This is the second part of a series of articles. Read the introduction here and part I here

Introduction

From the first days Militant in Ireland was focused on the need to recruit women workers and especially young women. This focus was reflected in all of our work on a day-to-day basis. In the months when we were organising against the fascist National Front (see Fighting Oppression, Part One) we were also taking up issues relating to the special oppression of women. Indeed, when our paper reported back on the events in Coleraine it also reported that comrades had successfully moved a motion at the conference of Northern Ireland’s largest union, the Northern Ireland Public Service Alliance (NIPSA) calling for strong countermeasures against the sexual harassment of women. In the same issue, we also had a prominent focus on the strip searching of women prisoners (mostly IRA members) in Armagh jail. Repression and jail conditions were very important issues in this period, and only Militant supporters had a track record of raising these issues in the wider workers’ movement in a manner which was not divisive.

Campaigning Against Strip Searching of Women Prisoners

In the July/August 1984 issue of Militant Irish Monthly we published an article headlined “Stop Armagh Strip Searches” and printed in its entirety a letter smuggled out of Armagh woman’s prison, which, as it said, “clearly exposes the intentions behind strip searches and the inhuman way in which they conducted”. [1]

Our covering article stated “repression in Northern Ireland must be taken up by the labour and trade union movement, measures used today against paramilitary groupings will be perfected for future use against the organizations of the working class. The brutal police tactics used in the miners’ dispute showed us all too clearly, only the labour movement by struggling to unite working people around socialist policies can solve the problems of the North. Reliance on the state or turning a blind eye to repression, solves nothing and prepares the way for measures against trade unionists and socialists in the future. Militant is absolutely opposed to the barbarous strip searches inflicted on prisoners in the North. This owes nothing to security and everything to an attempt to break the morale and dignity of the prisoners”. [2]

In the 1970s and 1980s prisoners often smuggled letters out of prisons, usually concealed in the bodies of visitors. The letter from within the prison is stark in its description of the brutality of the prison regime, and the special oppression of women prisoners, in a deliberate attempt to break their spirits:

“Strip searching has been an ongoing practice here in Armagh since November 1982… A strip search is enforced upon all prisoners leaving or re-entering the prison by screws [prisoner officers] assigned to the duty. The prisoner is ordered to strip completely naked. Each item of clothing removed is immediately taken away by one of the screws present to be examined. The prisoner must then remain standing in full view of the screws (four or more) while a visual frontal and rear inspection of her person is performed. The woman is ordered to turn a number of times before clothes are returned and she is permitted to dress again.

It continued: “Should a woman be in the menstrual state she is compelled to remove pants and the sanitary towel and stand exposed and protected until the visual inspections be completed. The same conditions are imposed on pregnant women…”

Prisoners on trial in a nearby courthouse “bore the brunt of this measure. Weekly they have been compelled to comply to the regulation before and after their court appearances in Armagh courthouse which stands a mere 200 yards from the prison, and which involves no more than a 15-minute absence from the jail”.

The prisoners argued “The strip search procedure is a nightmarish ordeal with profound psychological undertones… primarily strip searches were not securely motivated”.

In 1983 there were 1218 strip searches in Armagh, compared to only 50 in all female prisons in England, Scotland and Wales.Militant recognized that this was not only an issue of repression, but one that is specifically directed against women and its brutal nature needed to be opposed. We raised strip searching and other repressive measures in the trade unions and were successful in winning union conference votes on issues with the potential to cause division as violence continued.

“Women Are a Doubly Oppressed Section of Society”

We sought to raise the consciousness of comrades regarding the necessity to take special steps to involve women, especially young women, in our work. When Militant agreed the text of a “Northern Perspectives” document at our 1984 conference, we outlined how:

“The coming revolutionary storms internationally, and the unfolding of the class movement in Northern Ireland, will provide enormous opportunities for the development of Marxist ideas. Women are a doubly oppressed section of society. In every major struggle in recent years women have played a vital role. This was the case, for example, during the 1982 health strike. Through involvement in bitter class struggle the consciousness of this section of the class will be raised and wider layers of working-class women will come to the ideas of Marxism”.

We drew attention to the radicalising effect of the miners’ strike, then in its third month:

“The role of the miners’ wives in the dispute in Britain has given a breath-taking demonstration of the élan, determination, and inventiveness of working-class women as they become involved in struggle. This has been the biggest movement of women since the war. Miners’ wives have been to the forefront on the picket lines, organising collections, and on demonstrations. Women whose former horizons were limited by their domestic tasks have been politicised and many have found their way to Marxist ideas. This dispute is a foretaste of what is to come. Already women in Northern Ireland have a tradition of struggle. In local struggles they have often played the leading role. The tendency in coming years will be for working class women to become involved in industrial, community and political activity”.

We concluded that:

“Women are an important part of the Northern Ireland workforce… The penetration of Marxist ideas among this layer of the proletariat is a critical aspect of the development of Marxism in Northern Ireland. There can be no successful Marxist newspaper unless it is capable of drawing its readership and support from male and female workers alike”.[3]

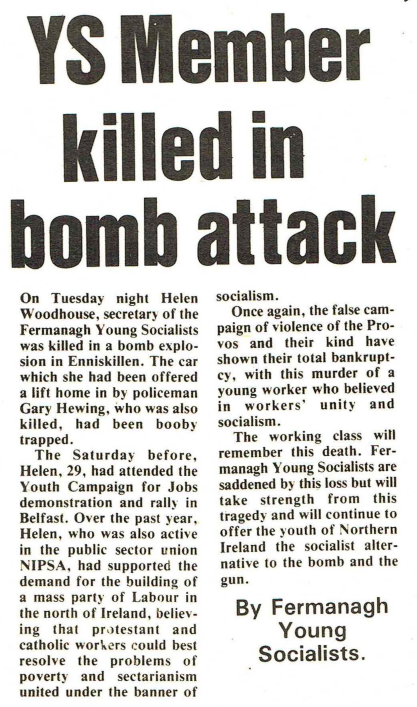

One of the young women who was drawn to our ideas in this period was Helen Woodhouse, from Enniskillen, County Fermanagh and Protestant by background. She worked in the Lakeland Leisure Centre, was an activist in the trade union NIPSA, and was secretary of Fermanagh Young Socialists. Helen died on November 9th, 1982, when a booby trap bomb exploded under the car of police officer Gary Ewing who had offered her a lift home from work, and who also died. Days before she had taken part in a march against youth unemployment organised by the Young Socialists in Belfast which saw 500 Catholic and Protestant young people and trade unionists demonstrate side by side.

“Reclaim the Night” and Abortion Rights

The 1984 conference statement is focused on what might be termed “class issues” rather than issues of special oppression, but we also took up issues that affected women specifically.

Militant members intervened in the women’s movement from in the 1970s onwards. Comrades were on the 1987 “Reclaim the Night” march, which proceeded from Stranmillis College, and past Queen’s University to Belfast City Hall. Over a long period, we were fighting to win the extension of the 1967 Abortion Act to Northern Ireland (the 1967 made abortion available in England, Scotland and Wales).

Raising the issue of abortion rights was difficult at the time. The Northern Ireland Women’s Rights Movement was established by a group of students at Queen’s University in 1975. Many of its core members were either members of or associated with the Communist Party of Ireland. They did not focus on issues relating to reproductive rights, especially abortion, as they calculated that the risk of shattering the unity of women’s movement was too high.

From 1975 we worked with many others in the Labour and Trade Union Group (LTUG), a broader formation we initiated when the Northern Ireland Labour Party collapsed. We sought to build a broader youth organization through the Young Socialists from 1979. The LTUG and Young Socialists held joint conferences in 1980, 1981 and 1982 and at these events the question of abortion rights was debated and discussed. Motions were passed in favour of the extension of the 1967 Abortion Act and we took the struggle for abortion rights into a number of unions in this period.

The public sector union NIPSA, in which comrades played an important role, became one of the first unions to adopt this policy, through our efforts. The union annual conference position see-sawed back and forwards over several years as “pro-life” forces mobilised to overturn each vote in favour of abortion rights before a settled position was arrived at. We were also the reason why NIPSA became the first union in Northern Ireland to organise a crèche at its conference to ensure women could fully participate.

A decade later, in a Militant Student Bulletin, we noted attacks on student unions during 1988 and 1989 from the Society for the Protection of the Unborn Child (SPUC).[8] Student leaders from University College Dublin (UCD) had been instructed by the courts to pay legal costs of £50,000 pounds after a case taken by SPUC to stop student unions from providing information on abortion was referred to the European Court.

The Bulletin stated, “Militant believes that USI and student unions with a pro-Information policy, should continue to distribute the information. Right to information groups should be set up in all colleges where the Union does not have a pro-information policy to campaign for a change in Union policy. We call for a national convention to be held in the next year of all pro-information student unions and all right to information groups to review the work and plan campaigns for the next period of time”.

We went on, “as well as fighting to stop SPUC’s attempts to turn back the clock, Militant supporters campaign for a massive extension of civil rights in this area. We stand for Sex Education in all schools; freely available contraception; the introduction of civil divorce; repeal of the 1983 constitutional amendment; the Right to Information; reopen the clinics; women’s right to control their own bodies, including the right to safe abortion facilities provided by the Irish health service”.

The article noted that at least 4,000 Irish women were traveling to Britain for abortions annually. The campaigning work of the students’ unions had involved more than 40,000 students in meetings and referenda on the issue who had voted by 33,000 to 11,000 for the right to information. We argued that “sometimes it is necessary to break an unjust law” and we called on the student unions to “break the law rather than deny information to women who needed it very badly”.

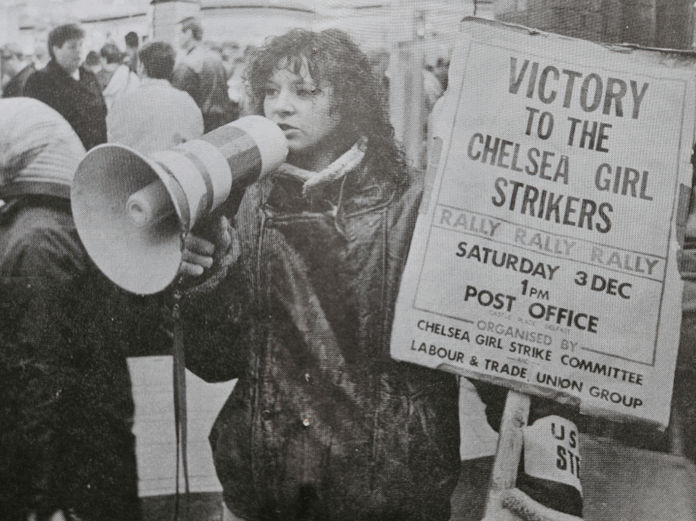

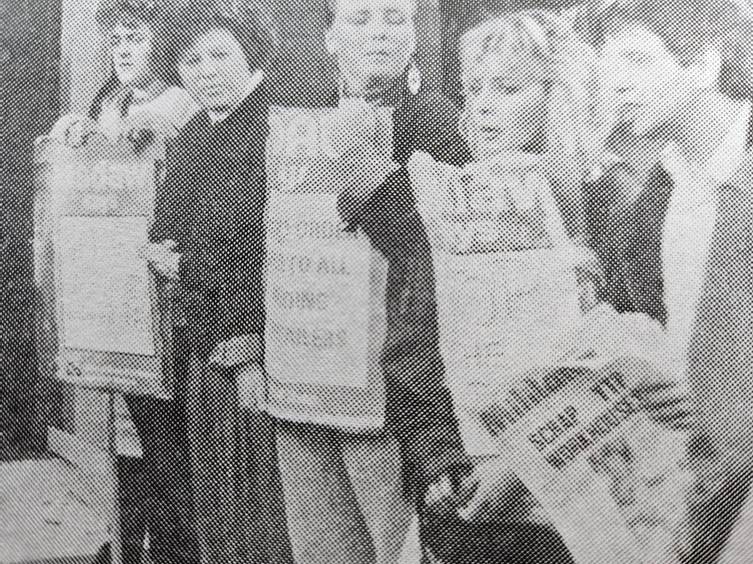

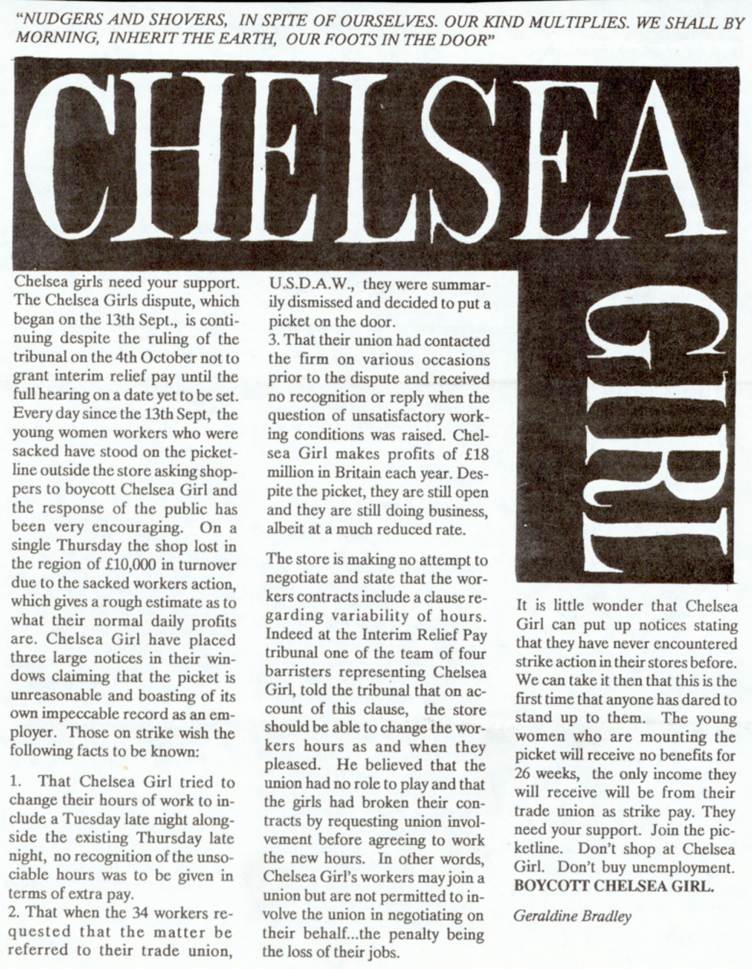

Supporting Young Women on Strike: the Chelsea Girl Dispute

In September 1988 34 young women workers went on strike at the Chelsea Girl clothes shop in the centre of Belfast. Militant comrades intervened on the first day and worked with the strikers over the following months to assist them in their efforts for dignity and justice. We were very mindful of the fact that the workers, in this case, members of the Union of Shop and Allied and Distributive Workers, were young and female, and we were determined to stand by their side. We put all the resources of the party at their disposal. Their heroic fight stands alongside other historic battles in Northern Ireland’s labour history.

The Labour and Trade Union Group and Young Socialists and the strike committee worked together in lockstep. Rank and file trade unionists joined the strikers regularly. The NI Women’s Rights Movement joined the picket line, and the women’s movement press covered the events. In the early days of the dispute, we argued that pickets should be put on other Chelsea Girl shops in Northern Ireland and England, Scotland and Wales, and Militant members in England, Scotland and Wales worked to make this happen.

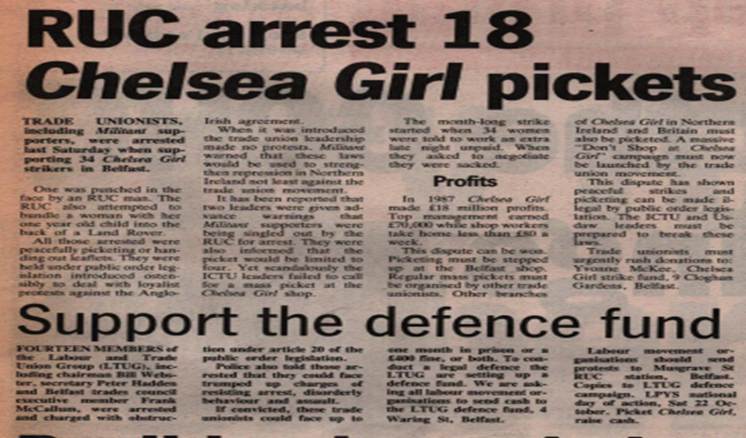

During this dispute the strikers faced the full force of Tory laws, court injunctions, arrests and harassment from the police (Royal Ulster Constabulary-RUC) yet they refused to yield.[9] The State employed aggressive tactics from day one. On Saturday, October 25th, 18 pickets were arrested outside Chelsea girl (14 Militant members and 4 others). Those arrested included the chair of the Labour Trade Union Group, Bill Webster, LTUG Secretary Peter Haddon and Belfast Trades Council Executive member Frank McCallan. The pickets were charged with obstruction, and attempts were made to limit the number of pickets to six or less, in line with Tory anti-trade union legislation.

Before the arrests, leaders of the Irish Congress of Trade Unions had been told by the police that Militant supporters would be arrested, but they did nothing to sound a warning. In fact, the local trade union bureaucracy were seen to point out comrades who were arrested. One comrade was punched in the face by an RUC officer. The RUC also attempted to bundle a woman with a one-year-old child into the back of a Land Rover. Those arrested were held under public order legislation, which had been introduced several years earlier to deal with loyalist protests against the Anglo-Irish Agreement. When the legislation was introduced, Militant warned that repressive legislation would be used against the trade union movement in time.

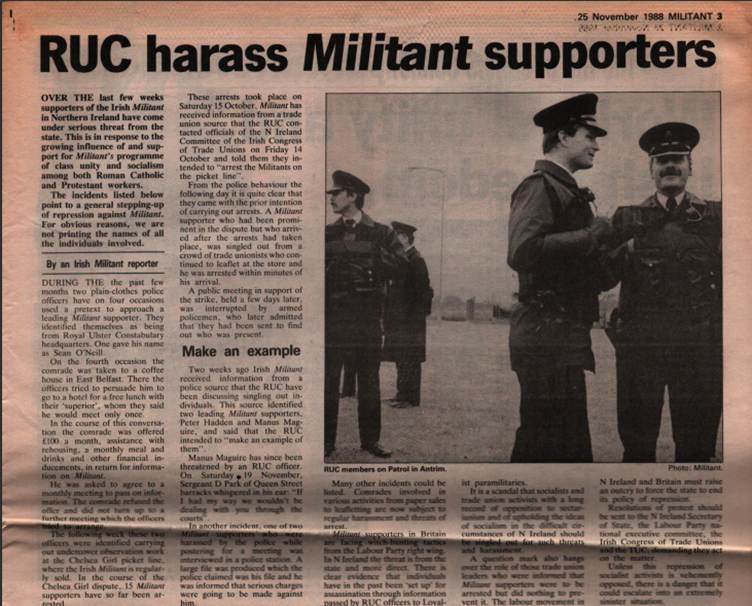

On the 25th of November 1988 we reported on the harassment of Militant members. One comrade had been approached by plain clothes police officers on four separate occasions who offered him £100 a month, assistance with rehousing and a monthly meal and drinks allowance in return for information on Militant. A public meeting we organized in support of the strike was interrupted by armed policemen who later admitted that they had been sent to find out who was present. We were informed that two leading comrades, Peter Hadden and Manus Maguire, had been specifically targeted by the RUC, who intended to “make an example” of them. Manus Maguire was threatened on Saturday 19th November, when a police sergeant whispered in his ear, “If I had my way, we wouldn’t be dealing with you through the courts”. We were not just fighting an industrial dispute against vicious employers seeking to super-exploit young female workers but were fighting repressive actions aimed squarely at socialist and treat union activists.

We have a long track record of standing by workers on strike, and not just dipping in and out of disputes, as is the tendency of some left groups. We recruited three of the leaders of the strike to Militant, a further demonstration of our willingness and ability to work with young female class fighters. We later explained the conduct of the dispute in a pamphlet and explained how a tremendous outright victory could have been achieved. Break the Chain, the story of the Chelsea Girl Strike was published in conjunction with the strike committee.[13]

Women Workers in Struggle: Childcare, Term time Workers and Classroom Assistants

In the first years of the new century, we engaged in further groundbreaking trade union work with groups of workers who were almost all women-childcare workers and term time workers in 2000, and classroom assistants in 2008. We do not have space to explain all of these disputes here but will instead concentrate on one-the historic term time workers’ dispute.

It began when one term time worker brought a complaint about not being paid for school holiday periods to the branch officers of the South Eastern Education and Library Board branch of NIPSA. The officers, members of the Socialist Party, took the issue up. Term time workers were consulted and came up with a claim for the payment of a retainer fee to cover holiday periods.

This led to a protracted and a bitter dispute involving regular protests, lobbies, pickets and demonstrations all of which attracted considerable press attention. The dispute spread across the five Education and Library Boards, but the epicentre was the South Eastern Board where the Socialist Party led NIPSA branch was strongest. Many term time workers had not even considered joining a union let alone going on strike before but when they at last saw the union doing something there was a flood of recruits. This was especially so in the South Eastern Beard where there was the strongest leadership. By the end of the dispute the South Eastern NIPSA branch had more term time workers than the other four Boards put together.

Demands for a ballot were initially turned down by the NIPSA leadership. Instead, senior NIPSA officials, along with officials from UNISON and other unions conducted secret negotiations with the Education Department, lead then by Sinn Fein minister Martin McGuinness. Behind the backs of the term time workers and their representatives they agreed a “deal” – that the workers should accept their existing salary spread over twelve months.

Only a massive campaign within the union and among term time workers in all Boards, spearheaded by Socialist Party members, prevented this agreement going through and forced the union to ballot term time members on it. The result was a shattering rejection – across the whole of Northern Ireland only one person voted to accept the deal. This was a turning point in the dispute. The term time workers had become a cause celebre in NIPSA. Other branches rallied behind them against the union leadership. The June 2000 NIPSA conference was dominated by the dispute and the call for a strike ballot could no longer be resisted. Faced with the certainty that a ballot would result in a resounding “yes” for a strike that would close schools and cause a major crisis for the Assembly the employers capitulated.

We argued afterwards that: “This was a huge victory achieved by a group of workers with no history of industrial militancy and scattered across dozens of workplaces. It was a victory that was only possible because Socialist Party members at the hub of the dispute in the South Eastern Board area were able to provide the direction that was needed”.

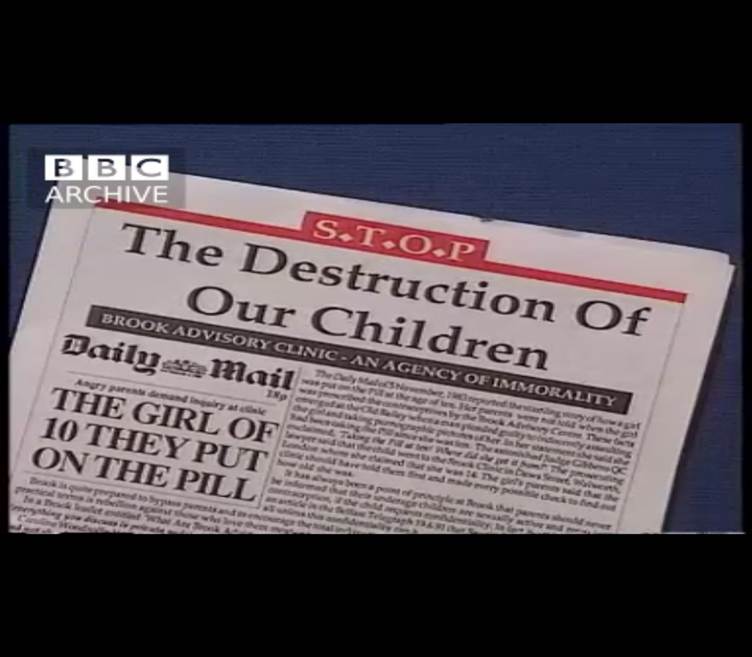

Defending the Brook Advisory Centre

On September 19th, 1992, the Brook Advisory Centre opened a clinic in central Belfast. The Brook Centres were developed in England from 1964 by radical health campaigners and women’s rights activists linked to the Marie Stopes organisation, to provide access to contraceptive care for young and unmarried people, especially in more deprived areas.[14] [15] One of the first centres was in Bristol, and it met fierce local opposition in the 1960s. In the 1970s the right-wing press ran scare stories about the activities of Brook, but by the late 1980s it had become an accepted part of the English reproductive health care system.

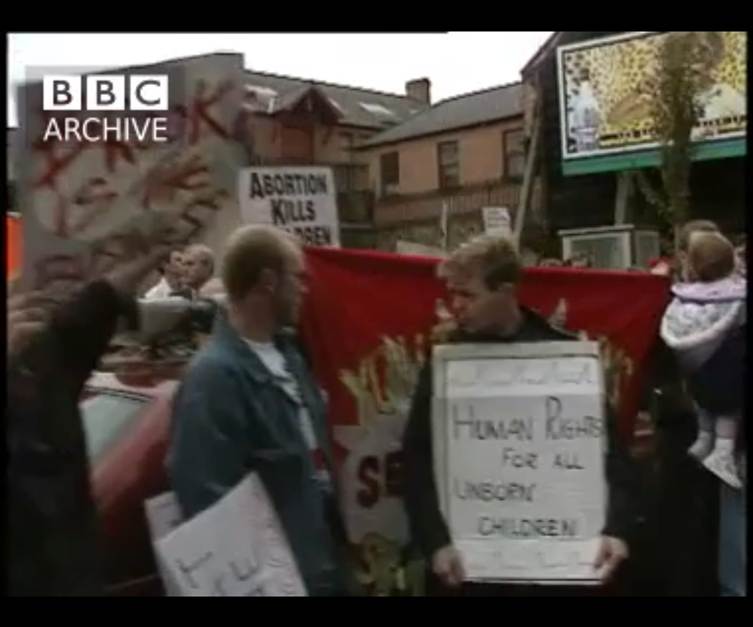

When Brook was invited to Belfast in 1992 there was a wall of opposition from both sides of the sectarian divide. On the night it opened, there was a large and noisy demonstration outside organised by reactionary elements including both SPUC (which was Catholic church aligned) and the Free Presbyterian Church (lead by Ian Paisley of the Democratic Unionist Party), but one young woman braved this and walked through its door.

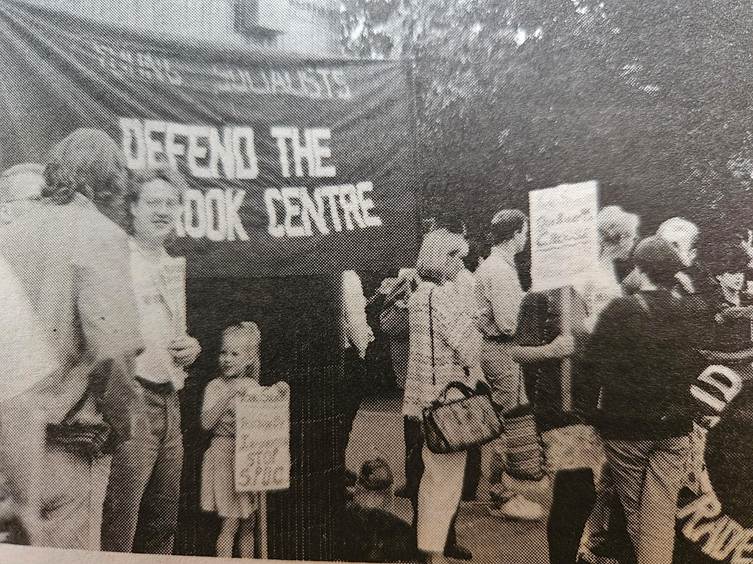

From that first night, Belfast Trades Union Council, left groups, and women’s groups mobilised a counter demonstration to the bigots. From then until the middle of the following year, the most consistent and persistent counter-protesters were the Young Socialists and Militant members. In our leaflets and paper, we drew attention to the class dimension of the struggle for improved reproductive health care. We raised the issue of support for the establishment of the Brook Centre in the trade unions.

The opposition were united in their backward ideas but could not stand together on the street. This resulted in two separate protests, on different days of the week, one led by Ian Paisley and his acolytes, and the other by ultra-conservative SDLP (Social Democratic and Labour Party-the main nationalist party at the time, with a largely Catholic vote) politician and future Lord Mayor of Belfast Alban McGuinness.

We were there every Thursday evening and Saturday (the Centre had limited opening hours-we were there when it was open), without fail, and for many months. Comrades travelled from the branches outside Belfast to participate. When others began to fall away, we argued that the protest needed to be maintained until the reactionaries on the other side of the street had lost heart. Our view was that it was necessary to protect the young women, and young men, who were seeking to use the service until it was firmly established. We drew this conclusion, and acted accordingly, even though it was not the most fruitful arena for gaining recruits at the time.

As part of our campaigning work, we issued a leaflet and petition entitled “Campaign for a Brook Advice Centre in Belfast” under the name of the Young Socialists. In it, we stated “ask your friends and workmates to send a letter and get involved in the campaign. If you’re in an organisation, for example, the trade union branch or youth club asks them to lend support too. If you need more model letters, information or even a speaker, get in touch with us or the Belfast Brook Advisory Centre Steering Group”.

Our model letter further stated, “we welcome the opening of a Brook Advice Centre in Belfast in order to provide general counselling and informal advice to youth and others on contraception. We condemn the campaign launched by SPUC and other organizations, including most of the main political parties, to try and prevent this vital step forward”. We finished “the Brook service is essential, especially for youth. Advice on safe sex must be available without harassment”.

Just days after the first counter-protest outside Brook the IRA exploded a 3000 lb bomb (one of the largest ever in the Troubles) at the Northern Ireland Forensic Science Laboratory in South Belfast. The laboratory was obliterated, and seven hundred houses were damaged and 50 people injured in the Protestant Belvoir housing estate across the road. Such actions always caused an increase in sectarian tension and did so on this occasion. Four miles away we maintained our protests, in opposition to the very sectarian politicians who sustained the violence. We understood that there was a complex interplay of forces at work, and our opposition to both unionism and nationalism, including to their reactionary positions on social issues was vitally important.

We saw them off. The Brook Centre survived and in time its services were subsumed by a different organisation, and it still exists today. It allowed easy access to advice and contraception and indirect access to safe terminations, both locally and through facilitating the travel of women to Great Britain.

Soon after the Brook defence campaign the Campaign Against Domestic Violence (CADV) was launched. It was initiated by comrades in Britain and was focused on activity in the wider labour movement, especially the trade unions. We adopted the campaign in the North. CADV material was available at all branch meetings and comrades were expected to take it with them into their activities, at a time when all comrades in work were active in their local union branch or other union structures. We maintained our presence on Reclaim the Streets marches, and in the same period we carried material in our paper on women’s rights issues, including an interview with the director of the Belfast Rape Crisis Centre.

Everything in Context: Objective and Subjective Factors

It is not possible to explain our past campaigns without establishing the context. In the case of the defence of the Brook Centre we need to set this work against the objective conditions in the early 1990s, the other work we engaged in, and the “subjective factor”, that is the internal life of the Militant at the time.

In the 1970s, 1980s and into the 1990s we were focused primarily on the need to defend and build workers’ unity, and counter sectarian ideas and politics, sectarian threats and sectarian violence.[19] In the early 1990s we were under considerable pressure internally. The party was not growing in the aftermath of the sectarian upsurge after the Anglo-Irish Agreement in 1985, the defeat of the Great Miners’ Strike, also in 1985, and the collapse of the Soviet Union and the other deformed worker states in 1989 and 1990. Loyalist paramilitaries were engaged in a fierce campaign of terror, which left dozens of dead as sectarian massacres occurred with a frequency not seen since the 1970s. The IRA had broadened its concept of legitimate targets to bring in a huge swathe of the Protestant population and were cutting down building workers and contractors who maintained army and police bases.

The campaign in defence of Brook took place in a period when the threat of sectarian assassination once again haunted working-class communities. In the five years from 1989 to1994 we were central to the physical and political opposition to the sectarian elements who were consciously or unconsciously dragging the North in the direction of civil war. We lead by example when on March 9th, 1989, we organised the first area-wide strike against sectarian killings since January 1976, in Magherafelt and Cookstown. In January 1992 a second strike in the area brought out thousands after the IRA killed eight Protestant building workers and maiming six others in a roadside bomb at Teebane.

We took our ideas to a wider audience by standing in two constituencies in the April 1992 General Election. In South Belfast we gained one of our best ever results, and in Mid-Ulster constituency, scene of the Teebane massacre and protests, we won a credible vote in a highly polarised atmosphere. We stood again in the May 1993 Local Elections, in three areas. We also travelled across the border to assist the comrades in Dublin West who were on the threshold of our first electoral success.

It was at this time that we were initiating our “open turn”, which lead to the formation of Militant Labour and then the Socialist Party. We were also engaged in a process of discussion around our position on the national question which resulted in an important clarification of our ideas and the publication of several landmark pamphlets.

We sought to maintain a balanced approach to our work, mindful of our slender resources, and the immense responsibilities on our shoulders. These were dangerous and difficult times, and we had to devote much of our efforts to the defence of workers unity and workers lives. The strikes organised by comrades put down a marker for the rest of the movement and took considerable courage. It goes without saying that the same comrades who were active in the unions, and who risked their lives countering sectarianism, were regular participants on the defend the Brook Centre protests.

[1] Militant Irish Monthly, July/August 1984.

[2] Militant Irish Monthly, July/August 1984.

[3] The document was later published asNorthern Ireland: A Marxist analysis (August 1984) https://www.marxists.org/history/etol/writers/hadden/1984/08/analysis.html

[4] Lost Lives: The stories of the men women and children who died as a result of the Northern Ireland troubles. David McKittrick, Seamus Kelters, Brain Feeney, Chis Thornton and David McVea. Mainstream Publishing, Edinburgh and London, 2012: Her father was an ambulance driver at the local hospital and was quoted as saying “its terrible when it happens to one of your own family. Thank God I wasn’t on duty last night because it would have been awful if I had been sent to the scene and discovered it was my own daughter”.

[5] Photograph South East Fermanagh Foundation (SEFF) website.

[6] Militant no 626, November 12th, 1982.

[7] BBC Archive

[8] Militant Student Bulletin, 1990.

[9] Breaking the Chain. Chelsea Girl Strike Committee, Labour and Trade Union Group, 1989.

[10] Women Write, October / November 1988.

[11] Militant no 918, October 21st, 1988.

[12] Militant no 923, November 25th, 1988.

[13] Chelsea Girl Breaking the Chain: Chelsea Girl Strike Committee and Labour and Trade Union Group, 1989.

[14] https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-british-studies/article/youth-sexuality-responsibility-and-the-opening-of-the-brook-advisory-centres-in-london-and-birmingham-in-the-1960s/3EADDAD906AB433270DE6EA534167646

[15] Responsible Pleasure. The Brook Advisory Centres and Youth Sexuality in Postwar Britain

Caroline Rusterholz. Oxford (UK): Oxford University Press; 2024 May.

[16] BBC Archive

[17] BBC Archive.

[18] BBC Archive

[19] When workers stood united Striking against sectarianism. Michael Cleary, Socialism Today, Issue 188 May 2015. http://socialismtoday.org/archive/188/nireland.html