In the late 1920s, Nigeria was firmly under British colonial rule, administered through the system of indirect rule that governed vast territories with minimal European personnel. Colonial administration relied on warrant chiefs appointed by the colonial rulers, who exercised judicial, fiscal, and executive powers and were accountable upward to colonial officers and not downward to local populations. The colonial economy was oriented toward the extraction of agricultural produce and the generation of tax revenue to finance administration, policing, and infrastructure serving imperial interests.

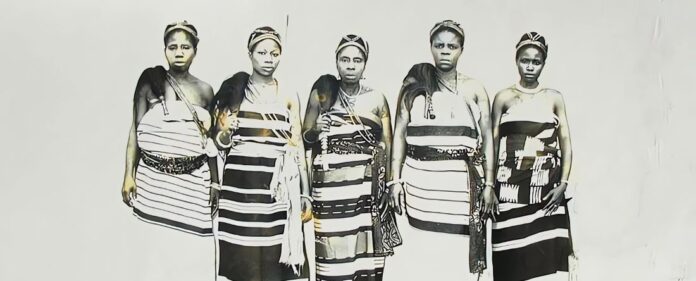

In December 1929, the Aba Women’s Riots—also known as the Women’s War—erupted across large parts of present-day south-east Nigeria. The protests included women from six ethnic groups (Igbo, Ibibio, Andoni, Ogoni, Efik, and Ijaw). The immediate trigger was the attempt by colonial authorities to organise a census, with the aim of extending direct taxation to women (in 1928 direct taxation was imposed on men, but they were paid by the whole of the family). Tens of thousands of women mobilised, using traditional forms of protest such as “sitting in” (surrounding) officials’ homes and offices, following warrant chiefs wherever they went and expressing their anger, targeting native courts and colonial administrative centres, etc. Markets were shut down, roads blocked, and court buildings attacked or destroyed, effectively paralysing colonial administration for weeks. British forces responded with armed repression; troops opened fire on unarmed protesters in several towns, killing over 50 women and wounding many more. Despite the violence, the uprising forced the colonial government to abandon plans to tax women and initiated limited reforms to the system of indirect rule. The events exposed the fragility of colonial authority and demonstrated the capacity of working women to organise mass resistance.

In this article, Deborah Eli Yusuf (Tinam) explores the lessons from this struggle and draws comparisons for today’s movements.

The Aba Women’s Riots of 1929, also known as the Aba Women’s War, were a major mass protest by women against British colonial rule in southeastern Nigeria. The uprising took place mainly in Aba and surrounding areas of present-day Abia State.

The protests began in Oloko, near Aba, after a woman named Nwanyeruwa was questioned by a colonial agent. She alerted other women, triggering a rapid mobilisation. Within days, thousands of women gathered to protest, marching through towns, singing protest songs, and surrounding native courts and the homes of warrant chiefs. Their demands focused on stopping the taxation of women and removing corrupt local authorities. Over the course of the two-month “war,” at least 25,000 Igbo women participated in coordinated actions against British officials.

Large numbers of women converged on Native Administration centres in Calabar and Owerri, as well as in smaller towns, protesting both the warrant chiefs and the taxes imposed on market women. They employed the traditional method of public shaming known as “sitting on a man,” involving all-night song, dance, and ridicule. In several cases, this tactic forced warrant chiefs to resign.

The protests escalated into direct attacks on symbols of colonial power. European-owned stores and Barclays Bank were targeted, prisons were broken into and prisoners freed, and many Native Courts were destroyed by fire. In response, colonial police and troops were deployed. They opened fire on crowds in Calabar and Owerri, killing more than 50 women and wounding dozens more.

Among the protesters was Adiaha Adam Udo Udoma, who seized a British officer’s rifle and broke it in an act that became a powerful symbol of defiance. By the end of the uprising, at least 50 women, including Udoma, had been killed, and many more injured. Despite the brutal repression, the movement endured.

The protests ultimately forced concessions from the colonial authorities. Plans to tax women were abandoned, and several warrant chiefs were removed from office.

***

The Aba Women’s Riots of 1929 remain one of the most powerful demonstrations of Nigerian women’s collective resistance. Thousands of women—market women, farmers, traders, and mothers—mobilised across districts in the then Eastern Nigeria to challenge colonial taxation and the extension of warrant chiefs’ authority over their lives. They organised without formal structures and without institutional support. And yet, they achieved national disruption and forced policy change. When we contrast that era with the landscape of women’s movements today, the differences reveal both how far we have come and what we may have forgotten.

The Aba Women’s Riots were not only a gendered uprising but also a class struggle rooted in the economic exploitation and social restructuring imposed by colonial capitalism. A socialist point of view helps to reveal how colonial rule reshaped relations of production and imposed new class hierarchies that women directly resisted.

Before British rule, many Igbo and Ibibio societies were relatively flexible in terms of gender roles. Women played central roles in local economies—through agriculture, trade, and cooperative labour (such as the umuada and mikiri networks). The umuada consisted of women born into a lineage or village who could intervene in disputes, sanction antisocial behaviour, organise collective protests, and enforce community norms through social pressure and ritualised actions. The mikiri (also known as women’s meetings or associations) were regular assemblies of married women within a community. These networks coordinated economic activity—such as market regulation, collective labour, and mutual aid—and served as forums for political discussion and mobilisation.

British indirect rule dismantled these structures and replaced them with male warrant chiefs, male tax officials, male-controlled courts, and the exclusion of women from any form of decision-making. This represented a patriarchal restructuring of society, in which the colonial state elevated men—especially those who collaborated as local agents of imperial power. Colonialism did not simply exploit labour; it reorganised gender relations in ways that made women’s labour easier to extract and less politically defended.

Thus, the British colonial rule, contrary to the false claim that it helped “democratise” countries or “liberate” women, imposed a system that elevated patriarchy to new heights, so as to serve its interests.

***

One of the first challenges the Aba women faced—one that is no longer as present today—was the complete absence of political recognition. Women at the time were excluded from formal governance; they were not seen as political actors and did not vote (men acquired voting rights earlier than women, although also under restrictions). Their mobilisation first had to assert their political personhood before demanding anything else. Today, Nigerian women still face underrepresentation, but they are at least acknowledged participants in political discourse. Policies, ministries, gender desks, and advocacy platforms exist, even if imperfectly, and women can push for reforms through both formal and grassroots channels.

Another challenge that women in 1929 had to navigate was communication across vast distances without literacy or technology. They relied on networks, songs, messengers, and market alliances to coordinate action. Today’s organisers benefit from social media, digital advocacy, and rapid mobilisation tools that reduce logistical barriers and amplify voices far beyond local communities.

***

There are enduring lessons in the way the Aba women mobilised. Their movement was deeply community-rooted; they were not elites speaking on behalf of the masses—they were the masses. Their power came from collective legitimacy, a shared grievance, and a clear strategy that everyone understood. They also practiced what was essentially feminist organising: solidarity across clans, a refusal to centre individual leaders, and a commitment to nonviolence—until they faced violent repression by colonial forces. Modern movements sometimes struggle with fragmentation, internal rivalry, and the pressure to elevate individual faces rather than collective goals.

In many ways, today’s women’s movements also struggle under the weight of constant “activist trainings”, frameworks, and Western-influenced bourgeois toolkits that can dilute the very agency they are meant to strengthen. Activism has gradually become “professionalised,” and while capacity-building has its place, it can unintentionally create dependence on external validation before women feel confident enough to act. The Aba women did not wait for workshops on movement-building, advocacy strategy, or leadership; they mobilised because the urgency of their lived experience demanded it. Their power was organic, instinctive, and rooted in shared realities. When modern movements become overly shaped by imported bourgeois methodologies, they risk losing that raw, community-driven energy that once made women’s uprisings so transformative.

***

Unlike in 1929, contemporary advocacy now leans heavily on digital spaces, which can distance organisers from rural women whose realities mirror those of the 1929 protesters more than those of urban inhabitants. For example, NGO debates on gender equality frequently centre urban issues—career mobility, political appointments, digital violence—while rural women still grapple with land rights, market taxation, displacement, and insecure livelihoods. Earlier movements would likely have pushed for deeper integration of rural women’s priorities, since their strength came from women who understood each other’s economic struggles firsthand. Another gap is sustainability. Many modern protests surge in moments of crisis but lose momentum afterwards. The Aba women maintained long-term pressure because their grievances were tied to everyday survival; they did not have the luxury of moving on. Their consistency and clarity offer a model for building movements that do not fade once headlines end.

Ultimately, if modern women’s movements in Nigeria are to reclaim their power, they must return to the grassroots, where realities are raw, urgent, and unfiltered. Rural women, who often carry the heaviest burdens, should not be an afterthought; they should be the starting point. And while international support has played a role in pushing gender issues forward, movements should not be dependent on it. The Women’s War of 1929 illustrates how colonial capitalism relied on patriarchy to function, and how women’s oppression was foundational to the colonial economy.

***

Too many actions today feel cosmetic—grand displays without the heat of real rage or the conviction to disrupt the system in a meaningful way. To move beyond this, organising must be bold, provocative, and grounded in lived experience. Only then can women’s movements break free from inherited templates and reclaim the fearless, self-determined spirit that once defined women’s resistance in this country. This is the way to place themselves at the forefront of the struggle to dismantle capitalism and patriarchy and establish an egalitarian socialist society.

Deborah Eli Yusuf (Tinam)

Deborah, also known as Tinam, is a development worker, political commentator, and political economy and history enthusiast working at the intersection of peacebuilding, gender equality, and governance. She holds a Master’s degree in International Affairs and Strategic Studies from the Nigerian Defence Academy and has a background in Journalism from Ahmadu Bello University. She is a member of the Revolutionary Socialist Movement