The rise of far-right and even neo-fascist parties across Europe and in other parts of the world, has become a political reality in in recent years. The far-right, in all its manifestations is no longer a fringe movement in many countries but is actually in government in: Argentina, Italy, Hungary and other countries. Trump looks likely to be the next President of the US and other far-right figures have a chance of power at the next elections elsewhere. In 15 of the 27 EU countries, the far-right has a double-digit share of the vote, in many of them over 20%. In the next European elections, according to all the polls so far, the far-right parties are on the rise and could win 25% of the seats in the European Parliament. In the three largest EU countries, according to the polls, the far right is likely to come first in France and Italy and second in Germany.

The UK appears to be bucking this trend, with support for the Conservative Party in free-fall and a Labour government almost certain at the next election. The right wing Reform UK is taking votes from the Conservatives, rather than Labour and will weaken the Conservatives, but is unlikely to win many seats at the next election, as was the case with UKIP – the party it emerged from. Currently, Reform stood at 10% in a recent Savanta poll conducted between the 23 – 25 February, with the Conservatives on 26% and Labour 44%. This article is an attempt to look at social attitudes as well as political trends around far-right and racist ideas in the UK. It will look in some detail at attitudes to race and difference and then attempt to draw some political points. It is not an attempt to look in depth at political thinking but rather to draw conclusions around social attitudes on race and difference. The patterns of support for different political parties will be considered, in the context of social attitudes.

Hate crimes and transgender people

Looking into levels of racism and prejudice is a subject fraught with complexity because there are different measures of racism and prejudice. A fairly concrete measure might be considered to be the incidences of Hate Crime, which are reported annually by the police. However, the reporting of such crimes does prove problematic. Trust in the police to act on such reports is low and this could vary across the different categories: race, religion, sexual orientation, disability and transgenderism. The police themselves accept that there is an under-reporting of hate crimes but also claim that over time the numbers have become more reliable. There also tends to be a higher level of hate crimes reported, than would be suggested from other data. There are longitudinal studies, conducted by the British Social Attitudes Survey and Ipsos, as well as non-longitudinal studies, which I will refer to in this report, but I would contend that although the results of these surveys are suggestive of trends, they are not conclusive. I will therefore preface this report with a cautionary warning. However, I do not subscribe to a post-modernist view that no data can be trusted. One has to read the data with care and consider other societal issues alongside the data, which includes ones’ own lived experience.

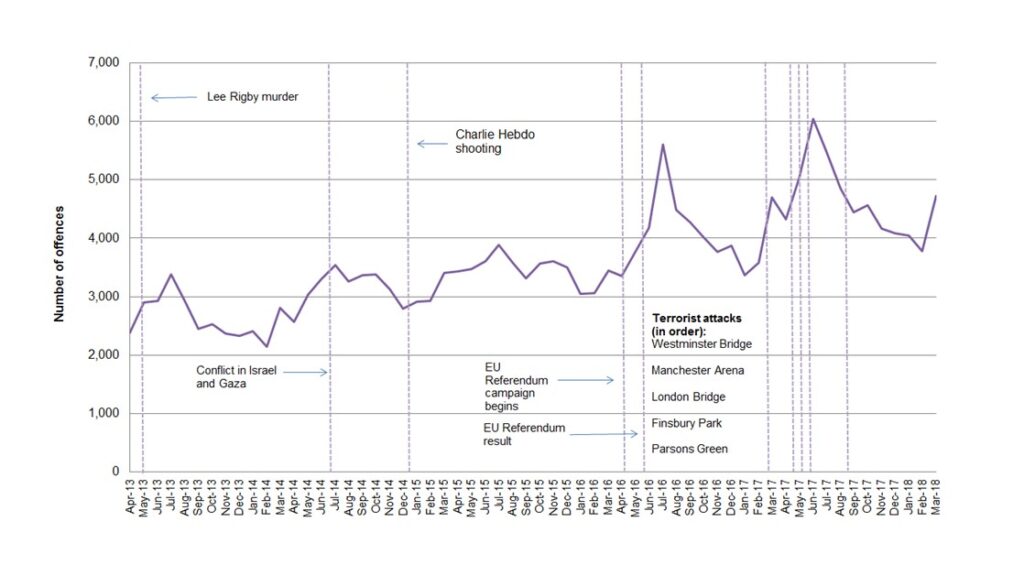

Therefore, taking into account the above caveat, the data trends around attitudes to race and other forms of prejudice in the UK, reveal some small grounds for optimism. 2023, for example, was the first year since records began, that racially motivated hate crimes decreased. There was also a decrease in other forms of hate crime: religious, sexual orientation and disability. The only form of hate crime that increased in frequency was transgender hate crime. Hate crime data tended to present a more negative picture of attitudes towards minority groups than other data gleaned from longitudinal studies, such as the British Social Attitudes Survey, but also empirical observation of the reduction in hostility to other minorities, especially in the 1990s. The decline in support for extreme, racist groups such as The National Front and the British National Party was also apparent. Although the UK went through the Brexit referendum, which was identified as a possible source of increased racial tension by many on the Left, the effect of negative attitudes to race were temporary.This can be seen from the table below as well as deduced from other surveys, as we shall see later. The impact ofattacks identified as terrorist attacks appears to have had as much effect on incidences of hate crime, as Brexit, but again the effects were of limited duration.

The fall in numbers of hate crimes across four of the five areas of hate crime is a cause for some positivity, but the significant rise in the numbers of transgender hate crimes is cause for concern. Incidences of transgender hate crimes were previously rather low and public attitudes in the UK towards transgender people were relatively positive. In recent years those attitudes have deteriorated and this can be seen from the number of transgender hate crimes compared to other forms of hate crime listed in the table below.

| Numbers and percentages | England and Wales, excluding Devon and Cornwall | |||||

| Hate crime strand | 2018/19 | 2019/20 | 2020/21 | 2021/22 | 2022/23 | % change 2021/22 to 2022/23 |

| Race | 77,850 | [x] | 90,909 | 108,476 | 101,906 | -6 |

| Religion | 8,460 | [x] | 6,288 | 8,602 | 8,241 | -4 |

| Sexual orientation | 14,161 | [x] | 18,239 | 25,639 | 24,102 | -6 |

| Disability | 8,052 | [x] | 9,690 | 13,905 | 13,777 | -1 |

| Transgender | 2,253 | [x] | 2,728 | 4,262 | 4,732 | 11 |

| Total number of motivating factors | 110,776 | [x] | 127,854 | 160,884 | 152,758 | -5 |

| Total number of offences | 104,765 | 112,633 | 122,256 | 153,536 | 145,214 | -5 |

The above data coincides with data from the British Social Attitudes Survey, which reveals that, attitudes towards people who are transgender have become markedly less liberal over the past three years. The survey carried out in 2019 reveals statistically significant differences from recent figures (2023).

64% describe themselves as not prejudiced at all against people who are transgender, a decline of 18 percentage points since 2019 (82%).

Just 30% think someone should be able to have the sex on their birth certificate altered if they want, down from 53% in 2019.

While women, younger people, the more educated and less religious express more liberal views towards people who are transgender, these views have declined across all demographic groups.

The above responses are in contrast to a liberalisation of attitudes in other areas and have been generated by an onslaught on the trans community, led by JKR Rowling, the author of the Harry Potter books, but also by some feminists and others on the Left, who have identified the transgender issue as problematic. In the UK it is an issue that has been thrust forward and led to intense rhetorical attacks on those with differing views from both sides. The issue of safe spaces for women has been side-lined in many of these clashes and the rights of trans people to identify their gender brought into question, when previously it would have been widely seen as uncontroversial. It is not the purpose of this piece to explore this issue in detail but to highlight the significance of more negative attitudes towards it, that do not reflect the general trend of improving attitudes toward other minorities. It also points to the rapidity with which attitudes can change, especially if Left voices begin to influence the discussion, alongside right-wing voices.

Attitudes towards race

On the other hand, recent research from Ipsos on attitudes to race and inequality in Britian, reveals that the British public has become avowedly more open minded in their attitude to race since mid-2000s.

Some of the key findings are that:

The vast majority, 89%, claim they would be happy for their child to marry someone from another ethnic group, and 70% strongly agree. This is an improvement from January 2009, when 75% said they would be happy overall, and 41% strongly.

Similarly, the vast majority (93%, nearly all of them strongly disagreeing at 84%) disagree with the statement that, “to be truly British you have to be white”. In October 2006, 82% disagreed, 55% strongly. The proportionwho agrees with the statement has fallen from 10% to 3% in the last 14 years.

Although these findings are cause for optimism, this does not mean that people’s perception of race is entirely positive and there are still major concerns about racial tension and an acceptance that the UK still has a long way to go in terms of being a fully open and tolerant society. New polling by Focaldata, with a large sample of Black Caribbean and other ethnic minority respondents finds a balanced attitude towards the progress made on race.

The key findings were:

Some 71% of the public and 68% of ethnic minorities agree that “The UK has made significant progress on racial equality in the last 25 years”.

But 80% of ethnic minorities and 66% of the public as a whole agree that “The UK needs to make much more progress on racial equality in the next 25 years.”

But 67% of ethnic minority respondents agree that “Black and Asian people face discrimination in their everyday lives in Britain today,” while only 10% disagree.

A major new survey of racism and ethnic inequalities, the Evidence for Equality National Survey (EVENS), produced in 2023, by Kings College, London, reveals the extent of racism and racial discrimination experienced by people from ethnic and religious minority groups in Britain. This is not a longitudinal study, but does reflect current perceptions and underlines the fact the UK still has a long way to go before it can claim to be truly open and tolerant society. Its conclusion is that racial discrimination is still insidious and persistent.

Its key findings are that:

Overall, almost one in six respondents had experienced a racially motivated physical assault, but over a third of people identifying as Gypsy/Traveller, Roma or Other Black reported that they had been physically assaulted because of their ethnicity, race, colour, or religion.

More than a quarter had been verbally abused or insulted because of their ethnicity, race, colour or religion, and 17% reported experiencing damage to their personal property. Nearly a third reported racial discrimination in education and employment, and nearly a fifth reported racial discrimination when looking for housing.

Although the above findings can be interpreted as entirely negative, the good news is that it seems likely that some progress is being made, even though there is a long way to go. This is in spite of the UK going through a long period of uncertainty due to Brexit and austerity when it might have been expected that racial tensions would increase and racist groups would grow in prominence.

The far-right

It is now generally accepted and has been for some years that the far-right in the UK is weak and divided. There are numerous groups and new formations across the country but most of their activism is on line. Tommy Robinson for example has tried to mobilise support for racist projects, most recently against centres for asylum seekers, but these have generally been small and generally outmanoeuvred by left groups.According to Hope Not Hate, the levels of far-right activity have been low and mainly characterised by tactics such as leafletting, internet activity and banner drops, rather than boots on the ground. The racist positions of the Tory government on asylum seekers, and migrants do not seem to persuade the British people. Conspiracy theories abound of course and although, according to Hope Not Hate, many young men might express a positive attitude toward Andrew Tate, with over 50% having a positive attitude towards him, this is not born out in the overall data on racist attitudes or on the streets.

It also has to be acknowledged that some of the data cited in this piece, applies to England and Wales, rather than the entire UK and that there are particular issues in different parts of the UK, especially Northern Ireland and Scotland. Organisations, such as Stand Up to Racism, have done good work in combatting racism and political parties, such as the SWP and Socialist Party can take credit for confronting racists where-ever they meet them. It is often the case that the numbers of neo-fascist racists at eventsis very small and that engaging in discussion with those with confused and differing views on this subject, where it is safe to do so, can bear fruit. It is important, at least in England which is where I am experienced in such interventions, not to otherise people with differing views as automatically fascist or indeed racist. This characterisation was often attributed to those who sought to leave the European Union and those advocating this position were often otherised in this way. The data suggests, however that although people were not happy with being part of the EU and that there was a nationalist element to this, this did not make many of them overtly racist. According to Ipsos, the low numbers of people who agree with the statement, “In order to be truly British, you have to be white,” falling from 10% to 3% in the last 14 years would be one measure of a decline in racist attitudes, alongside others cited above.

The above picture of declining racist attitudes is in stark contrast with the increasingly racist outlook of the Conservative government as well as views expressed across the British media, with a press that is dominated by right-wing rhetoric. The UK has had a whole swathe of Prime Ministers and ministers, who espouse racist policies and opinions. The policy on refugees and asylum seekers and the attempt to export refugees from the UK to Rwanda for “processing”, which was passed by the UK Parliament on 18.01.2024, is one glaring example of a racist approach to refugees and asylum seekers, alongside many others. The racist rhetoric of people like Suella Braverman, the Home Secretary responsible devising for this policy, as well as the support of Johnson, Truss and Sunak, does not appear to have persuaded the majority of the British people that racism is acceptable and the policy has been strongly resisted by the civil service union (PCS). Even though many will be confused around individual issues, such as border controls, the deeper sentiment towards difference contradicts views that may be expressed on a specific issue. The paradox that the racism inherent in the British elite is not reflected in the consciousness of the British citizenry is certainly a conundrum. It would be of interest to see comparisons with other countries in Europe and beyond, where the far-right is clearly on the rise and represented in government. The finding of Focaldata, that “80% of Britons agree that the UK is a better place to live, as someone from an ethnic minority, than other countries like the USA, Germany or France,” shows at least a perception that things in the UK, while not perfect, are perceived as better than elsewhere.

Complex picture

Britain is certainly a multi-cultural society and the barriers between communities, although still quite marked in many places, are starting to diminish. There is a greater mixing of people from different cultural and racial groups across many parts of the UK. The assimilation of different foods, different art forms, especially popular music and different modes of speech into British culture may also be factors in diluting prejudice. As stated above, there is a long way to go. Racism is still a feature of institutionalised life as well as in the everyday experience of many. The progress that has been made since the 1980s, needs to be fought for and extended. The reasons for this progress are many and varied and there is need for detailed work to look at evidence behind these changes. Some of the obvious differences between the 1980s and even in the recent period can be seen through the visibility of people with difference, including people of colour across British advertising and in the media, as well as in prominent public positions. Advertising has been strikingly more diverse in this respect. This seems to suggest a perception that associating people of difference with advertised products will benefit the sale of those products. The BBC, although politically a puppet of the state, has given air time to numerous people of colour and championed liberal attitudes towards race for quite some years now. Following the fall of the Thatcher government in the 1980s, there was a trend towards more inclusivity. This was especially apparent in schools, where a zero tolerance of racism became the accepted approach and readily embraced by teachers. This does not of course suggest that issues around prejudice and racism were not still an issue, but that the determination of most teachers to improve the situation became more apparent.

The answer to the dilemma around why things appear to be improving and continue to improve in the UK is complex. Let’s celebrate the progress, campaign to keep the pressure on towards more progress and resist those who would seek to turn back the clock, such as, the right-wing press, far-right groups and The Conservative Party.The growth of the Reform Party, which emerged from UKIP (UK Independence Party) and the continued disproportionate promotion of its ideas, by the right-wing media, around the reduction of taxes, stronger policing, zero net immigration and reactionary social reform may get an echo with disaffected Conservative voters and some in disadvantaged communities. This happened during the Brexit period and could happen again, but as shown earlier, the support for Brexit, did not appear to have a corresponding long-term effect on social attitudes. Recent events in Israel / Palestine have also revealed a sinister trend within the Labour party. A look at the Labour Party constitution, reveals a clear definition of antisemitism for example, but not specifically other forms of prejudice, such as Islamophobia. Keir Starmer’s position on Gaza has revealed a one-sided support for Israel and a callous indifference to the plight of the Palestinians. In his radio interview on LBC, this was absolutely clear, when he gave carte blanche to the Israelis to use whatever force they wanted in blockading Gaza. Starmer’s rhetorical support forneo-liberalism, patriotism and the royal family also shows a reactionary trait. These traits could combine and have a wider negative influence. Indeed, it will be interesting to examine next years’hate crime statistics. The presence of Muslims in great numbers on street protests in support of the Palestinians and their turning against Labour politicians who refuse to back a ceasefire is striking. They are uniting with pro-Palestinian activists, but are also interpreting the position of the Labour leadership asIslamophobic. At the same time, there are those who support the attacks on Palestine and although they are not particularly visible at the moment, they could gain confidence over time if the entire British elite, including the Labour Party continues with its support for the war crimes being carried out by Israel in Gaza and elsewhere in the region.

In conclusion

In conclusion, I would argue that overall, there is some evidence to support the notion that most forms of prejudice, including racism, are declining in the UK. While this is welcome, it does not in any sense mean that the UK is a society free from racism and intolerance. There is a long way to go and the ground that has been won on this issue could be lost if racist attitudes are expressed by wider sections of the community. This is why I mention Keir Starmer’s worrying pronouncements on Gaza, and his generally imperialistic approach to events in the Middle East. These could find an echo across supporters of the Labour Party leading into elections. As it seems likely that the next UK government will be a Labour government, those within the Labour Party and outside, need to stand against Starmer’s slide into jingoism, neo-liberalism, imperialism and ultimately, racism.

The likely rise of the Reform Party will also mean that the opportunity for the Left to put across its message will shrink still further, following the brief flowering of discourse during the Corbyn period and the climate strikes. The remorseless consequence of right-wing ideas being thrust into the political arena to an even greater extent than previously could lead to a perfidious erosion of the gains made. A Labour government that imposes austerity on the people, will also drive people away from progressive ideas and toward reactionary ones, especially in a situation where the voice of the Left is not given any air-time. The clear neo-liberal approach of the next Labour government is likely to mean that disillusion with what might at one time have seemed a progressive party will be completed and a right-wing reaction is likely to follow.

The grinding pessimism of many on the Left should not however dominate the discourse and lead to despair and a moving away from political struggle. The idea that long-term attitudes to race and difference are deteriorating is simply not there at the present time, according to the research presented above and every-day experience. The positive trends, should give the Left a signal that by uniting in action it can help produce more positive developments. It should also remind it that within the Trades Unions and the Labour Party there had been a broadly positive perspective towards people of difference, which has contributed in no small way to these gains. This is still the case within trade unions except around transgenderism, where the PCS (Civil service union) was riven with disagreement over its approach. The worry is that such rifts grow and that the right-wing shift of the Labour Party allows increasing levels of reactionary ideas to flourish. The growing support for right-wing forces, following the betrayals of the social democratic parties across Europe and elsewhere, is ample evidence that the UK faces a palpable threat to the gains made on attitudes to race and difference in the next few years.

The current situation in Gaza is being thrust forward as a contentious issue in the UK, when it could have been a cause for unity. If the Labour Party had taken a humanitarian stance alongside the SDP, Greens and even the Lib Dems, the significant rise in incidents of Islamophobia reported by Tell Mama since 07.10.24 at over 700% and antisemitism reported by the Common Security Trust at 589% may have been lower. It shows the racist positions of the British government and the Labour Party being reflected on the streets. So, the previously improving picture is now under threat. The Tory media and Conservative politicians are also trying to stoke up racial tension by portraying the legitimate protests of many Muslims and other supporters of the Palestinian cause as a threat to democracy and the “British way of life”. In a recent poll by Hope Not Hate, 35% of those surveyed thought that the Islamification of British culture was a greater threat than immigration with over 20 % of Labour voters believing this to be the case.The victory of George Galloway in the Parliamentary bye-election on 29th February however, suggests a willingness from voters to support a Left alternative candidate, who clearly confronts Labour on the issue of Gaza and who they see as having a chance of winning.

Unity on the Left has won gains in the past, but this unity needs to be strengthened quickly and dynamically in order to forestall a slide backwards into reaction. The old adage from many in the Labour Party, that you can’t change it from the outside is not coherent. The Labour Party is now a fully realised neo-liberal party and the Left has not the power to change it and will not be allowed to access such power. The threat to gains made around inclusivity, is one highly significant reason, alongside many others, why it is more important than ever to build a credible political alternative to the Labour Party and build it quickly.