of their sardonic voices:

‘We are the Stonewall girls

We wear our hair in curls

We wear no underwear

We show our pubic hair…

We wear our dungarees

Above our nelly knees!’

The next afternoon, the protesters gathered again outside the Stonewall Inn, and this time there were thousands of them. They circulated leaflets bearing the slogan, “Get the Mafia and the Cops out of Gay Bars”. The protests and riots lasted a total of five days, and nothing was the same afterwards.

In early July, a small group of gay men and lesbians began discussing the creation of a new organisation called the Gay Liberation Front. Over the following period, this organisation grew in the United States and, among other activities, its branches organised solidarity actions for arrested Black Panthers, raised money for striking workers and linked the struggle for gay rights with the struggle for socialism. Within a year, similar organisations had spread to Canada, Britain, Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, Australia and New Zealand.

The lessons of the Stonewall Inn uprising

This historic event is significant not only for LGBTQI+ people, but also for society as a whole. Social groups that were extremely oppressed and vulnerable, even within the LGBTQI+ community, played a leading role in this uprising. Black trans women such as Sylvia Rivera and Marsha Johnson were at the forefront of the uprising, despite the fact that black trans women remain among the most marginalised and vulnerable groups in the United States even today.

The events at the Stonewall Inn were discussed at length among LGBTQI+ people worldwide, but they did not remain just a topic of conversation. The following year, on the anniversary of the uprising, the first Pride marches were organised, not only in New York, but also in Chicago, Los Angeles and San Francisco. The Pride marches had just been born. These first marches were not celebrations, but clear political acts and genuine struggles for rights. In the days leading up to the marches, other events and discussions were organised.

The struggle of LGBTQI+ people was entering a new phase with greater confidence and useful conclusions. The connection between the LGBTQI+ movement and other social movements of that period was extremely important since it united oppressed members of American society and brought them face to face with their common enemy: the American government and the bourgeoisie whose interests it served.

Today, the struggle of LGBTQI+ people continues because, despite some progress in a number of countries, the fundamental issues remain unresolved. The Stonewall Inn uprising and the subsequent struggles remain a source of inspiration to this day.

In order to succeed, today’s struggles need political direction. Pride marches should be recognised as political events, not just “celebrations”. The LGBTQI+ community must link its struggle to that of the labour movement and other social movements. It must also give its demands an anti-capitalist focus because, without the elimination of capitalism and the transition to a socialist society, equal rights will remain unattainable.