We publish below the fourth part of the documents concerning the “neoliberalism debate” that took place in the ISA. This is the document of comrade VB from the section in the Spanish State representing the views of the Minority, circulated on May 2021. It was initially included in the Tendency for Internal Democracy and Unity newsletter #3.

To get the general picture for this debate, read our introduction to the publication of this material here.

You can also read the previous documents:

– Majority positions of May 2020 here.

– Minority positions of May 2020 here.

The second part of the debate:

– Majority positions of July 2020 here.

– Minority positions of July 2020 here.

The third part of the debate:

– Majority positions of November 2020 here.

– Minority positions of November 2020 here.

Neoliberalism, Keynesianism, protectionism, decoupling: What we disagree on

By Vladimir B. (Spanish State)

One of the reasons why we launched this tendency was to broaden the debate on world perspectives, where we have a range of disagreements with the majority. They concern the questions of the end of neoliberalism, of the China-US tensions and the decoupling process, and of consciousness and prospects for struggle. We are aware that it might still be unclear for many comrades what precisely these disagreements are. This document aims to provide some clarification and stimulate more comrades to engage in this debate. While all these questions are interrelated, in order to keep the text as short and concise as possible, we will deal here with the economic aspect of the debate and, in a future text, with those around consciousness, struggle and organisation of the class. Also, while this text focuses on the points of the disagreement with the majority, it also outlines alternative perspectives on the respective points, which will be developed in future documents.

For a start, we agree with the majority on several things when it comes to the topic of neoliberalism. We agree that:

- There’s been a serious loss of credibility for the neoliberal ideology in countries where it used to be strong, which started with the 2007-8 crisis and has rapidly accelerated since the start of Covid- 19.

- During this exceptional Covid-19 period, most countries have applied the kind of state intervention (massive state expenditure and budget deficits) that clashes with neoliberal ideology.

- Some sections of the ruling classes (capitalists, their political representatives, bourgeois commentators), particularly in the richest countries, are calling, for the coming period, certain policies that depart from neoliberal ideology and have Keynesian characteristics.

- There’s been a rising protectionist trend in recent years as part of a wider crisis of capitalism.

- The decoupling process between China, on the one hand, and the US and some of its allies, on the other, will be an important feature of the new period.

But we disagree that all this is enough to conclude that it’s the end of neoliberalism or of the neoliberal era. We understand neoliberalism primarily as a policy framework commonly centred around austerity, privatisation, outsourcing, financialisation, deregulation, precarisation of labour and ‘free’ trade, although the consistency with which these policies have been applied has varied from country to country and from period to period. As comrades correctly point out, these policies are not original to neoliberalism, but neither is neoliberalism itself. As we have stressed in previous documents, the main tenets of neoliberalism are in fact what capitalism looked like for most of its history, a revival of what in the 19th century was called ‘laissez faire’ (hence the prefix ‘neo-’).

Thus, the end of the neoliberal era would mean – chiefly among other things – that massive state expenditure (which we saw in the course of 2020) would become dominant in relation to ‘fiscal consolidation’ (aka austerity) on a permanent or long-term basis. That is what the World Perspectives document voted at the recent IC claims: “the dominant trend in the world economy will be towards intense state intervention — politically and financially — with less weight given to the classical “neoliberal” dogma of cutting deficits”.

However, we don’t see enough evidence that this will be the case. We believe that the current character of state intervention (i.e. massive fiscal deficits, borrowing and a rise in public debt) is not of a permanent or a long term nature, but an emergency response to the external shock brought by the pandemic and the depth of the economic crisis. We believe the growing levels of debt and inflation will force most capitalist governments to resort again to austerity as early as this year, as illustrated below.

For example, even in the UK (the 6th richest country in the world), the Tory government’s budget for 2022-2023 is set to spend £14bn less on public services than planned before Covid. On top of that, the £1.5bn green homes grant has already been scrapped only 6 months after it was launched. As an economist from the otherwise neoliberal think tank Institute for Fiscal Studies put it, “Plans can change but, as things stand, for many public services, the first half of the 2020s could feel like the austerity of the 2010s.”

In the Eurozone, the fiscal rules have been suspended but only temporarily, in contrast to what comrades in the majority seem to imply. At the last OECD meeting, Germany’s representative stated that, in countries like Spain, “fiscal consolidation process should start sooner rather than later”. Also, a recent Economic Bulletin of the European Central Bank concluded that “the fact that debt levels have risen dramatically means that it is crucial for euro area Member States to have credible fiscal consolidation strategies in the medium term”.

In some EU member states, further neoliberal measures have already been announced. One example is Sweden, where in January this year the parliament approved – as pointed out in an article on our international website – “73 neo-liberal policies, going even further in their attacks on workers’ rights and welfare than even the right-wing alliance government in 2006–14 dared to do”. In Spain too, only the other day, the ‘progressive’ government has pledged, in exchange for EU funds, to turn public highways into toll roads in 2024. This is just a sample of the kind of neoliberal conditionalities that the EU recovery funds are likely to entail.

In the neo-colonial countries, the return to austerity is even more likely to happen with all the more devastating effects. A EURODAD report last year showed that, out of the 80 countries that received IMF assistance since the start of the pandemic, “72 countries are projected to begin a process of fiscal consolidation as early as 2021”. A more recent report confirms this trend, at an even larger scale: “The analysis of IMF fiscal projections shows that budget cuts are expected in 154 countries this year, and as many as 159 countries in 2022. This means that 6.6 billion people or 85% of the global population will be living under austerity conditions by next year, a trend likely to continue at least until 2025.”

Comrades in the majority often invoke Brazil and India as examples that the neoliberal era is ending even in some parts of the neo-colonial world. While these gigantic countries have more scope for state intervention of the kind described above than most neo-colonial countries, they will still see austerity coming back in full force. The IMF’s World Economic Outlook from April this year forecasts that Brazil will cut public spending this year by nearly 6% of the GDP (more than the 5.4% increase last year due to Covid- 19), while India is set to make successive cuts every year from now till 2025. The continuation of neoliberalism will not be limited to austerity, as Modi plans to privatise banks, which would be a first for India since 1969.

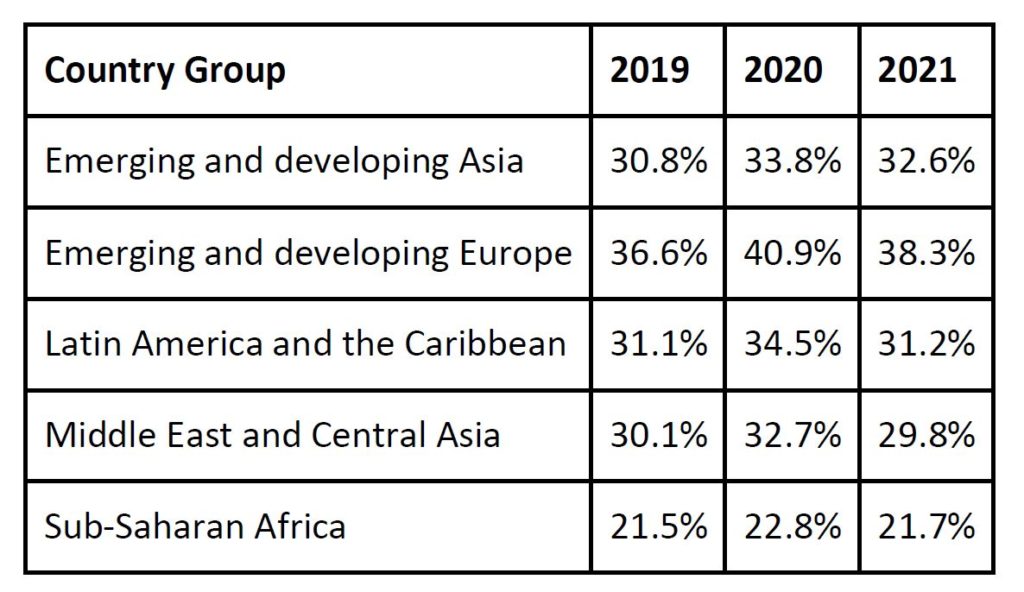

At a more abstract level, comrades in the majority argue that, just like the emergence of neoliberalism itself (which spanned over more than a decade), its ending would not be an even and quick process. That’s true, it wouldn’t. But saying that is just a way of begging the question. We first need to actually prove that this process has indeed started. The available evidence indicates it has not and that the kind of state intervention that we saw in response to Covid-19 will not become the dominant economic policy in most countries in the world, which in turn will experience austerity as of this year. The table below, based on IMF data from April 2021, forecasts a reduction in public spending this year compared to 2020 in all the groups of low- and middle-income countries. In some of these macro-regions public spending, on average, will drop very close to the pre-pandemic levels (Latin America and the Caribbean, Sub-Saharan Africa) or even below those levels (Middle East and Central Asia).

Comrades in the majority often respond to this by saying that austerity is not unique to neoliberalism. That is true. Austerity was practiced, at times, also during the post-WWII Keynesian era (in contradiction with Keynesianism itself) or even in some of the planned economies from the former Stalinist states. But it was not the dominant fiscal policy. State induced austerity, through massive cuts in public spending as a systematic policy applied on an international scale, is essentially a characteristic of the neoliberal era.

The US is, at the moment, the most advanced example of a shift away from neoliberal fiscal policy, as Biden’s two investment plans, American Jobs Plan and American Families Plan amount to a total of around $4 trillion. Comrades in the majority have relied heavily on the case of the US throughout the debate, saying that we need to focus on the most important countries, as they announce the direction of travel for the rest of the world. The World Perspective document voted at the last IC meeting from February suggests that this direction of travel “shows similarities to the Keynesian-like methods & state intervention as applied in the 30ies” (which, just to be clear, we all agree that are not pro-working class but meant to prop up the capitalist system).

Even in the case of the US, we shouldn’t take Biden’s investment plans at face value. According to a recent report by The Economist, the most probable scenario is that only about half of the proposed investment sum will pass through the Congress. But even if it does pass in its current form, federal spending (excluding military expenditures) will reach 4% of the GDP, which is about half of the average during the 1930s. Indeed, Biden wants to raise corporate tax to merely 28%, which is less than it was before Trump came into power.

Another main argument used by the majority comrades is around the rising protectionist trend in recent years. The trend is undeniable. But we disagree that it has become or is likely to become the dominant trend in the world economy. While the world merchandise trade volume dropped by 5.3% (less than expected), the rebound has already started towards the end of 2020, with an expected increase of 8% this year alone. Moreover, the drop from last year was largely due to the external shock represented by the pandemic rather than by conscious protectionist measures. As a matter of fact, a WTO report from November 2020 showed that “Of the 133 COVID-19 trade and trade-related measures recorded for G20 economies since the outbreak of the pandemic, 63 per cent were of a trade-facilitating nature and 37 per cent were trade restrictive.” This is particularly relevant as it is precisely the G20 economies that have been responsible for the protectionist trend in recent years.

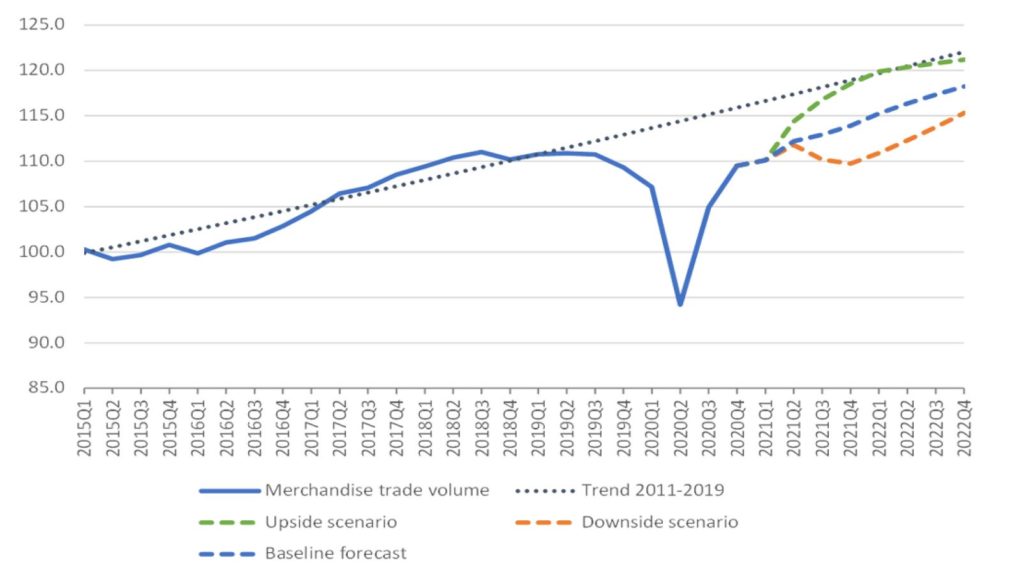

But when we discuss world perspectives and the key features of an era, we need to look at the broader picture. What does this picture show us? That – as illustrated in the chart below – between 2015 and 2020, when the pandemic started, the world merchandise trade volume increased by 10%. The chart also makes two forecasts for the coming period, an optimistic (in green dotted line) and a pessimistic one (in orange dotted line). Even the pessimistic one anticipates the volume of trade to surpass the pre-pandemic level over the next two years. This growth is not compatible with protectionism becoming the dominant trend in the global economy.

Also, in January this year we’ve seen the launch of the African Continental Free Trade Area, signed in 2018 by 54 countries and ratified since by 34 of them, which commit themselves to eliminate tariffs on 90% of products within the next five years. Furthermore, last year we saw the signing of several trade deals that, if ratified, would further fuel neoliberal globalisation:

- Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership between 15 countries in Asia & Pacific – including China – would become the world’s biggest free-trade agreement by population and GDP, entailing the elimination of 90% of existing tariffs.

- Comprehensive Agreement on Investment between the EU and China, which among other things would enable market access to EU companies in China.

- UK-EU trade deal, which allows for tariff-free trade in goods. Indeed, the UK’s new Global Tariff is, among other things, “scrapping unnecessary tariff variations, rounding tariffs down to standardised percentages, and getting rid of all “nuisance tariffs” (those below 2%)” and “ensures that 60% of trade will come into the UK tariff free on WTO terms or through existing preferential access from January 2021”. All this indicates that Brexit was less about protectionism than, in fact, more deregulated ‘free trade’.

Obviously, some of these deals, particularly those involving China, already face significant obstacles. However, we should not simply dismiss these deals due to these obstacles. And we should ask ourselves: what does the fact that these deals, some of which had been negotiated for several years, were all signed last year, say about the underlying trends and counter-trends in the world economy today? Comrades in the majority have not answered this question so far but simply found reasons to dismiss the deals altogether. We believe they represent a further indication that the objective need of capitalist classes for world trade still prevails over protectionist considerations.

Entire regions are too embedded in the international supply chains to afford a great deal of protectionism. In Central and Eastern Europe, for example, trade represents over 100% of the GDP in Belarus, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czechia, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Poland, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia. Taking the world as a whole, between 2016 and 2019, trade as part of the GDP has gone from 56% up to 60%, part of a historical upward trend that in 1970 was at only 27%. This is just one expression of the deepening and widening of economic interdependence that has been taking place over the last half a century. It’s a qualitative leap in globalisation that makes comparisons to previous protectionist eras (e.g. the 1930s) inherently problematic. For instance, a qualitative difference to world trade in the 1930s is that in recent decades we’ve witnessed the rise of Intra Industry Trade (IIT), meaning that one country is simultaneously importing and exporting goods in the same industry, which in turn is a further reflection of the deep and complex integration of supply chains.

It is this economic interdependence that will also limit, in our view, the process of decoupling between China and the West, the US in particular. There is an essential difference between the old Cold War and this new one: the US and China are much more economically integrated. For example, in 2018, Apple alone had 380 suppliers in China and, since then, only a few of them relocated from China. For China provides not only cheap and non-unionised labour, but also the kind of highly skilled labour that is not to be so readily found elsewhere. Even Trump, despite the belligerent rhetoric, eventually failed to blacklist Chinese tech titans like Alibaba. As a reflection of this economic integration between the two superpowers, a recent article on the ISA website points out that “Based on the new U.S. stimulus package, UBS bank has upgraded its forecast for China’s export growth this year from 10% to 16%”.

What this shows is something that comrades in the majority often acknowledge but largely fail to factor in when they put forward their analysis: that the US capitalist class is split on the question of China. Such splits within and between different capitalist classes will be a hallmark of the new period. We can see that also among US’ traditional allies: if countries like the UK or Japan seem, at least for now, to follow the US’ geopolitical lead with respect to China, countries like Germany (the powerhouse of European economy and most influential EU member state) have spoken against decoupling. As the German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas put it after a meeting at the end of April with his Chinese counterpart, “we need strong, sustainable communication channels with Beijing. Decoupling is the wrong way to go.” This comes after already in November 2020 Germany lifted the ban on Huawei’s 5G infrastructure – something that even some of Huawei’s direct competition, such as the Swedish giant Ericsson, has been calling for.

To conclude, we disagree that we are witnessing the end of the neoliberal era. This doesn’t mean we believe it will be business as usual and that neoliberalism will simply continue as before. Instead, we believe that neoliberalism as a policy framework (which we need to distinguish from the neoliberal ideology, which is itself not that homogenous) is versatile enough to include – as it has done in the past, even in the US under Reagan – Keynesian-like and protectionists policies, although that will mostly be the prerogative of the richest countries. But even in most of those rich countries, not to mention the neo-colonial world, austerity and ‘free trade’ will largely remain dominant in relation to state investment and protectionism respectively. Other key neoliberal policies will also continue to prevail: privatisation, outsourcing, financialisation, deregulation, labour precarisation.

Finally, we think an important adjustment that neoliberalism is already going through is from a political rather than economic point of view: an increasing divorce from the tenets and institutions of liberaldemocracy, a shift from ruling by ‘consent’ to ruling by ‘coercion’. We believe we need to collectively analyse and understand better this authoritarian turn, displayed even in ‘advanced democracies’ as the US, the UK or France in the form of a strengthening of state repression and a clampdown of individual rights. This trend will also be a central feature of the new period and is explained precisely by neoliberalism’s loss of legitimacy and people’s increasing anger towards neoliberal policies. We will explore these questions in future documents.