This is the first part of a series of articles. Read the introduction here

Fascism represents the gravest threat to the organised workers movement, to the safety of people of colour, LGBTQ+ people, and to the rights of women. Socialists must challenge fascism whenever it rears its head. In his account of 75 years of the many fascist attempts to develop a base in Northern Ireland researcher James Loughlin describes two occasions only when they were successfully physically and politically confronted: the “Labour Movement Campaign Against Fascism” counter-protest against the National Front in Coleraine in 1984, and the “Fascists Out Campaign” physical confrontation with the White Nationalist Party in Portrush in 2004.[1] Twice they were stopped. And twice the Militant/Socialist Party was central to this success.

Here we give an account of the events of 1984. A second article will describe the defeat of the White Nationalist Party twenty years later.

The National Front: A Nazi Front

In September 1983 the fascist National Front (NF) marched from the Shankill Road to Belfast city centre with the intention of confronting a Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament rally. There had been little publicity before this march, and it appears the police and military were taken unawares. Comrades in Militant and the Young Socialists had no time to prepare a counter demonstration on that Saturday. We were not in the city centre but were engaged in activity elsewhere and learned of the demonstration through the press the following day.

The march went down as a significant if secondary moment in the history of the Troubles, because it was on this day that a group of young loyalists who were to become notorious in the coming years first stepped on to the public stage. Participants in the march and active members of the National Front were Johnny Adair, later to be leader of the vicious C Company of the Ulster Defence Association/Ulster Freedom Fighters on the Shankill Road, and his associates Sam McCrory, Jacky Thompson and Donald Hodgen. Together they were responsible for the deaths of up to 50 people in the 1990s and 2000s.[2]

We discussed the issue and immediately sought evidence of ongoing National Front activity anywhere in Northern Ireland. The National Front had been trying to establish a base in Northern Ireland for a decade and had previously marched on the Shankill Road in 1973 (see photo). In August 1979, Loughlin reports, “contacts were established between the Belfast National Front and the remains of Tara, one of the North’s most sinister loyalist paramilitary groups, most of whom were youthful, chiefly in East Belfast”[3]. Also, according to Loughlin, the National Front protested at the United States consulate in Belfast against the American government’s refusal to sell firearms to the RUC in February 1980[4]. Whether this protest went ahead is unclear: we reported in the Militant newspaper in 1984 that the protest had been called off because of the threat of a trade union counter demonstration[5].

In April 1983 the NF claimed in the press to be growing, with new branches, and the ability to engage in “overt” street activity.[6] According to Loughlin “an intensified recruitment drive in Northern Ireland took off in 1983 with [organiser] Jim Morrison claiming the formation of six new units in north and east Belfast, Ballymena, Ballymoney, Enniskillen and Larne.[7]

Loughlin continued “The new National Front leadership hoped that the removal of Martin Webster at the party’s AGM of 1983 would allow the organization to make greater progress in the region in the furtherance of which accusations of National Front sympathy for Nazism were rejected, with reference to the National Front’s own ex- servicemen’s Association. At the same time, criticism of the conditions loyalist prisoners in Northern Ireland jails had to endure was emphasised, together with attacks on the supergrass system”.[8]

They held a public meeting in Coleraine Town Hall on July 9th, 1983, Coleraine becoming the first council in England, Scotland, Wales, or Northern Ireland, to allow a NF meeting in council-owned property[9]. By 1984 the Front claimed to have 100 members in Belfast and dozens more in the working class and industrial town of Coleraine, on the border of County Derry and County Antrim[10].

A Lethal Threat

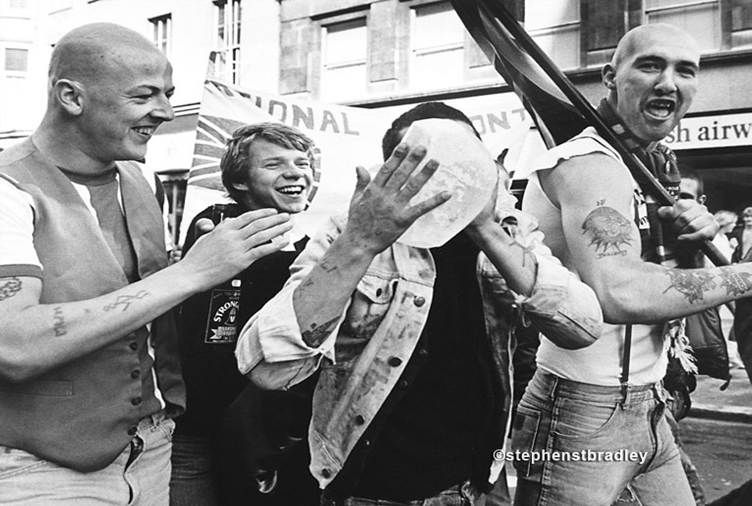

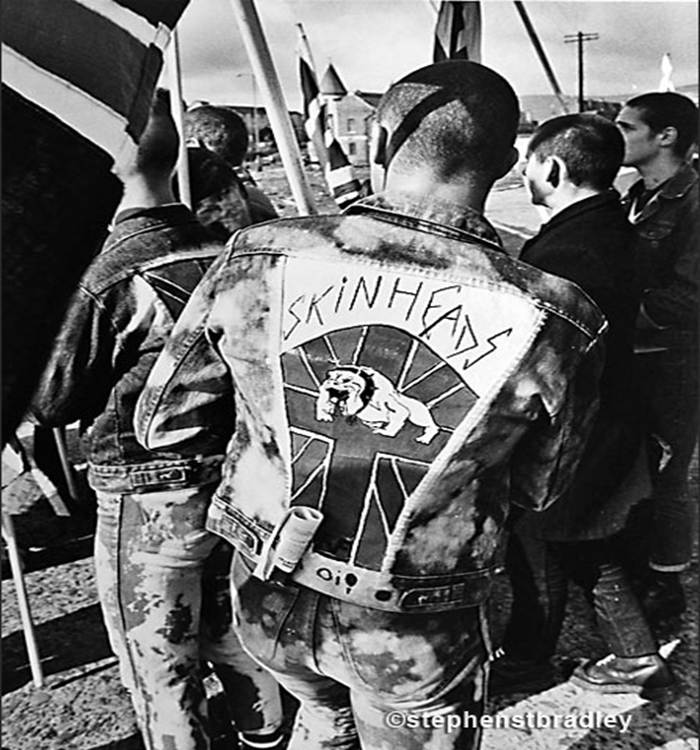

The NF were particularly concerned to recruit youth: “skinhead activity was cultivated by Joe Pearce, young National Front chairman”……. who was….. “concerned to make a mark in Northern Ireland, and building on his expertise as a street agitator, fertile ground seemed evident in the growth of a skinhead section, especially in Belfast”.[11]

The “skinheads” associated with the NF routinely engaged in violence, for example attacking those attending a gig in the Ulster Hall, Belfast of The Specials and The Beat in 1981.[12] Adair and his associates formed a fascist “oi” band which played in local clubs. In April 1983 three of the young members of the National Front killed a homeless Catholic man with alcohol problems, Patrick Barkley, by battering him with a concrete block, in the Lower Shankill area of Belfast).[13] Joe Pearce denied that he had advocated killing anyone, though the pages of The Ulster Front Page, produced for the Northern Ireland Young National Front, glorified attacks against Catholics and members of ethnic minorities..[14],[15] The three were convicted of manslaughter and imprisoned on one of the paramilitary wings at the Maze Prison. By May 1984 “NF Skinz” was reported to have 200 members.[16]

The National Front gave a platform to George Seawright, an extreme sectarian member of Belfast City Council and the Assembly at Stormont, in an article entitled “An Ulster Loyalist Speaks Out”. [17] Seawright openly endorsed the racist policies of the NF and in 1984 reportedly stated that Belfast City Council should buy an incinerator “to burn Roman Catholics and their priests“. After his death was revealed to be a member of the paramilitary Ulster Volunteer Force.[18]

Sometime in 1984 Johnny Adair and his cohorts joined the ranks of the Ulster Defence Association/Ulster Freedom Fighters. When we met the NF on the streets in June 1984 we do not know if Adair and the others were present, but we do know that members of NF SKINZ were.

Building the Labour Movement Campaign Against Fascism

Coleraine was an industrial working-class town, and also home to a new university which was established there in 1968 just before the Troubles erupted. Militant first put down roots in Ireland in the northwest of the country. Our first comrade was Paul Jones, from a Protestant background in Derry. He was won to Militant in England and returned to Derry just in time for the events of the civil rights movement in 1968 and 1969. In those first few years, our early members were grouped in Derry, Belfast and in Coleraine. The organisation developed in the south of Ireland slightly later, when John Throne returned from England in 1970.[19] ,[20] The Coleraine branch of Militant grew out from the New University of Ulster and included Bridget O’Toole,[21] who died in 2011, and Alex Wood and Roger Shrives who returned to England in the mid-1970s. By the 1980s we had a branch in Coleraine town itself, which included both Catholic and Protestant members.

We understood the threat represented by the National Front. It was a fascist party, and it needed not just to be countered, but checked robustly from its infancy. If it were allowed to grow it would become a real threat to working class organisations and people of colour and other minorities in Northern Ireland. The association between fascist groups and the loyalist paramilitary armed groups always added an extra dimension of threat and lethality.

When we became aware of the organising activity of the National Front in Coleraine and their intent to organise a march in the town, we began to consider how we would counter this as the National Front went through the formal process of asking the local Council for the use of the town hall for a public meeting.

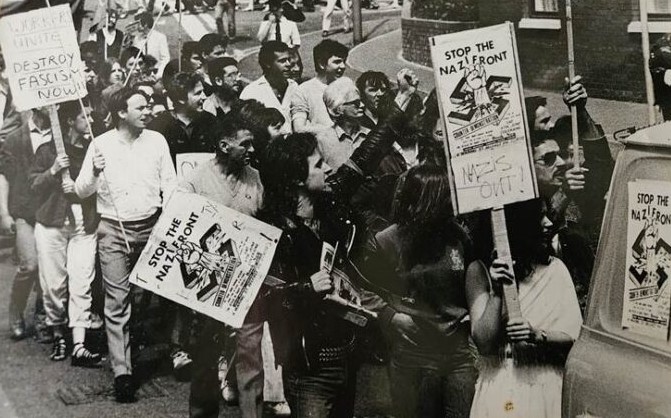

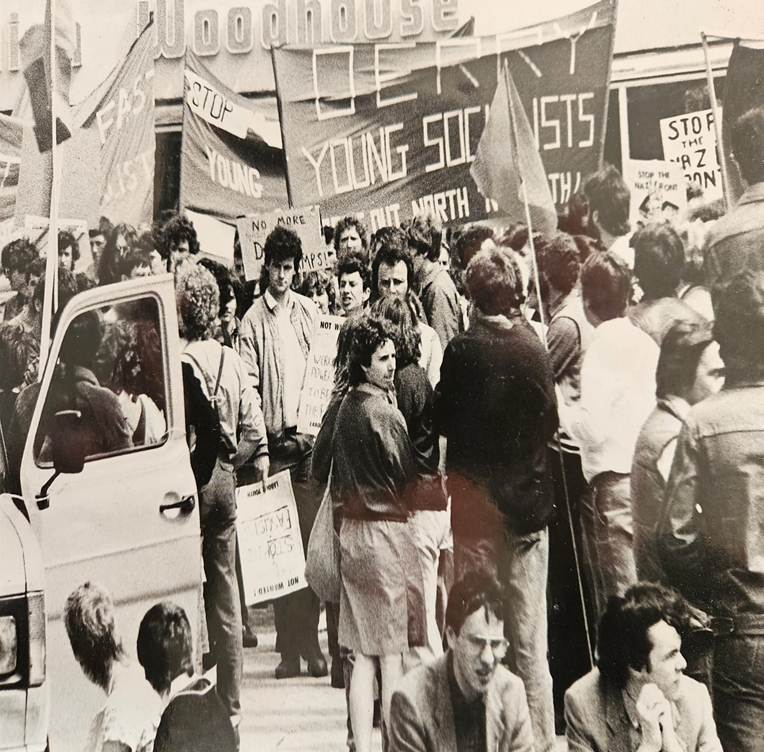

As with all our serious campaigning work we approached our tasks on several fronts. We ensured that political education of the comrades was central; we orientated to the organised working class in the unions; and we consciously sought to build our ranks through our campaign. At the time, our focus was always and resolutely on the working class, and we always worked through class-based organisations. For this reason, we established the “Labour Movement Campaign Against Fascism” to counter the NF, in the spring of 1984, and sought to gain support from trade union branches, trade unions and trades councils. Our efforts to achieve this support were sometimes opposed by the right-wing union bureaucracy and by Communist Party influenced officials and activists but were met with considerable success, nevertheless.

We achieved support from the Civil and Public Service Association (CPSA), the Amalgamated Transport and General Workers Union (ATGWU), the Amalgamated Union of Engineering Workers (AUEW), the National Union of Seamen (NUS), the National Union of Public Employees (NUPE) and the Irish Transport and General Workers Union (ITGWU). The ATGWU, particularly because of the outstanding role of the Irish Regional Secretary Matt Merrigan, was to the fore in assisting the campaign. Support also came from Fermanagh, Coleraine, Belfast and Ballymena Trades Councils.[22]

Despite this groundswell of support the officials of the Northern Ireland Committee of the Irish Congress of Trade Unions (NIC-ICTU) were largely unhelpful and even hostile to the attempt to organise a counter demonstration. The response to the call for a protest showed that the activists in the labour movement understood that it was not enough simply to condemn the National Front verbally, but that workers had to show their strength on the streets. The Northern Ireland Officer of the NIC-ICTU, Terry Carlin, attempted to frustrate the organising of a successful counter demonstration at several junctures in the campaign. He distorted the initial position of Coleraine Trades Council by saying they were opposed to a counter demonstration when the reality was that they were unsure whether enough people could be mobilised on the day to keep the marchers day from attack and were understandably cautious for this reason. When it was clear that the counter demonstration was going ahead, the Trades Council held a second meeting and passed a motion calling for a mass presence of workers and others at the march. Even then Carlin continued to create confusion by stating publicly that the Trades Council had serious misgivings about the counter demonstration.[23]

Party Education and Local Campaigning Work

Within the party, we sought to educate our members and asked everyone to read the pamphlet “Menace of Fascism What it is and How to Fight it” by Ted Grant.[24] We discussed the pamphlet and our specific approach to the National Front in Coleraine through all our branches.

We began to do work everywhere where we were active, leafletting and setting up stalls, aiming to draw in new layers, especially of young people, to assist in the campaign (utilising thousands of the Labour Movement Campaign Against Fascism poster at top of article-one of many striking posters designed by comrade Benny Adams).[25]

We organised a public meeting in Belfast on March 3rd and saw off a group of fascists who tried to enter the hall to attack those inside.[26] In Coleraine we worked on the ground, mindful of the security of the comrades. We knew some of the National Front members in the town: they were young and not seasoned fascists, and we sought to win them away from the path they were on and towards the ideas of socialism. In one case, we were successful in doing so, and a young person was recruited to the Young Socialists.

We campaigned in the town-with stalls and leafletting-for access to good leisure facilities for young people. This was, and is, exactly the type of class-based issue which can mobilise young people and attract them to socialist ideas. If such issues are not taken up by socialists, the field is left open to fascists to exploit-tactics that are employed today by the far right.[27] Campaign statements were covered in the local press where we warned that fascism would destroy all democratic rights if it were ever successful. [28],[29]

Organisationally, we began to make our plans for the counter demonstration. We knew that it was vitally important that we outnumber the fascists and that we had to be prepared for physical confrontation if necessary. We learned from the experience of the comrades in Britain in our work, especially the Battle of Lewisham in 1977 where Militant supporters, working through the Labour Party Young Socialists provided a solid phalanx of anti-fascist demonstrators.[30] At this time Militant supporters were well organised with three branches in East Belfast (Cregagh, Sydenham and Castlereagh), two in South Belfast (Lisburn Road and Ormeau Road), two in West Belfast (Upper and Lower Falls) and one in North Belfast, and two branches in Derry (Cityside and Waterside) and branches in Ballymena, Enniskillen and of course Coleraine. We also had a presence in Ballymoney, Larne, Omagh and Downpatrick. An experienced cadre, with comrade Peter Hadden[31] to the fore, provided considered, sober and serious leadership.

The NF were attempting to stoke the fires of sectarianism. We reported that “in the fortnight before their demonstration, the National Front, who had been shocked to discover that a campaign had been mounted against them, attempted, in desperation, to stir up sectarianism in Coleraine, and they put up National Front posters with a “Hang IRA” slogan, and attempted to spread malicious lies about links between the YS and Republican groups”. [32]

We countered all their attempts to create division, campaigning outside local workplaces and on the streets and “time and time again, we were approached by local people as we put up posters or handed out leaflets at the factories and thanked us for the work we were doing. Several workers took handfuls of leaflets to distribute to their friends”. [33]

Two weeks before the demonstration, we organised a day of action in Coleraine, and again, on that day, we ensured that we had adequate numbers in the town and the comrades were never left isolated or vulnerable.

Calls to Ban March

On the day before the march, the Belfast Telegraph reported that Secretary of State, Jim Prior did not intend to ban the “controversial National Front parade”. He stated that he, “had full confidence in the RUC’s [Royal Ulster Constabulary-the armed and militarised police force] capability to handle the march”. He went on “I don’t wish to ban it. The police think they can deal with it. I don’t wish to elevate it to something which is likely to give them extra publicity. The RUC said they will keep an equally tight control of planned counter demonstration”).[34]

A RUC spokesman added, “police activities will be geared to prevent any public disorder arising, and the parades will be policed”. It was reported that two Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP-the main nationalist party then, supported by many Catholics) councillors, John Dallat and Gerry O’Kane, urged the other political parties on Coleraine Council to reconsider their decision to allow the National Front to use the town hall.

Local DUP Assemblyman and former Mayor Jim McClure rejected their call arguing that whilst “all councillors condemn the National Front…….the decision to allow them inside the Town Hall was taken because to deny that to the organization would result in harm, in them holding an open-air rally that could lead to violence”.

McClure opposed the counter demonstration: “the National Front should never have raised its ugly head Coleraine, but he felt that a counter demonstration could do as much harm itself. He argued that last year, a small National Front rally had passed off without incident because few people had known it was taking place”.

He placed bureaucratic obstacles in the way of reversing the decision: “The decision to grant use of the Town Hall was taken at a private session of the Council, and Mr. McClure said it was now too late to convene a special meeting to withdraw the permission”.[35]

June 9th Arrives

The front page of the Belfast Telegraph on the 9th anticipated the day in a short article stating, “the police……on alert as rival rallies take place in Coleraine”.[36] We organised three buses from Belfast, one bus from Derry and cars from other areas. One of the buses was stoned on its way to the counter protest, near Ballymena, and in the confusion the group of comrades waiting to be picked up in Ballymena were left behind.

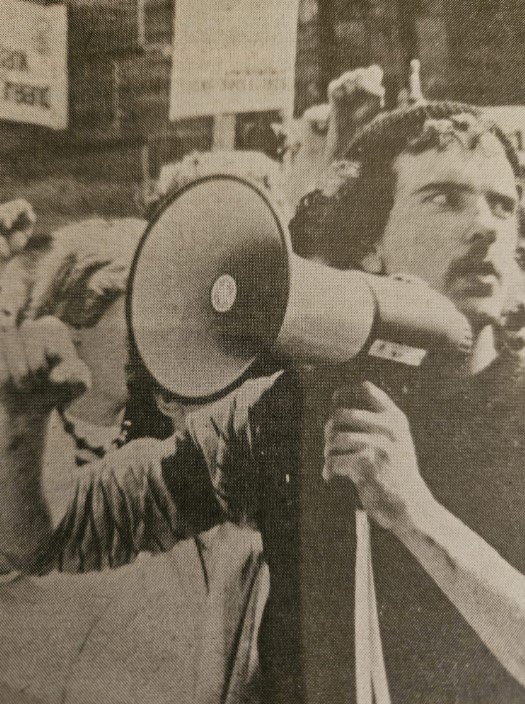

The marchers proceeded from the railway station to the town hall, winding our way through the streets of Coleraine, carrying placards with heavy sticks, which have an obvious dual use. The Telegraph reported that “the Young Socialists outnumbered the National Front by four to one, and their support grew as they marched through the town to the town hall”. [38] It was reported that two SDLP councillors who had opposed the NF use of the town hall, John Dallat and Gerard O’Kane, had taken part in “the demonstration of the Young Socialists”.[39]

The Dublin based music and current affairs magazine Hot Press reported more cynically that the counter demonstration was not met with approval: “the people of Coleraine stood on the side of the street. “They’re against the National Front, are they against the Provos [a nickname for the IRA], but?” a man asked. The people on the side of the street were hostile to the march against the National Front which consisted of a number of left-wing groups. They marched to the left of the town hall and were cordoned off by the RUC”.[40]

On arrival at the town hall, the anti-fascists were corralled on one side of the square by the Royal Ulster Constabulary. The Telegraph reported on the short rally: “the Young Socialists from Londonderry, Belfast and Coleraine carried placards and banners protesting against the decision to allow the National Front rally to take place. Former Derry Trades Council leader Mr. Bill Webster told the crowd of about 500 that the decision was “sick, particularly as the march was taking place in the week when the widows of France wept as they remembered those lost on D Day””. [41] [42]

When the fascist march arrived, there was a cacophony of noise from both sides. According to the Telegraph “the police kept the two groups apart and formed human barricades to separate the groups who chanted and jeered at each other outside the town hall”. [43]

The Hot Press report captured the tense atmosphere, with violence just beneath the surface. It explained that as the NF march approached “the shouting could be heard first….. then you saw them coming. Skinheads, young lads waving a huge number of flags and banners. Maybe 150 of them all roaring and waving. Staring you straight in the eye….They took a circuitous route through Coleraine and then marched straight up to the town hall. There was applause from a section of the people on the street…..

“The two marches began to roar at each other; the National Front people noticed that there were several blacks among the opposition. They singled them out for abuse. The RUC had to hold them back. They were pushed into the hall and the doors were closed”[44]

The fascists marched quickly and straight into the town hall. According to Loughlin the significance of the event to the National Front “was reflected in the roster of speakers, which, apart from the chairman, Jim Morrison, the Belfast National Front organiser, included Phil Andrews, National Front Directorate member, Joe Pearce, chairman of the young National Front and Ian Anderson, National Front Deputy Chairman”. [45]

As reported by Hot Press: “At first the press was excluded. We stood outside and waited to be let in. It took ten minutes or so before we were allowed up the stairs”. [46]

When they were admitted the Telegraph reported “the 150 National Front demonstrators, mainly skinheads, heard a speech by the Young National Front organizer Mr. Bill Anderson, calling the counter demonstrators scum”. [47]

Hot Press gave a more detailed account of the platform speeches-the NF were clearly attempting to capitalise on anti-IRA sentiment: “The speeches….congratulated the National Front for stopping the Provos marching in Britain to commemorate Bloody Sunday when the Paras “rightly” shot people in Derry”. [48]

The reporters remained in danger: “the third speaker attacked the press and pointed to us all sitting at the back. All the time they spoke skinheads waved flags from the stage. A few blokes began to point at us and ogle us. Soon, these blokes approached us and told us to get out. A few more stood around. Get out. You can take notes in the Free State. They wanted our notebooks; they tried to take them. As we went down the stairs a number of National Front members approached us from the hall downstairs. Behind us, other members, our assailants, watched us carefully. We made our way out as best we could”.[49]

The anti-fascists returned home in good order, still mindful of the risk of attack. On our return journey, one bus stopped on its way back to Belfast at a small petrol station. As 50 anti-fascists spilled out of the bus, we realised that a carload of fascists was trapped on the forecourt where their car had broken down. The look on their faces clearly indicated that they expected physical violence, but instead, we simply surrounded the car for a period, noted its details and photographed the occupants. We then resumed our return journey.

A Resounding Defeat for the Fascists

On the Monday after the NF march and counter demonstration the Belfast Telegraph was focused on a statement from “Coleraine traders” who were reportedly “angry at the damage caused by the National Front”. The Telegraph stated, “shopkeepers in Coleraine are angry at the National Front March and rally in the town at the weekend which may have done irreversible damage to the town’s image”. Steven Smith of the Chamber of Commerce was quoted stating that shop owners were “very, very angry and have little confidence in a council which can make a decision like this”. [50]

We knew the day was more significant than disrupted shopping. In the July/August 1984 edition of Militant Irish Monthly, our headline read “Huge Turnout Against National Front”. We reported: “the mood amongst the Young Socialists and trade unionists on the anti-fascist march was electric. Everyone, from 13-year-old school children to old age pensioners, was determined to let the National Front, know that the working class would not tolerate their presence. Hundreds of local people stood outside their doors, watching the march and applauding the YS banners and placards”. [51]

We estimated that 700-800 attended the march, and 350 of these were from Coleraine. The National Front only mobilized 120 for their demonstration. Loughlin quotes similar numbers from a New Statesman article which concluded: “it was reflective of their popular appeal that attendance to the 1984 Coleraine event was estimated at around 150 National Front members and supporters, many from England, while around 600 anti-National Front demonstrators gathered outside, numbers undoubtedly more realistic than the National Front’s own estimate of 300 with only 30 from England”. [52]

In our account, we explained how “their credibility as representatives of the master race was undermined when an angry woman ran out of the crowd, boxed her 14-year-old son around the ears and dragged him out of the National Front March and home for a good telling off”. We estimated that no more than 20 local people took part in the NF march. [53]

We argued that “the demonstration was so successful that the National Front will have to reconsider holding any more marches or meetings in Northern Ireland. They have suffered a huge setback due to the counter demonstration. In particular, the response of the trade unions was very significant. Workers’ organisations can organise successfully to smash fascist organisations, as they did in Britain in the 1970s and the full power the working class must be used to smash the National Front, wherever it raises its ugly head”.[54]

The Aftermath

Over the following two years the National Front split into two factions, the “Flag Group” and the “political soldiers”. The harder line and more violent of the factions, the “political soldiers”, were dominant in the North. They intervened into the unionist and loyalist protests against the Anglo-Irish Agreement in 1985-1986 to gain support, and by the autumn of 1986 were claiming 500 members.

Their Northern Ireland leader was interviewed for a BBC television expose of NF infiltration of unionism and proudly associated his group with a riot and gun attacks on police in the Rathcoole estate in Newtownabbey (a National Front member had spoken from the platform at an anti-Agreement rally, and afterwards, rioting broke out and the police were fired upon by gunmen). The same Front speaker marched alongside Democratic Unionist Party leader and future First Minister of Northern Ireland Ian Paisley at a Hillsborough protest in the same period. These attempts at re-building the Front ultimately proved futile however and it had all but disappeared within a few years.

We could not take unnecessary risks, but we did take a calculated risk, and the risk paid off. The strength of the Labour Movement Campaign Against Fascism was its orientation to the organised working class. The National Front understood very well that they could not take on the organised might of the workers movement. Despite their influence with some paramilitary figures and probable access to weaponry they did not attack anyone associated with the Labour Movement Campaign.

Despite their efforts the fascists were rejected by the working-class people of Coleraine. The National Front never again attempted to march or meet openly anywhere in Northern Ireland. It never became the respectable force they sought to be and after June 1984 it was no longer able to demonstrate on the streets in daylight. Nor could it claim to represent working class people. It could only operate in the shadows and on the fringes of the paramilitary groupings. Militant, the Young Socialists, and the Labour Movement Campaign Against Fascism can take credit for this victory.

[1] Loughlin, James. Fascism and Constitutional Conflict. The British Extreme-Right and Ulster in the Twentieth Century. Liverpool University Press, 2019.

[2] David Lister and Hugh Jordan. Mad Dog: The rise and fall of Johnny Adair and C Company. Mainstream Publishing, 2004.

[3] Loughlin, p 251

[4] Loughlin, p 251

[5] Militant Irish Monthly, No 123, June 1984

[6] “Six new units set up: NF” Belfast Telegraph, 13th April 1983.

[7] Loughlin, pp 244

[8] Loughlin, pp 244-245; Supergrasses were informers who gave information to the state on multiple individuals-up to 50 or 60- in return for a reduced sentence.

[9] Loughlin, p 245

[10] Loughlin, p 245

[11] Loughlin, pages 250-251

[12] McDonald, Henry & Cusack Jim, (2004) UDA-Inside the Heart of Loyalist Terror. Dublin: Penguin Ireland, pp167-168.

[13] Belfast killers had links with the National Front, Irish Times 30th April 1984.

[14] Loughlin, p251; The Ulster Front Page engaged in vicious verbal attacks against both people of colour and Catholics, using highly offensive and unrepeatable language against the former and describing the latter as “human vermin” and “pigs”. It encouraged physical attacks on both.

[15] Pearce has now disowned his past, has adopted an ultra-conservative Catholic position, and is a prolific publisher of Catholic commentary, biographies and reviews.

[16] Loughlin, p 251

[17] Nationalism Today, Number 18-19, 1983 (quoted in Loughlin).

[18] Seawright was assassinated by the Irish Peoples Liberation Organisation (a splinter from the Irish National Liberation Army) in 1987. UVF affiliation was claimed in 2006: BBC News website, 23rd August 2006, “Burn Catholics’ man was in UVF”.

[19] See The Rise of Militant, Peter Taaffe, Chapter 4: Northern Ireland: The Troubles. “Up to the late 1960s Militant had no support outside of Britain. Fortunately, Paul Jones from Derry was won to Militant’s ideas while he was studying in London just before the outbreak of the “Troubles”. . https://www.socialistparty.org.uk/articles/97752/23-06-1995/northern-ireland-the-troubles/

[20] See obituary John Throne: https://www.irishtimes.com/life-and-style/people/john-throne-obituary-leading-irish-marxist-from-rural-protestant-background-1.4032416

[21] Bridget was originally from Cornwall in England. She moved to Coleraine, in Northern Ireland in the late 1960’s. where she taught creative writing in the New University. She was a founding member of the Militant in Ireland but was no longer active in revolutionary politics by the 1980s.

[22] Militant Irish Monthly, No 123, June 1984.

[23] Militant Irish Monthly, No 123, June 1984.

[24] Menace of Fascism What it is and How to Fight it by Ted Grant. Militant Publications, London, 1978.

[25] See Obituary Ciaran Mulholland: Benny Adams, A fighter for socialism. Against the Stream website. https://againstthestream.blog/obituary-benny-adams-1949-2014/

[26] Comrade Jason Weir, who died in 2023, led the physical defence of a Militant public meeting in Belfast against fascists who tried to enter the hall to attack it. From a Protestant background he was a member of the vibrant Ballymena branch of Militant in the 1980s and 1990s. He was fiercely anti-racist, anti-homophobia, and anti-misogyny, and was known to call others out when they expressed any trace of such ideas. See Obituary Niall Mulholland: Jason Weir. Militant Left, February 23, 2023.

[27] Coleraine Young Socialists in Action, Militant Irish Monthly, No 122, May 1984, Alison Grundle.

[28] Labour challenge to march by NF. Newsletter May 23rd, 1984.

[29] Irish News May 23rd, 1984.

[30] Roger Shrives, Lewisham 1977: When socialists and workers defeated the far-right National Front, The Socialist, August 23rd 2017. https://www.socialistparty.org.uk/articles/26021/23-08-2017/lewisham-1977-when-socialists-and-workers-defeated-the-far-right-national-front/

[31] See obituary Peter Hadden, The Socialist. https://www.socialistparty.org.uk/articles/9545/19-05-2010/peter-hadden-an-inspiring-life-for-socialism/

[32] Militant Irish Monthly, No 122, May 1984.

[33] Militant Irish Monthly, No 122, May 1984.

[34] Belfast Telegraph, June 8th, 1984; the Secretary of State was the British government minister who effectively administered Northern Ireland after the local devolved government was suspended amidst escalating violence in 1972.

[35] Belfast Telegraph, June 8th, 1984

[36] Belfast Telegraph, June 9th, 1984.

[37] Obituary. Frank McCallan, Irish Times, Sept 9th, 1996, https://www.irishtimes.com/opinion/frank-mccallan-1.84376

[38] Belfast Telegraph, June 11th, 1984

[39] Belfast Telegraph, June 11th, 1984

[40] https://magill.ie/archive/diary-july-1984-map-reading-much-and-national-front

[41] Belfast Telegraph June 11th, 1984.

[42] See Obituary Bill Webster Irish Times August 23rd, 2014, and Ciaran Mulholland: Bill Webster-Unbending fighter for his class, 2014. https://againstthestream.blog/obituary-bill-webster-unbending-fighter-for-his-class-1941-2014/

[43] Belfast Telegraph June 11th, 1984.

[44] https://magill.ie/archive/diary-july-1984-map-reading-much-and-national-front

[45] Loughlin, p245.

[46] https://magill.ie/archive/diary-july-1984-map-reading-much-and-national-front

[47] Belfast Telegraph June 11th, 1984.

[48] https://magill.ie/archive/diary-july-1984-map-reading-much-and-national-front

[49] https://magill.ie/archive/diary-july-1984-map-reading-much-and-national-front

[50] Belfast Telegraph June 11th, 1984.

[51] Militant Irish Monthly, No 124, July/August 1984.

[52] Loughlin quoting Kevin Toolis, Opening a New Irish Front, New Statesman, 15th June 1984, p 249.

[53] Militant Irish Monthly, No 124, July/August 1984.

[54] Militant Irish Monthly, No 124, July/August 1984.

[55] See Belfast Telegraph, January 27th, 2009: “Colm McCallan, a Belfast Catholic, was aged 25 when he died; but he was still a student, though married with a child. He was studying hard for exams and he left his Ligoniel home in the early hours of July 14, 1986, telling his wife he wanted a breath of air. But he was chased into a laneway by three gunmen of the UVF who shot him three times in the head. A doctor found him, still conscious, where he had crawled 40 yards into an adjacent avenue at 2.30am. He died in hospital”.

[56] Militant July 18th, 1986: “an ex-production worker at Michelin [tyre factory] and a member of the Amalgamated Transport and General Workers Union. He became a Militant supporter in 1981. Extremely proud of his socialist ideas, he once remarked that his decision to join with Militant was the most important he had ever made….now he has fallen victim to the very sectarianism against which he fought”. https://www.marxists.org/history//etol/newspape/militant/1986/807-18-07-1986.pdf

[57] Lost Lives: The stories of the men women and children who died as a result of the Northern Ireland troubles. David McKittrick, Seamus Kelters, Brain Feeney, Chis Thornton and David McVea. Mainstream Publishing, Edinburgh and London, 2012. p 1042-1045: “…Colm McCallan was a supporter of the left-wing socialist paper Militant. A trade union colleague told the Irish News….”He was a very sound fellow who hadn’t an ounce of sectarianism in him””.