Nicholas Soo & Zhang Zhongfang, ISF Taiwan

This article was originally published in late April. Since then there were some new developments and events that the article fails to cover, especially in the economy. Nevertheless, the general analysis is valid and gives a picture of the trends at play.

After the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, which ended on October 22, 2022, China has entered a period of greater power centralization. This is reflected in Xi Jinping‘s third re-election as the party leader and in Xi’s appointment of his faction acolytes into the Politburo of the Central Committee, breaking the practice of “Collective Leadership” that prevailed over the past decades. Then in March 2023, during the “Two Sessions” conferences of the Chinese government, in the government reshuffle, important positions were almost completely filled by Xi’s men. This shows a direction of power centralisation in Xi Jinping’s hands.

This concentration of power has very important political implications. It is not just the result of power struggle within Chinese leadership, but also a consequence of developments in the international arena.

In this article, we try to analyze the following questions:

- What is the situation in the CCP with the monopoly of power by one faction after the 20th Congress and the Two Sessions?

- The Chinese economy is recovering from the severe impact of the Covid pandemic. What is the impact for the regime from the White Paper movement and the large-scale outbreak?

- What are the main social problems in China and how do they affect ordinary people?

The Two Sessions and Shifts in the Power Structure

The “Two Sessions” is the event of the annual meetings of both the National People’s Congress (NPC) and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) which meet separately, but at the same time.

At the Two Sessions, in March 2023, it was confirmed that Xi Jinping would be re-elected as the President and the Chairman of the National Military Commission, which broke the precedent for the number of terms that national leaders hold, which was set after Deng Xiaoping.

The new entries in government positions are all Xi Jinping’s “insiders”, except for Wang Huning and Han Zheng, who are traditionally considered members of Jiang Zemin’s faction (also known as the Shanghai Gang). This shows that the power sharing agreements among the different factions, e.g. Jiang’s faction, the Tuanpai(bureaucrats who worked their way up from the Communist Youth League), and the Princelings (descendants of the founding members of the People’s Republic), as the framework for the party politics inside CCP, are now officially over.

Thus -at least on the surface- everyone is now Xi’s man. In addition to this power concentration, the Central Committee members and Congress delegates have also concentrated tremendous wealth. 81 of the delegates have a personal wealth of more than 1 billion US dollars. The CCP is a Party of the wealthy elite in its true sense.

The change in the precedent for the position of Vice-President is also interesting. The practice adopted after Deng Xiaoping is that presidents in their last term will appoint vice-presidentship to the next president of the country. For example, Hu Jintao was the vice president of Jiang Zemin during his second term; Xi Jinping was the vice president of Hu Jintao during his second term. Moreover, the Vice President will also serve an important role in the Party and the People’s Liberation Army (Secretary of the Secretariat of the Central Committee, Vice Chairman of the Central Military Commission) to hone his leadership skills. Contrary to this, the current Vice-President, Han Zheng, is not a close ally of Xi Jinping, was not included in the 20th Politburo Standing Committee, and did not hold any other positions. Therefore, his position has no real power, and apparently, he is not being groomed as a successor. This sends the message that maybe Xi Jinping does not intend to hand over power after his third term.

Some Western media see this as yet another evidence that Xi Jinping has returned to “Maoism” (Guardian). However, we believe that the ultimate goal of these political reforms is to better serve the needs of capitalism in China. The era of Xi Jinping looks very different from the era of Deng Xiaoping and Jiang Zemin, precisely because the development of Chinese capitalism has entered a different stage.

When Deng Xiaoping was building Chinese “state capitalism”, the government needed to reduce its intervention in the market and local governments needed to attract capital investments; however, today, the anarchy of market capitalism and corrupted local bureaucracy has reached its limits. Therefore, Xi Jinping now needs to rein in the anarchy of the market and strengthen the power of the central government as key measures for the CCP to keep control and at the same time keep the economy growing in the next decade.

Xi’s appointment also broke the precedent of the retirement age for high-ranking officials that started during the Jiang Zemin era, which required members of the Standing Committee over the age of 67 to retire. In 2002, Jiang Zemin invented this seemingly arbitrary rule to push out the old guards in the party for the purpose of factional struggle, and now Xi Jinping is breaking the same rule for the same purpose of strengthening his faction. The motives were factional, but arguably the retirement age rule also has the consequence of encouraging renewal at the top layer of the country. It is not yet clear whether Xi Jinping was only breaking this practice for the chief of foreign affairs Wang Yi or whether this will extend to more leadership positions.

The Two Sessions also reiterated the emphasis on “security” of the 20th Party Congress. Its budgets on foreign affairs, military and food production were higher than in the past. This security concern is not accidental, but a response to the US trade war.

With regard to Taiwan, China adopted a somewhat softer stance. One reason is that China is experiencing the most severe economic shock in many years, so the leadership is focusing on the country’s domestic stability. In addition, Wang Huning, the new chairperson of the People’s Political Consultative Conference, the less important of the two congresses, said they have “grasped the strategic initiative for the complete reunification of the motherland.” It is not difficult to understand why the top leaders of China wanted to emphasize that China has the initiative. After the Pelosivisit to Taiwan, the military response has caused widespread fear of war in Taiwan. Taiwan’s 2024 presidential election is increasingly framed as a battle of “war and peace”. Things can go very differently from the plan of Taiwan’s ruling party and the US.

Economy Watch

China’s economic prospects in 2023 have a level of uncertainty. Shrinking exports will deal a blow to its export-oriented economy. China is trying to make up for it by stimulating domestic consumption. But consumer confidence does not appear to have fully recovered yet. Therefore, it is still hard to predict whether China can achieve the official economic goal of recovering from its worst year of the pandemic.

The official target for GDP growth is conservative. The 2023 Government Report set the growth target at “about 5%”, which is slightly lower than the actual GDP growth rate of 6% before the pandemic outbreak in 2019, and slightly lower than the target of 5.5% in 2022.

But compared to the disastrous real growth of 3% of 2022 (when the epidemic in China was at its worst), the Chinese government considers that the worst impact of the pandemic on the economy is over. In March, China’s new Premier Li Qiangexpressed confidence in reaching the growth target.

The shrinking of exports is significant. Since November 2022, China’s exports have shrunk by about 6-10% month over month.

A similar trend is observed in the throughput at the Shanghai Port (FT). It didn’t grow until March this year, and this growth can be regarded as fulfilling the backlogs accumulated over the factory shutdown of last year (NYTimes). Reasons behind this decline include:

- Inflation in advanced economies impacted consumption (CNN. See our article)

- The disruption of the supply chains in late 2022 has not yet been fully restored (CNN, FT)

- The diversion of manufacturing investment caused by the US-China conflict. This is particularly notable in the diversion of Taiwanese capital. Kunshan, the Chinese city with the largest concentration of Taiwanese manufacturers, has experienced a significant unemployment wave (FT). Meanwhile, manufacturing in other countries continues to grow. Foreign capital investment (FDI) in China shows signs of slowing down, indicating that in the face of inflation, China’s pandemic policies, and US-China conflict, foreign capital is hesitant to invest. (SCMP)

(China’s richest county suffers export slump as US tension hits factories, Sun Yu, FT.com)

Compared to exports, China’s domestic consumption shows some positive signs. In January and February, China’s consumption increased by 3.5% from last year; in March, consumption increased by 10.6% from last year (NYTimes).

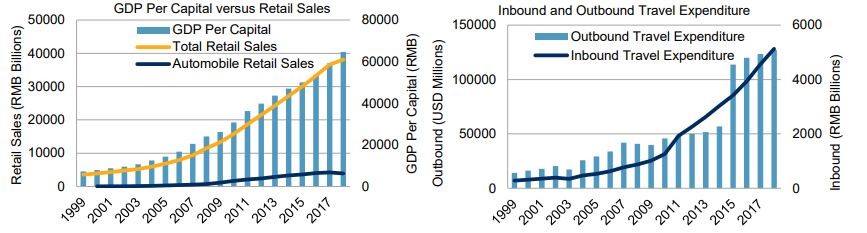

However, short-term consumer confidence is still at a low level, which means that Chinese people tend to deposit their money instead of spending it (Netease). This is not due to inflation, because China’s inflation is the lowest in the world (TradingEconomics). A more likely reason is the fallout from the pandemic, as well as a weakened real estate market that has shrunk the disposable income of some middle-class people who relied on real estate investments for extra income. In the past 10 years, the median disposable income per household in China has grown at an annual rate of 3-5%, which represents the increase in the consumption capacity of the middle class/petite bourgeoisie layers (Statesman). In a longer period, the consumer market in China can be expected to grow in a similar fashion.

(China’s New Economy Sectors: How Are They Doing?, Liyu Zeng et al., 2020, S&P Global)

For a long time, the bulk of Chinese domestic investment went to the real estate sector (China Finance). Thus, the prosperity of the real estate market largely affects the disposable income of the upper middle class. The real estate market showed signs of stabilization in February (Sina Finance). However, some analysts believe that this recovery is temporary (WSJ). After the Evergrande Group bankruptcy in 2021, the Chinese government used the central banking system to keep the real estate companies afloat (NYTimes) to a certain extent, and eased the operating pressure brought by the “three red lines” policies[1]. But at the same time, the Government Report 2023 reiterated the intention to keep houses “for living in, not for speculation”. The government also ordered real estate companies to give priority to completing unfinished projects before starting new ones (NYTimes). This is tantamount to cutting off the business model of some real estate developers in China, as they used the sale of new construction projects to cover the cost of old ones. This will greatly slow down the profit realization cycle in the real estate market, and essentially cool down investment. This spells a decline in the future role of the real estate sector as a major form of domestic investment (Shi Yongqing, Centaline Property), and could cause acquisition of bankrupt developers by bigger ones. This may be unavoidable in the long term, because “the vast movement of rural residents to cities that began in the 1980s has slowed down as villages have been drained of people, while the country’s birth rate has plunged. Oxford Economics estimated that housing demand was 8 million units per year from 2010 through 2019, but would drop to only 4.6 million per year from next year through 2030.” (NYTimes)

China’s recovery is also very uneven. Several consecutive quarters of decline in local government land revenue will further squeeze their fiscal ability to stimulate the economy. This may further widen the disparity between cities and rural areas.

Overall, the proportion of China’s domestic consumption-oriented sector relative to the export-oriented one will gradually increase, but the current economic structure is still fragile and could face turbulence due to internal or external crises, undermining the official growth targets set by the Chinese government.

Developments and Obstacles in Technology Sector

The US-China competition has intensified in the field of technology. China’s investment in R&D is far behind that of the US, but it is growing. The number of companies involved in technology R&D in China is second only to the US, but its total investment in technology R&D is only a third of that of the US (Left Voice).

In some areas, such as 5G telecommunications, AI, and batteries, China is already a world leader and can compete with the US; but in other areas, such as semiconductor design and manufacturing, advanced material, and precision industry, China continues to lag behind. In terms of the trend, this gap is narrowing (Harvard University).

Faced with this situation, the Trump administration carried out various measures to contain China’s technological development, and Biden continues on that path.

On the production side, many Chinese technology companies are put on the “entity list”, prohibiting US companies and even US allies from exporting technology and components to them. In the consumer market field, the US congress conducted an investigation into popular online services in China such as TikTok and levied requirements of data sovereignty on them, while it prohibited certain consumer uses (the most aggressive case is Montana’s blanket TikTok ban). Finally, in the educational field, the US is restricting opportunities for Chinese students to study in the United States (CNN). The pinnacle of this containment strategy is the proposal for the Chips Act (funding to boost US domestic research and manufacturing of semiconductors) and the Chips 4 Alliance (US, Taiwan, South Korea and Japan semiconductor partnership).

The effectiveness of this containment divided the international bourgeoisie. An international discussion has opened up on what should be the direction of such efforts. For example, the CEO of ASML, a Dutch semiconductor equipment manufacturer, Peter Wennink, argued that an embargo on China’s semiconductor technology will end up accelerating the development of their own industry (Bloomberg). A similar argument was made by Bill Gates, who pointed out that the US Chip blockade will only speed up China’s own chip R&D. These arguments may be based on a different strategic vision and/or on the need of these companies to keep their investments and profits in the Chinese markets. In any case, the ruling classes internationally seem divided over this issue, which reflects the fact that they are running out of options.

On artificial intelligence, AI, another critical technical field, some on the Left believe that China is inherently backward in basic science research. They claim that its top-down approach to research limits the freedom of its scientists and that the poverty of Chinese internet content due to censorship and other factors will prevent China’s AI research from catching up with the United States. On the other hand, it is known that results of AI researchers are published as open source in China. Baidu’s ERNIE Bot was made open to the public, and it was considered to have achieved “bearable mediocrity” (WITH). The main difficulty in AI research and practice is not basic knowledge, but computing power and data (Rich Sutton 2019;Julian Togelius et al. 2023). In terms of data, data collection by Chinese companies is considered to have an advantage (heart of the machine). In terms of computing power, China’s supercomputers are already able to compete with the US (TOP500). But there has been a gap in recent years. China’s current most advanced supercomputer, Sunway TaihuLight, was deployed in 2016. The chip embargo could limit the growth of China’s supercomputers (BBC). Their dependence on foreign semiconductor technology casts a shadow on their future. Another noteworthy fact is that the general impression of AI in Chinese society is significantly better than that in Western societies (Ipsos). This could mean less risks of pushbacks from the Chinese public to data collection and commercialization of AI technologies.

The above shows that China faces heavy blockade policies and growth suppression by the US in the field of technology (especially in semiconductors), but this does not mean that China is completely out of the tech race. As we described earlier, some bourgeois analysts have begun to worry that the blockade will accelerate China’s R&D efforts in chip manufacturing, which in turn would limit the blockade effects.

The White Paper movement and the pandemic

China lifted its Zero-Covid policy drastically after the White Paper Movement. The WHO counts 120,000 deaths, but there are unofficial estimates that even talk about 1 to 1.5 million deaths! Western experts claim that if China had prepared sufficient vaccines and medicine, at least 200 to 300 thousand deaths could have been avoided (NYTimes, VOA). Our estimation was that China’s rapid dismantling of the Zero-Covid policy will cause big numbers of avoidable deaths. Zhang Zuofeng, a professor of epidemiology at UCLA (who previously criticized the large-scale testing in Shanghai) also believes that if China adopted an orderly opening up, many deaths could have been avoided. We don’t think the CCP’s drastic opening up is solely due to the White Paper movement, because at least in Zhengzhou there were already signs of this policy U-turn for the economy, at the expense of people’s lives. The White Paper Movement accelerated this process.

At present, the total number of confirmed cases in China (including those who have recovered or died) has exceeded 1 billion. The deaths mainly included the elderly and the poor, which gives the decision to lift the Zero-Covid policy a strong element of social-darwinism. An insider of the Chinese government said “the drastic opening up was hardly a wise public health decision. It was bad timing, and ill prepared”. The impact of the pandemic, with large unemployment in industries such as real estate and education, plus about 10.8 million new graduates seeking jobs, put enormous pressure on the Chinese government to revive its economy, which drove the decision for the drastic opening up. The result, of course, is spikes in cases and deaths.

It can be speculated that the trauma of the pandemic and lockdowns will persist for a long time, even though the society seems reluctant to remember now. However, the U-turn in the pandemic policy and the social crisis that ensued have proved that the Party and Xi Jinping to be not as wise as the propaganda said, and this resentment can resurface and fuel future social movements.

Brewing conflicts in Chinese society

A major social problem caused by the economic slowdown and the pandemic is the high unemployment rate among young people. According to the 2023 Q1 data released by the National Bureau of Statistics, the unemployment rate of people aged 16 to 24 is as high as 19.6% (by comparison, the US Bureau of Labor Statistics announced an unemployment rate of only 8.5% in summer 2022). Meanwhile, the unemployment rate for workers aged 25 to 59 was just 4.9 percent.

This means there has not been an overall cutting of jobs, and also there are not a large number of suitable new graduate’s jobs created. In the end of 2022, a report noted a shortage of workers in the manufacturing industry due to the lifting of Zero-Covid policies, but this obviously does not solve the overall unemployment problem of young people in China (FT, economic daily). Facing high unemployment rates, Chinese young people reacted in various ways: Some postponed their graduation; some sought to become public servants by taking the relevant examination; or simply adopted the attitude of “laying flat”.

Beginning in 2023, a wave of self-deprecating remarks and memes based on Lu Xun‘s fictitious character Kong Yiji appeared on the Internet in China. Kong Yiji was depicted as an intellectual who failed in the imperial exam. The Chinese youths used his character to express the anxiety of their predicament where upon graduation one can’t find a job matching their education, and yet can’t bring themselves to jobs that are “below them”. The state media published several editorials commenting on the phenomenon, trying to quell the youth’s anxiety about unemployment, pointing out the support of national policies for young people, and so on. But from an official point of view, trying to attribute the problem to “personal motivations and personal efforts” certainly does not resonate with young people.

Because the policy to promote higher education continues, the number of college graduates in China is still increasing (Zhihu). China’s “gaokao” (National College Entrance Examination) participants reached a maximum in 2021, after which the admission rate declined (Higher education analysis). Therefore, the number of college graduates in China will reach its maximum sometime after 2025. This is one of the reasons behind the failure of many graduates to find a job, that is, the number of fresh graduates is still increasing while the economy is slowing down and unable to quickly create a large number of new jobs. Education analysts believe that the decline in the admission rate in 2022 represents a shift in education policies towards “vigorously cultivating vocational education”. This could mean the Chinese government had predicted the change in the composition of new jobs in 2022.

The pandemic exacerbated the already competitive youth labour market. Graduates from first-tier cities are less prone to unemployment, but young people in second- and third-tier cities have indeed suffered a huge impact. This shows another urban-rural difference in the job market, and that could exacerbate the urban-rural wealth gap (Taiwan’s Mainland Affair Committee investigation). On this basis, it is not difficult for us to understand why many Chinese youths choose to “lay flat”.

On the other hand, the problem of the declining birth rate is very deep in China, but its impact is revealed slowly. In 2023, China’s population will decrease for the first time since 1962, five years earlier than the official estimate (China Net, China News Weekly).

Judging from the experiences of South Korea, Japan, Taiwan and other neighbors, the prospect for China’s population is pessimistic. The South Korean government tried reforms and welfare policies within the framework of capitalism, but none of them have increased the birth rate (of course, it is possible that without these subsidies, its birth rate could have declined more). This shows that young people are not willing to have children in the current environment of high social and economic pressures. At the same time, the degree of aging in Chinese society is not yet comparable to other industrially developed nations, the population over 65 years old accounts for about 15% (National Bureau of Statistics of China), which is still far behind Japan’s 29% (Foresight). However, if China’s economy does not improve significantly, it will still be difficult to reverse the problems of declining birth rate and aging. Although the Chinese government introduced the “three-child policy” in 2021, allowing up to three children per household, a poll made by Xinhua among 32,000 Weibo users found more than 29,000 of them still “have no plan of having children” (NYTimes).

China’s declining birth rate is closely related to the issue of women’s rights. A report points out that even when the Chinese government implemented the two-child policy in 2016, many women were asked about their plan to have children when applying for jobs; some were forced to sign a “promise of non-pregnancy” that would lead to their dismissal if they became pregnant. In recent years, inspired by the international MeToo movement, a feminist consciousness has been developing at the grassroots level. Feminist discourse is still relatively easy to be had under China’s Internet censorship, but like other social movements, they are also being suppressed. For example, after the White Paper Movement, the government detained four women’s right advocates for “provoking troubles”. The Wall Street Journal reported more than 20 arrests made in Beijing after the movement, most of which were women. However, this suppression of women activists has not changed the determination of Chinese feminists fighting against gender inequality, for democratic rights and resisting the CCP dictatorship. Many reports highlighted the militancy of female protestors during the White Paper Movement (VoA, Initium).

The protest of Chongqing workers also deserves some attention. The lifting of Zero-Covid policy impacted different sectors in different ways. When the Chinese government stopped conducting mass testing, the business of test kits plummeted. In January, a pharmaceutical factory making test kits in Chongqing fired 8,000 workers without consultation in order to cut its losses, triggering mass protests. Nearly 20,000 workers took to the streets. At some point the angry workers even forced back the police.

Conclusion

From the 20th Party Congress to the Two Sessions, China is moving in a direction of increasing authoritarianism under Xi Jinping. The apparent calmness cannot conceal the violent instability hidden within Chinese society.

The scale of recent social movements is very small compared to its huge population. But with correct leadership and organization, these movements may still have potential to expand and challenge the rule of the CCP.

In the intensifying US-China conflict, the US is worried about China’s development and is driven towards more blockades and trade wars. The Xi Jinping regime plays up foreign threats to distract from social contradictions domestically, but as we have seen, problems in the economy, repression of women’s and worker’s rights, youth unemployment, ect, are adding cracks to the official narrative. We believe that in the future, more grassroots groups will see through the lies of Chinese state capitalism and realize the importance of a Chinese revolution.

Many young people are now interested in the ideas of Marxism, and many new left-wing spaces have sprung up on the internet, inside and outside the Great Firewall. As internationalists, we are eager to have dialogues and learn from and exchange experiences and views with Chinese left-wing activists. Because China’s future, whatever it may be, will have a profound impact on the whole planet.

For the people of Taiwan, Hong Kong and Macau particularly, unity with the working class in China, in order to challenge the CCP, the world’s largest “corporate party”, and kick off the prelude to building a democratic socialist world, is crucial.

[1] The “three red lines” policies refer to three regulation policies that the Chinese government introduced in 2020 to limit the amount of loan and debt for real estate developers. This was said to have contributed to the bankruptcy of Evergrande due to a financial crunch.