January 4th-5th marks the 50th anniversary of a 24-hour period which saw some of the most horrific killings of the “Troubles” in Northern Ireland. Sixteen men-six Catholics and ten Protestants-died in three gun attacks in South Armagh. This slaughter was the culmination of months of sectarian violence which had cost hundreds of lives. The North held its collective breath and waited for more: all out civil war was a real possibility. Instead, the horrors of January 4th-5th were answered by united workers protests demanding an end to the violence.

A Spiral of Violence

County Armagh had been convulsed by sectarian killings in the previous six months. On July 31st, loyalist paramilitaries shot five members of the Miami Showband killing three, after stopping their minibus at a fake military checkpoint. On September 1st the IRA attacked Tullyvallan Orange Hall killing five Protestant civilians. The attack was claimed by a group calling itself the “South Armagh Republican Action Force” but everyone knew the IRA were behind it. On December 19th two Catholics were killed when a car bomb exploded outside a pub in Dundalk, just across the border in the Republic of Ireland, and three more Catholics were killed in a gun and bomb attack on a pub in Silverbridge. The Loyalist attacks involved both paramilitaries and serving members of the state forces (police and locally recruited British army units)-what became known as the “Glenanne gang” were involved in the killings of many dozens of people.

The grim year of 1975 ended with the death of three Protestants who were killed in a bomb attack on a pub in Gilford on December 31st. The “People’s Republican Army” claimed responsibility but in this case the actual perpetrators were the Irish National Liberation Army.

All expectations were for more bloodletting in 1976, and further savage violence was not long in coming. On the evening of January 5th, six Catholics-three Reavey brothers and three members of the O’Dowd family – were killed in two separate attacks on their homes by the loyalist paramilitary Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF). One day later, the IRA retaliated, again using the cover name of the South Armagh Republican Action Force. They stopped a bus taking factory workers home on a country road near Kingsmill. They asked all the 12 men on the bus their religion. There were 11 Protestants on board and fearing that the gunmen were about to kill the only Catholic, they tried to protect him. Instead, it was the Protestants who were the targets and they were mown down with rifle fire before being finished off with revolver shots to the head. Ten died whilst one miraculously escaped with 18 separate bullet wounds and lived to tell the tale of what became known as the “Kingsmill massacre”.

United Workers Response

Members of Militant, then organised with others in the Labour and Trade Union Group, had already been raising the call for united workers action to challenge the paramilitaries for many months. Action had been taken in December 1975 when the IRA shot dead two Protestant businessmen who were sitting in a cafe in the centre of Derry. The local Trades Union Council called a strike and demonstration, and 5,000 workers turned out to register their disgust.

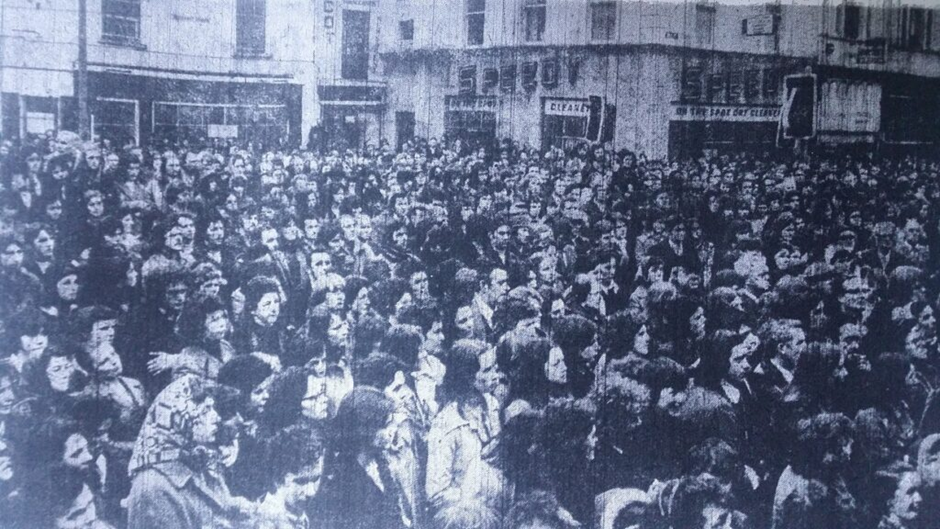

After the Reavey/O’Dowd murders and the Kingsmill massacre, the Trades Council in the nearby town of Newry immediately called a strike which closed most of the factories and workplaces of the town and brought thousands onto the streets. In the Lurgan-Portadown area, where no Trades Council had existed for nearly thirty years, shop stewards from the largest local employer, the huge Goodyear tyre factory, took the initiative, coming together with other shop stewards to call a strike. Seven thousand workers marched in Lurgan. These three regional strikes and demonstrations were the first generalised response from the workers movement for several years.

Right across Northern Ireland, the pressure began to mount on the trade union leaders to follow the examples set by Derry, Newry and Lurgan. Had the Irish Congress of Trade Unions – the leadership of the union movement – reacted quickly and called a one-day strike of all workers, the response would have been overwhelming. It would have tapped the mood of anger at the killings and also given the working class a sense of their power.

Instead, in the weeks and months that followed the Irish Congress of Trade Unions (ICTU), under pressure from the rank and file, simply organised the “Better Life for All Campaign”. The highlight of the Campaign was a two-minute silence in memory of all the victims of the Troubles in late January. It was widely supported as workers across the North stopped work. Unfortunately, ICTU did little more. The Campaign did not develop the dynamism and confidence that was necessary despite the efforts of Militant supporters who argued that it should take up the class issues of poverty and unemployment which were feeding the violence, robustly oppose sectarianism, and take up the issue of state repression. The weakness of the response of the official movement meant that later in 1976, the “Peace People”, a cross-class movement against the violence, provided an outlet for the intense yearning for peace in working-class areas.

In the summer and autumn a series of rallies were held across the North. 20,000 turned out at Belfast’s Ormeau Park, 30,000 on the Shankill Road Belfast, 25,000 in Derry and many thousands more in Antrim, Coleraine, Strabane, Craigavon, Dungannon, Newtownards, Ballynahinch and elsewhere.

The workers movement cannot and should not forget the events of 50 years ago. The role of the Glenanne gang remains to be fully exposed. So too the sectarian actions of the IRA who carried out the Kingsmill massacre, an act it has denied ever since. And we must learn the most important lesson: it is only the workers’ movement which is capable of really challenging sectarianism, and the system which creates poverty and division. The system of capitalism.