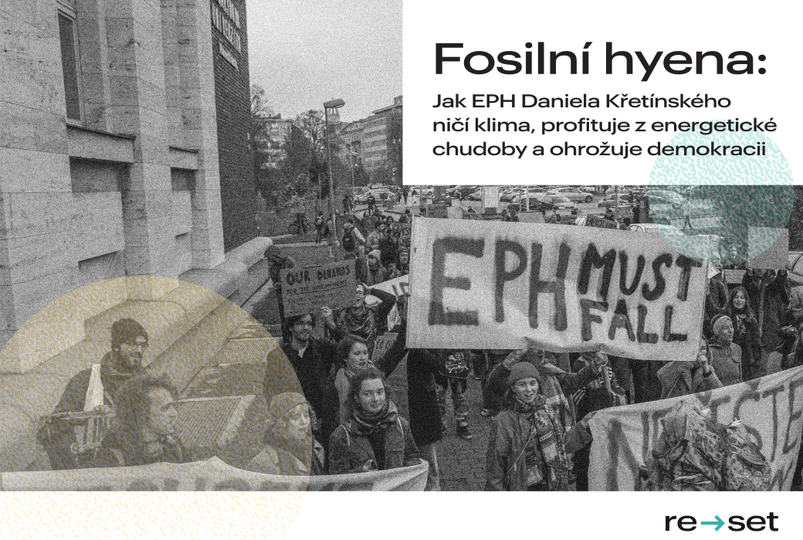

On September 8-10, an international conference was held in Čáslav, Czech Republic with the objective of mobilizing the environmental movement all across Europe towards a campaign targeting the EPH corporation (Energetický a Průmyslový Holding) and its owner, the Czech oligarch Daniel Křetínský, who is operating a dirty business of capturing coal plants to obtain government money for new gas infrastructure projects. Climate activists from multiple countries reunited with the locals struggling against the expansion of a hazardous landfill, shared knowledge and experience and made plans for transnational action against EPH and its funders.

We had the opportunity to discuss with Radek Kubala, member of the Czech social and ecological platform Re-set, who initiated the conference, and we found out more about Křetínský’s fossil fuel, media and football club empire, his tight grip on the Law Faculty in Brno, and the necessary actions in order to counteract his power and harmful practices.

Q: You have been researching Křetínský and you initiated this conference. How did you begin this initiative against Křetínský and his business?

RK: My colleagues and I, who are part of Re-set, have been involved in the climate movement for quite some time. We started noticing the steady rise of the EPH company, owned by Daniel Křetínský, and its increasing influence in the energy sector across Europe. Some of us had participated in the Ende Gelände action in Lausitz in 2016. The EPH acquired coal mines and power plants in Germany’s Lausitz region, effectively becoming one of the largest coal companies in Europe. It became evident to us that EPH was rapidly expanding and becoming one of the leading climate adversaries in Europe.

During the discussions with fellow climate activists from around Europe, we realized that there wasn’t a coordinated campaign against EPH. While there were separate struggles in places like Lausitz, Italy, and now Great Britain, there was no overarching campaign targeting EPH. We felt that this was a crucial gap that needed to be addressed. We saw EPH as a significant player that was hindering climate action, delaying coal phase-outs in various countries, and promoting the construction of new gas infrastructure throughout Europe.

Given our understanding of Daniel Křetínský’s background and how he had amassed such power, we believed that focusing on this issue was essential. We considered it our responsibility to take action. Therefore, we chose EPH as our central campaign topic.

Q: During the conference, you mentioned how Křetínský is exploiting the green transition for his own profit. Could you briefly describe his business model, particularly how he benefits from compensation? Why do you think it’s crucial for climate activists to understand and combat this business model?

RK: Certainly. EPH’s rise to power is largely rooted in a shady deal with the Slovakian government, where they gained control of the pipelines transporting gas from Russia to Europe. This provided them with a stable income, which they used to fuel their expansion in the European energy sector. They invested this money in acquiring coal power plants and mines in Germany and other regions. Interestingly, they targeted assets that companies like Vattenfall or Uniper were eager to divest due to the negative reputation of coal.

However, Křetínský’s strategy wasn’t driven by a love for coal; it was purely profit-oriented. He saw an opportunity in profiting from the coal phase-out. He applied pressure on governments, successfully securing substantial compensations, such as the nearly 2 billion euros compensation from Germany. Furthermore, in various countries, he sought public funds and used them to develop new projects, primarily focused on expanding gas infrastructure. EPH holds the most extensive plans for gas expansion among all European energy companies.

Their business approach involves taking public money allocated for coal phase-outs and redirecting it toward building new gas infrastructure. Their success can be attributed to their indifference to coal’s reputation, as well as their relentless pursuit of profit. We refer to this strategy as a “vulture-like strategy” because it’s driven solely by financial gain, without regard for environmental concerns. Understanding the financial mechanisms, including the role of credit in Křetínský’s business, is crucial for climate activists in countering this harmful model.

Q: Regarding the connections between EPH and banks, what conclusions have you drawn about the ties between the banking system and Křetínský, as well as other coal and fossil fuel magnates?

RK: It’s rather intriguing because Křetínský seems to be constructing a particular image of himself as an oligarch and wealthy individual who portrays himself as liberal and benevolent, especially in Western countries. He invests in reputation-building efforts, such as buying football clubs like West Ham, to cultivate a positive public image. This positive image assists him in accessing markets in countries like France and the UK. It also helps him maintain favorable relationships with banks.

Surprisingly, he collaborates with major Western banks like Unicredit Bank, Societe Generale and ING, among others. Additionally, since 2021, he has been receiving funding from the Bank of China, illustrating his ability to navigate both Western and Eastern financial worlds. It’s as if he wears two faces, one that appears friendly to the West while also seeking capital from the East. He effectively acts as a bridge between Western and Chinese or Russian capital to expand his empire.

We are currently in contact with Societe Generale, urging them to cease their collaboration with EPH. Although they express curiosity about Křetínský, they don’t perceive him as a problematic figure, which strikes us as somewhat perplexing.

Q: You mentioned Křetínský’s involvement with football clubs, particularly Sparta. What is the general sentiment among the supporters and fans of the Sparta club regarding Křetínský? Are they aware of his ownership, and do they generally support him, or is he rather viewed as part of the establishment in football?

RK: The fans of Sparta are generally not perceiving Křetínský as a political figure or someone with a specific political agenda. Their awareness of him is quite high, primarily because he uses his ownership of football clubs as a means to enhance his public image. Unlike EPH, which maintains a low profile, Křetínský leverages football clubs to establish his presence in the public eye. Many people recognize him as the owner of Sparta and, more recently, as the owner of West Ham.

Fans tend to be influenced by the performance of the club. If the team faces issues or experiences a period of poor performance, fans may express dissatisfaction with Křetínský. There have been some protests by fans in the past, but these were typically related to club-specific problems, such as perceived insufficient financial support for the team. Overall, Křetínský’s ownership of the clubs does not generate significant political controversy among the fans.

Q: It seems that Křetínský is actively involved with the law faculty at the Masaryk University in Brno, his alma mater. Could you elaborate on the procedure you mentioned, where law students are essentially groomed to work for Křetínský? Additionally, has there been any resistance or pushback from students against Křetínský’s involvement in the university?

RK: Křetínský has established a notable presence at his alma mater, the Masaryk University Law Faculty in Brno, which is the second-largest city in the Czech Republic. Here, he has forged a beneficial partnership for himself. EPH sponsors the law department within the faculty, and individuals from EPH are even involved in teaching courses at the university. Moreover, students often pursue internships with EPH. In essence, it appears that Křetínský is scouting for emerging law experts and talents, financing their education, and eventually enlisting them for his own business endeavors.

When this arrangement first began, there were protests from students, both prior to and after their involvement with EPH. The Universities for Climate, a movement in the Czech Republic, initiated a campaign against this partnership, seeking to politicize the issue. Some faculty members also expressed concerns and wished to take action, especially considering the extension of the agreement.

However, while there are students who have voiced their opposition, they have not yet achieved significant influence or power in the matter. Nevertheless, the situation is being actively discussed within the faculty, and some individuals are attempting to raise awareness and gather support to end this cooperation, as they view it as problematic. This remains a noteworthy issue within the law faculty, and efforts to persuade the faculty to discontinue this collaboration continue.

Q: What measures can be taken against Křetínský, and how can the climate movement in the Czech Republic, Europe, and even from outside Europe, combat his influence and business model? What strategies can be employed to challenge him effectively?

RK: There are several avenues through which the climate movement can take action against Křetínský and his business model.

First, there’s the financial angle, which involves targeting the banks and insurers that support Křetínský’s businesses, including EPH. This strategy is already being pursued.

Second, there’s the front line of resistance, which involves supporting and collaborating with local communities fighting against specific projects connected to EPH. For instance, there are local resistance movements in places like Mantova, Italy, that oppose EPH initiatives.

Third, there’s the regulatory and legislative angle, which entails advocating for European regulations that hold large corporations like EPH accountable. This may involve pressuring politicians and the European Union to adopt measures that address corporate power and influence.

Additionally, long-term strategies include building connections with unions within the company and in other countries. Supporting a socio-eco-just transition is vital, as EPH’s business model is often incompatible with such transitions.

It’s crucial to recognize that EPH serves as an illustrative example of how the system functions, revealing how money and powerful oligarchs like Daniel Křetínský can corrupt politicians and manipulate rules to serve their interests. Thus, the campaign against EPH also serves as a means to highlight systemic flaws and raise awareness about the need for systemic change.

In summary, there are various strategies available to the climate movement to combat Křetínský’s influence and business model, ranging from financial pressure to grassroots resistance and long-term advocacy for regulatory change.

Q: Why did you choose Čáslav, the city known for its struggle with the hazardous waste dump, as the location for this conference and initiative?

RK: The selection of Čáslav as the conference location was driven by our desire to highlight the importance of frontline communities in the fight against corporate power. While EPH may not be as dominant in the energy sector in the Czech Republic, we were working on identifying areas where Daniel Křetínský’s business model faced opposition and was part of ongoing struggles. Čáslav emerged as such a location, where there was a powerful opposition movement against the waste dump.

As we delved deeper into the situation in Čáslav and engaged with the local community, we realized that it was a fitting place to host the conference. The people we met here were truly inspiring in their dedication to their cause. It felt like a natural choice to bring our initiative to Čáslav and collaborate with the local community. In the long term, it makes sense to tell the story of Křetínský’s business practices through the real experiences of communities affected by them.

Q: You mentioned your efforts in connecting with unions, and it seems like there has been some progress despite initial opposition. Can you share more about the current state of your engagement with unions in the Czech Republic? Have there been successful collaborations or ongoing discussions, and how do unions perceive the need for a just and social ecological transformation?

RK: Our journey in engaging with unions in the Czech Republic has been quite interesting. Initially, when we started as anti-coal campaigners, especially in the northern Bohemia region, we encountered opposition from unions, particularly what we refer to as “yellow unions.” These unions were closely aligned with the coal industry, and their leadership included individuals who were on the boards of coal companies. They actively worked against our efforts.

However, over the years, we have slowly initiated conversations with different union representatives. There have been notable changes in the structure and attitudes of Czech unions. They have become more open to discussions with us, which is a positive development. Recently, there was even a union protest where they allowed members of the Czech climate movement to deliver a speech. This marked a significant step forward after years of negotiations.

Nevertheless, building a robust and productive relationship with unions remains a long-term endeavor. We are continuously working on establishing connections, engaging in discussions, and advocating for the ecological transformation to be both social and just. Many people within Czech unions are recognizing the inevitability of this transformation. However, there is still apprehension about the potential impact on jobs, and some may wish to slow down the process. It’s a complex issue that requires ongoing dialogue and cooperation.

When union members see business figures like Křetínský profiting from the transition while they might be at risk of losing their jobs, it sends a powerful message and can create skepticism.

Q: What is the significance of this international struggle against Křetínský, and why is it essential to engage with EPH from multiple countries? How does this contribute to and strengthen the broader movement?

RK: The importance of the international struggle against Křetínský and EPH cannot be overstated. Although Křetínský may be Czech, EPH operates on a multinational scale with a significant presence across various European countries. It’s crucial to recognize that the impact of his business model transcends national borders, necessitating a coordinated effort on a transnational level.

The strength of this approach lies in its ability to connect local struggles and stories into one cohesive narrative. Each country where EPH operates faces unique challenges and issues. However, by uniting under one overarching campaign, we can amplify the message and reveal the common thread running through Křetínský’s activities. This coordinated effort allows us to present the comprehensive story of EPH and Křetínský, which is vital for raising awareness and garnering public support.

Furthermore, the immense power and influence of EPH demands a united front. By working together across borders, the climate movement can pool resources, share strategies, and develop a more effective approach to challenging Křetínský’s business model. Only through such coordination and strategic alignment can we hope to address the formidable challenges posed by EPH and make progress toward a more sustainable and just future.

Thank you very much for this interview!