On August 24, GAS (the ISp affiliate in Romania) held two lectures at a public event organized in Bucharest. This is the slightly edited text that formed the basis of one of the presentations.

The war on public education

One of the most absurd consequences of the austerity measures taken by the Bolojan government is the assault on the education system. It is clear from the outset that such measures are in the immediate interest of capitalists: money that would go to working-class youth and employees will, in one form or another, end up in the pockets of those who are already rich. Whether it is a matter of preserving tax privileges, embezzling through public procurement, or literally purchasing weapons, the rich will get richer and the poor will get poorer.

What is strange is that the savings are not that great, so the “marginal utility” for capital is positive, but negligible, while for workers it is negative and very high. The Fiscal Council analyzed the measures taken by Daniel David and concluded that, far from the three billion promised by the minister in early June, “in 2025, these measures may lead to a reduction in budget expenditures of about 0.02% of GDP,” or 378 million lei. Even if the initial figure had been accurate, the budget deficit for 2024 was 9.28% of GDP, or 163 billion lei. Is it worth cutting education in order to make savings that, even in the most optimistic projections, are still a drop in the bucket?

Of course, austerity also has the indirect effect of enriching those who are already rich, as can be inferred from David’s response to student representatives, whom he urges to take part-time jobs to make up for lost scholarships. Increasing the supply of labor will, in principle, put downward pressure on wages, which will again lead to savings for the capitalist class.

However, even this prospect is limited, as in the medium and long term, capitalists need, on the one hand, a skilled workforce to integrate as high as possible into the value chains and own the most profitable businesses, and on the other hand, a relatively literate and disciplined population. As the leaders of the three largest trade union federations say in a joint open letter: “the underfunding of research institutions, in the current European geopolitical context, by failing to update the costs necessary for human resources and utilities, for the maintenance and development of infrastructure, institutions of particular importance for the proper functioning of education and research [will lead to an unprecedented crisis in the education system].” Note the use of the term “human resources” in the appeal.

This is the cruel irony of the situation, that workers’ organizations, instead of fighting at least for the welfare of the employees they represent, if not for the entire working class itself and against capital, have to explain to capitalists how a better-educated population is to everyone’s advantage, including and especially the economic elites. The absurdity reaches unimaginable heights when even mainstream, bourgeois experts say such things. And they have been doing so for a long time. For example, in 2020, the rector of Babeş Bolyai University (Daniel David, the current Minister of Education) explained on his blog that: “we need (1) more higher education graduates (especially bachelor’s/master’s degrees), (2) an increased number of academic staff, and (3) an increase in funding. Of course, that is if we want to be a modern, knowledge-based society, not a scientific/technological colony.” If Daniel David does not listen to Hăncescu, Nistor, and Hadăr, he could still listen to experts such as… Daniel David.

In general, we may believe that capitalists are foolish, that they only know their immediate interests and thus cut the branch they are sitting on, cushioning their fall on our backs. This is not the case here, as David has a fairly long history of relatively sensible statements, demonstrating at least an understanding of the need to develop ‘human capital’. The situation David finds himself in is therefore quite interesting, as it points to a deeper source of the problem than a simple conspiracy of power. Why did an intelligent man who, even from the managerial perspective of the rector of a large university, affirmed the profitability of investments in education for harmonising the interests of capital with those of employees, but also of the general population, change his perspective so abruptly? And why is it that he, of all people, found himself at the helm of this particularly aggressive assault on the public education system? One reason is that his corporate vision of harmonising the interests of capital and labour in an enterprise collapses when, from his ministerial chair, he looks at things from the point of view of the collective Romanian capitalist. At such a level, the contradiction between capital and labour can no longer be resolved.

Things can be viewed from two perspectives. One would be that of the imperialist system, which imposes a social division of the world where different national capitals are centralised in the large metropolitan centres where the value produced in the peripheries and semi-peripheries is accumulated. However, we cannot understand this division of the world without understanding the technical division of labour. That is why we will go down to the level of production and show how, from the outset, the working class is placed in an inevitable conflict with the capitalist class and how this conflict has ramifications at the level of the organisation of education. Here we must take a plunge into an elementary, but somewhat philosophical, sphere of political economy criticism.

How did education become a commodity?

Capitalism is a society where the production of commodities is generalized. In 1848, Marx wrote that there was no longer ‘any connection between man and man except naked interest, except the merciless “cash payment”’. He was not, of course, speaking as a matter of fact about a world where slavery still existed across the American continent, serfdom still existed in Eastern Europe and parts of Central Europe, where most European states were still monarchies, and where Asian states were bureaucratic empires.

Marx was talking about the fundamental logic of the capitalist mode of production, built around the commodity form. In this logic, any human activity, in order to be recognised as socially important and for its relative importance to be assessed, will be transformed into a commodity, and as such, any citizen who works for a living will become a worker. If we understand the division between intellectual and manual labour as the division between planning and supervisory work and execution work, it becomes much easier to accept that the condition of worker does not arise from the active organ in the work process, but from the placement of the worker in a technical division of labour whose purpose is the production of commodities which, through sale, will generate profit for the employer. That is why Marx had no difficulty imagining a school organised like a factory, even before such schooling systems became widespread:

“If we may take an example from outside the sphere of production of material objects, a schoolmaster is a productive labourer when, in addition to belabouring the heads of his scholars, he works like a horse to enrich the school proprietor. That the latter has laid out his capital in a teaching factory, instead of in a sausage factory, does not alter the relation.” (Capital Vol. 1 p. 614)

The reason why such generalised commodification can take place is that any good or service results from human productive activities, i.e. from labour. At first glance, the proposal is absurd, because the work of a teacher cannot be compared to that of a technician, a truck driver or a labourer. David Ricardo attempts to resolve this issue by proposing that any good can be understood as a composition of different quantities of qualitatively different types of labour, whose correct prices have been established over time on the market. Ricardo was satisfied with this explanation in part because, unlike Adam Smith before him and Karl Marx after him, he was almost entirely unconcerned with the actual process of labour in enterprises. But his solution only works locally and for a relatively short period of time. It ultimately fails because professions appear and disappear or change character depending on changes in the work process, and the wealth of goods that surround us does not necessarily reflect a similar wealth of professions. On the contrary, artificial intelligence, for example, threatens to wipe out all kinds of jobs without reducing the supply on the market, at most only us. The reason why technology, and as such the labor market, is evolving in this way is also the reason why the value of a commodity can, however, be reduced to the labor time required to produce it.

Marx’s solution for the social substance of value starts from the observation that “however varied useful labor or productive activities may be, it is a physiological truth that they are functions of the human organism, and that each of these functions, regardless of its content and form, is essentially an expenditure of the human brain, nerves, muscles, and sense organs” (Capital, Vol. 1, p. 86, emphasis added). From a social point of view, all that matters is that for a certain period of time someone has used, in whatever configuration and combination necessary for that activity, their brain, nerves, muscles, and sense organs, which ultimately allows the reduction of an hour of work by a teacher, technician, truck driver, or laborer to a certain amount of abstract labor time.

Of course, at any given moment, it is not only difficult to assess how much abstract work goes into an hour of work in a particular occupation, but from a certain point of view it is not even very relevant, because two laborers cannot teach a teacher’s class, and four laborers cannot perform a medical consultation. But what if they could?

But what if they could?

This “but what if they could” has been recognized since Adam Smith as the secret of capitalist production.

Before capitalist production, any craft or profession functioned as a homogeneous activity, often acquired over time after a long apprenticeship or at least as a family occupation, and which was performed according to “old wives’ rules,” but especially according to intuitions developed on the basis of experience. These professions also had a high degree of versatility, with craftsmen being able to perform a whole range of operations.

The Scottish economist observes how homogeneous work processes are studied in order to be broken down into smaller steps that workers can more easily specialize in by developing their own skills or using specialized tools, thereby saving time that would otherwise be lost in switching from one task to another. Charles Babbage later develops the analysis of the technical division of labor by observing how “by dividing the work to be performed into different processes, each requiring different degrees of skill or strength, the master manufacturer can acquire exactly the precise amount of both that is necessary for each process. In contrast, if the entire work were to be performed by a single worker, that person would have to possess sufficient skill to perform the most difficult tasks and sufficient strength to perform the most laborious of those operations into which the art is divided.”

An integrated craft thus becomes transformed into a complex activity that can be expressed as a composition of simple tasks that are much easier for anyone to perform without much training. Even when a particular task cannot yet be broken down into a system of simple tasks, the skilled worker can only perform that activity, reducing the need for such professionals. From the point of view of capitalist social wealth, this reorganization of production is beneficial, expanding both the range and volume of goods available to us. For workers, however, Adam Smith himself tells us what the consequence is:

“The man who has spent his whole life performing a few simple operations, the effects of which are probably always the same or nearly the same, has no opportunity to exercise his faculty of knowledge or to exercise his inventiveness in finding practical solutions to difficulties, if these difficulties never arise. He will naturally lose the habit of exercising them and, in general, will become as stupid and ignorant as a human creature can become. The dullness of his mind will render him not only incapable of enjoying or taking part in rational conversation, but also of conceiving anything generous or noble, of having tender feelings, and consequently of forming any fair judgment concerning many of the ordinary duties of his private life. He is wholly incapable of judging the great and extensive interests of his country, and unless someone takes the trouble to do something to change this, he will be equally incapable of defending his country in war. The uniformity of his civil life will naturally corrupt his courage of mind and make him look with aversion upon the irregular, uncertain, and adventurous life of the soldier. It will even corrupt his bodily activities, making him incapable of exercising his strength with vigor and perseverance in any occupation other than that for which he has been trained. The skill with which he performs his job thus seems to have been obtained at the expense of his intellectual, social, and martial virtues.” (The Wealth of Nations 382)

Responding to this problem, which he identifies so vividly, Smith prescribes public education, but, as Marx characterized the proposal, in homeopathic doses. Let us note how concerned Smith is that, deprived of education and brutalized by work, the common man no longer respects his obligations to the state, such as going to war, nor will he be able to find another job, his labor power thus unable to be a source of abstract labor. There are few Marxist texts that satisfactorily describe the importance of the public education system in training citizens first and foremost as subjects of the capitalist state, literate only enough to be able to follow its laws, consume goods, and provide abstract labor throughout their lives. but the need for such an institution can be seen as early as Smith, and also in this passage where Marx discusses the effect of the loss of skilled labor in printing shops:

“In English printing shops, for example, it was once the practice to move apprentices from lighter to more complex tasks, a transition that corresponded to the system of old manufacturing and crafts. They went through the entire apprenticeship until they became printers. Literacy was a prerequisite for everyone to practice the trade. All this changed with the introduction of the printing press. It is operated by two categories of workers: an adult worker, who supervises the machine, and a number of boys, usually between the ages of 11 and 17, whose sole occupation is to feed the paper into the machine or remove the printed sheets. They perform this drudgery, especially in London, for 14, 15, or 16 hours without interruption several days a week and often for 36 hours straight, with only two hours for meals and sleep! Most of them cannot read and are, as a rule, completely wild and abnormal creatures.

As soon as they become too old for this childish work, that is, at most 17 years old, they are dismissed from the printing house. They become recruits for crime. Several attempts to find them work elsewhere have failed because of their ignorance, brutality, and physical and intellectual decline.” (Capital Vol. 1 p. 493-4)

In addition to minimal literacy and long discipline, which initially masks youth unemployment and subsequently prevents them from joining the lumpenproletariat, but keeps them in the industrial reserve army, Smith gives school an implicit role. The Scottish thinker saw no point in teaching simple people Latin—the language of scholars, diplomats, doctors, lawyers, and philosophers. If schools are to teach the children of ordinary people something more than arithmetic or reading and writing in the vernacular, then they must teach them “some elementary geometry and mechanics” because “there is no ordinary trade in which there are not some opportunities for applying the principles” of these disciplines. Public education thus has the role of making jobs that would otherwise have been considered skilled become semi-skilled or even unskilled by generalising the skills needed by industry at the expense of society as a whole.

Even though the role of the education system is primarily to reproduce the capitalist system and is a relatively expensive system, the costs of schooling are borne by workers through taxes, school fees, or the supplementation of public education with private tutoring, optional textbooks, and as the need for those technical skills decreases with the saturation of the labor market or the development of technical division in areas where skilled labor was once needed, the expense is borne mainly by workers. Ultimately, when the skilled professions for which schools prepare young people are almost broken down into simple tasks by technical means, the budget dedicated to education cannot help but appear to be wasted on keeping teachers and students away from the labor market.

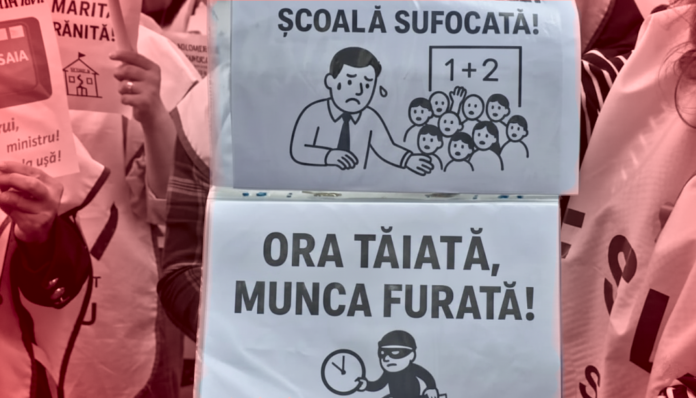

In the context of saturated labor markets and the loss of skills through digitization, and now through automation with artificial intelligence, public education is, from the capitalists’ point of view, a waste of money and time when, for 3-5 years, hundreds of thousands of teachers teach hundreds of thousands of students only for them to occupy the same jobs as young people without higher education completed or even started. How many billions of hours of abstract human labor have been wasted! Putting it this way explains the cutting of scholarships, the merging of classes, the increase in teaching hours, the reorganization of jobs so that tens of thousands of substitute teachers are left without work, and thousands of pupils and tens of thousands of students are left without the scholarships that allowed them to devote themselves entirely to their education.

Are we giving capital what it wants?

However, the struggle is not only about surplus value. While education is under attack almost everywhere in the world, military spending, which is also unproductive, is increasing. The reason for this is the necessarily contradictory nature of public education. Since Adam Smith, the public education system has been financed with homeopathic stinginess because capitalists recognize that the educated common man will not only enjoy a rational discussion with his employer, accepting his reasoning, but will also challenge it. In fact, educated ordinary people will enjoy rational discussions among themselves, discovering their own rationality, within which they will be able to conceive of generous and noble actions, but not diligent work for their boss, paying taxes, and going to war, but solidarity with other workers and other oppressed peoples. Capitalists recognize that educated ordinary people will not limit themselves to a little geometry, mechanics, electrical engineering, and programming, just enough to be able to work in workshops and laboratories until they are replaced by the technical division of labor, but will want to know fundamental mathematics and physics, history and political economy, and medicine, and will educate each other. That is why reading Marx in the spirit of the working-class tradition of self-education is threatening to the bourgeois state, as the Masch group in Germany discovered at the beginning of the year.

That by performing simple, routine, specialized work, man “becomes as stupid and ignorant as a human creature can be” is only a coincidence. But it is a fact that capital constantly exploits so that our exploitation is felt as nothing more than a stupid cry, so that we do not conceive of a better world together and, above all, so that we do not build it using the tools that capital itself has placed in our hands.