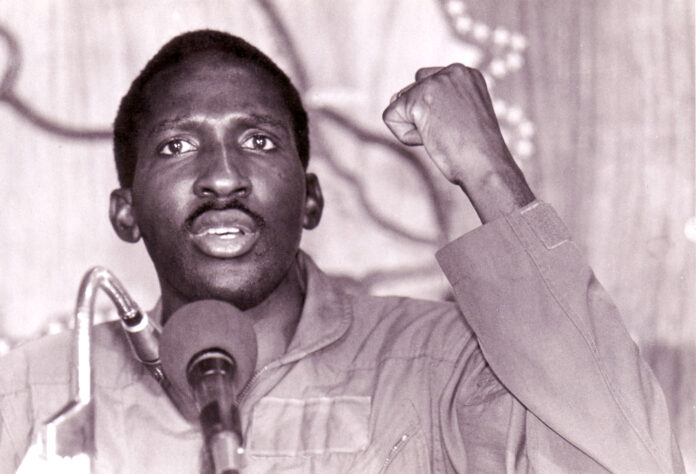

On October 15, 1987, the President of Burkina Faso, Thomas Sankara, was assassinated in his office, along with twelve of his colleagues. The main person responsible for the assassination (for which he was convicted in the spring of 2022 but never punished, as he has been living in neighbouring Côte d’Ivoire since 2014) was his former close associate and personal friend Blaise Compaoré, who seized power in a coup d’état in close collaboration with the French government.

The interests of the French ruling class were also the first to be threatened by Sankara’s left-wing government, which had at its heart the improvement of the living standards of the poor and the economic decolonisation of the country.

These interests were also the first to be restored by the Compaoré regime. Sankara was a danger because the example of Burkina Faso, especially as reforms progressed and living standards continued to improve, could inspire societies and movements in neighbouring West African countries, i.e. the other former French colonies in the region.

Sankara’s pro-people policies, his reforms, his choice to live as poorly as the average worker and his total devotion to his people made him a symbol of struggle for the peoples of Africa in particular.

The short history of his rule (four years in total), as well as the history of his assassination, is an important part of the history of the struggle of the peoples of Africa for meaningful independence. This struggle is still ongoing.

From colonialism to ‘independence’

In 1896-97, the region of present-day Burkina Faso was conquered by France and was included in a series of colonial possessions in West Africa, along with parts of present-day Mali, Niger, Senegal, etc. The region was called Upper Volta. It was named Upper Volta by the colonialists because the Volta River, much of which lies in Ghana, originates in the mountains of Burkina Faso. The name “Upper Volta” refers to the country in which the upper part of the river is located. The area remained in the possession of France until 1960, when it gained independence.

This was the time of the great anti-colonial uprisings that swept much of the African continent and many parts of Asia. Recognising that they could no longer hold their colonies by the force of arms, the major imperialist European powers were forced to grant independence to most of them, while seeking new methods of maintaining economic and political control over them.

In the almost twenty-five years between the country’s formal independence (1960) and the rise to power of Thomas Sankara (1983), Upper Volta was ruled by presidents who maintained close ties with the West and were often at odds with workers’ demands and movements. In 1983, a military coup led by B. Compaoré overthrew the military government of Jean-Baptiste Ouendraogot and brought Sankara to power, with Cabaoré himself as his main collaborator.

The army at the service of society?

After leaving school, Sankara opted for a military career and was soon sent to Madagascar to continue his military training, where he was inspired by the workers’ and youth movements of the time.

And while the army in a capitalist society exists to defend the interests of the ruling class against the enemy within – that is, the popular classes – as well as against its rivals abroad (either to defend or expand its borders and dominance), Sankara envisioned an army that would work for the benefit of the people and of society. An army that would be politically and ideologically trained to serve not the interests of the capitalists and their rivalries among themselves, but the interests of the working and rural poor. Some years later, being at the time in the leadership of Burkina Faso, he said:

“When you are bearing arms that can spit fire and death and when you can receive orders standing to attention in the front of a flag without knowing who will benefit from this order or this arm, you become a potential criminal who is just waiting to spread terror around you. So a soldier without any political or ideological training is a potential criminal”

What he envisioned in relation to the army could not, of course, be realised without the overthrow of the capitalist system, which uses armies as tools to protect its interests. Just as the impressive changes he promoted in other sectors of society could not survive for long without being mercilessly attacked.

Unprecedented reforms

Sankara was an inspirational figure for numerous people both within his nation and around the world due to two primary factors.

First, his self-abnegation and his readiness to lead a life akin to that of the people he urged to make sacrifices in the pursuit of constructing a self-reliant nation with an infrastructure designed to cater to society’s needs. Throughout his tenure, this self-abnegation materialized as a modest way of life he adopted personally and also enforced on the broader government.

Luxury cars for ministers were abolished, first-class air tickets were also abolished, and the highest-paid government officials were asked to donate one month’s salary a year to help build the country’s infrastructure. Corruption and personality cults, key elements of most African governments, which at the time acted as puppets of the former colonialists, were systematically combated.

The second factor was the radical policies and pro-people reforms that have been implemented, which drastically changed the country’s image on a number of levels.

In terms of women’s rights, Sankara’s government outlawed dowry, polygamy, forced marriages and clitoridectomy, and appointed women to key government positions for the first time.

On the environmental front, which at the time, with few exceptions, was considered a tertiary issue even by the most ‘enlightened’ sections of the left and movements at a global level, strict measures were taken to protect and restore forests, with the main aim of combating desertification.

Among the most impressive results were those in the health sector, with a massive vaccination programme against diseases such as meningitis, measles and polio, vaccinating an estimated 2.5 million children in a matter of weeks.

In the cities, housing programmes were implemented for the slum dwellers, while an extensive railway network was built throughout the country. Agricultural production was greatly increased and the consumption of local products was encouraged, in a move towards economic independence from the imperialist powers.

The debt conflict

In 1987, at a meeting of the Organisation of African Unity in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, Sankara addressed the continent’s other heads of state and called on them to default on their debts to the World Bank.

He said the rich had no right to make such extortionate demands on the poor:

“Who here doesn’t wish for the debt to be canceled outright? Whoever doesn’t, can leave, get into his plane and go straight to the World Bank to pay! … I would want our conference to take on the urgent need to plainly say that we cannot repay the debt.”

“We think we don’t have the same morality as others. The rich and the poor do not have the same morality. The Bible, the Koran cannot serve those who exploit the people and those who are exploited in the same way.”

These positions, which had little hope of finding support among the government representatives of other African countries, would certainly reach the ears of the poor and oppressed in Burkina Faso, and certainly in the rest of Africa. And this was of great concern to the lenders – the former colonialists.

This government could no longer be tolerated and plans were made to overthrow it shortly afterwards, in October 1987.

Subversion and cover-up

Sankara’s assassination and Compaoré’s seizure of power came as a shock to many in the country. Initially, the assassination itself was presented as a natural death (although his exhumation in 2015 revealed that he had been shot at least 12 times), and its perpetrator never stopped pretending to be an innocent man mourning his friend.

Gradually, the country’s population saw the progressive reforms of the previous four years rolled back and relations with the French government restored. Compaoré ruled Burkina Faso until 2014, when corruption and authoritarianism overflowed the cup after 27 long years.

The people took to the streets en masse, torching the parliament and ousting the hated president. But this was not enough to bring about meaningful change in the lives of the country’s poor, working people and youth. The governments that have come and gone since then are once again a mixture of corruption, authoritarianism and the handing over of Burkina Faso’s wealth to big business in what is now global, modern colonialism. Although the recent coup in Burkina Faso has distanced it’s government for French imperialism, it has not solved any of the underlying crises that people in this country face.

There is no good news on the justice front either. Blaise Compaoré was only convicted of Sankara’s murder in April 2022, which of course means practically nothing as he has been living in Côte d’Ivoire since 2014. He even recently made a trip of several days to his country, where not only was he not disturbed by anyone, but he went as a guest of the then “military leader” of Burkina Faso, S. Damiba, as part of the “national reconciliation”.

Left-wing coups

Ultimately, the way in which Sankara took over the leadership of the country showed the limits of his effort very early on. His rise to power was not the result of a popular uprising, it was not based on the mobilisation of the grassroots, even though the people were very supportive about his policies.

Sankara became president of Burkina Faso in a military coup – and while this coup had progressive/liberal features, the lack of organised participation by workers, the rural poor and youth in taking and maintaining power made his government vulnerable to the subsequent coup.

We have seen similar scenarios in the past in a number of countries around the world, particularly in Africa and Latin America. Members and sections of the army are moving towards overthrowing existing reactionary governments and seizing power in order to defend the rights of the workers and the poor. This is part of the political tradition in several regions of the world.

The basic problem of this tradition is the attempt to impose pro-people measures from the top down, without the active participation of society, the popular strata and their organisations.

In the case of Burkina Faso, society participated massively in the reconstruction of the country from colonial underdevelopment, building the necessary infrastructure with its own hands, from the railways to agricultural production. But it did not have the organisation in the workplaces and neighborhoods, it did not have the structures necessary to enter into the struggle to defend a left-wing government that would sooner or later be attacked.

Thomas Sankara gave his country the name Burkina Faso, which means ‘land of honest men’. But his story is a tragic reminder that honesty and self-sacrifice, while necessary, are not enough to deal with a ruthless system. In the end, the only force that can defend the social gains is the popular layers themselves, the workers, the poor peasants, the youth, those who play an active role in the struggles against the ruling class, once power has passed into their hands through workers’ and people’s councils- what we call workers democracy.

The country of honest people in the hands of dishonest people

Today, Burkina Faso is in the hands of corrupt political and military leaders, and its population of around twenty million is sinking deeper into poverty and insecurity. It is the eighteenth poorest country in the world, with an average annual income of $790/€810 (2022 figures).

At the same time, the country has significant mineral wealth, particularly gold, which is exploited by large multinational mining companies. People of all ages (from adults to very young children) work in mining and processing under the most dangerous and unhealthy conditions, while the environment in which they live, their water and their crops are polluted by the toxic waste from this processing.

The only viable future for the poor in Burkina Faso, as in the rest of Africa, is to overthrow the power of big business, the old and new colonialists and their corrupt local collaborators.