This is a part of a series of articles. Read the intro here, part I here and part II here

For a period in the early 1990s we mobilised simultaneously against sectarian attacks and intimidation, against racism and antisemitism, in defence of women’s reproductive rights and the establishment of the Brook Advisory Centre, and for the rights of gay and lesbian people. This work took place in years marked by intense violence and political turmoil during which comrades in Militant provided a lead on multiple occasions, organising strikes and protests against sectarian paramilitary groups, and campaigning against state repression.

In this article, we explain the launch of Youth Against Sectarianism on the 29th of February 1992 in the aftermath of the Teebane and Ormeau Road Bookies massacres. We describe the exemplary work that we then sustained over the following four years. Youth Against Sectarianism (YAS) was affiliated to Youth Against Racism in Europe (YRE), an international initiative of the Committee for a Workers International and we mobilised young people to the major YRE mobilizations in London, Brussels and Germany.

On the Edge of Armageddon

In the period 1992-1993 there was a sense of events spiralling out of control. On January 17th, 1992, an IRA landmine killed eight Protestant men and wounded six others at Teebane Crossroads near Cookstown, County Tyrone. The men had been working for the British Army at a base in Omagh and were returning home in a minibus. According to the IRA they were legitimate targets because they had been “collaborating” with the “forces of occupation”.

Catholic communities waited in fear for the inevitable retaliation. There were multiple shootings across the next two weeks, and everyone knew a major attack would come. In two days in early February nine died in Belfast shootings. On February 4th an off-duty RUC officer, reportedly distraught after the killing of a colleague, walked into a Belfast Sinn Féin office and shot dead two Sinn Féin activists, and a man who had come into the office to ask for advice. The attacker then drove away from the scene and shot himself.

On February 5th the Ulster Defence Association (UDA), using the cover name “Ulster Freedom Fighters” (UFF), launched a gun attack on a bookmaker’s (gambling) shop on Lower Ormeau Road in Belfast. Five Catholic men and boys were killed and nine wounded. The youngest was only 15. The atrocity was claimed as retaliation for the Teebane bombing. Noone expected this to be the end. The North seemed to be spiralling deeper and deeper into conflict.

The only force with the capability of stepping into this developing maelstrom was the organised working class. An independent class lead was necessary. Three years earlier, on 9th March 1989, the Mid-Ulster Trades Union Council (a local body bringing together trade union branches from multiple unions), which was led by Militant members, called a local one-hour protest strike in the Magherafelt and Cookstown areas after the IRA killed three Protestants in a gun attack at a garage in Coagh. This attack came after a series of killings by Loyalist paramilitaries (in favour of the connection with Britain) in the area and tensions were high. Hundreds of Catholics and Protestants walked out together at Unipork in Cookstown (a pork processing factory where a Militant member was the deputy convenor). There were also walkouts from shirt factories, a timber yard, and the Mid-Ulster Hospital. The Irish Congress of Trade Unions ignored this stand, but the idea of trade union organised, area-wide protests and strikes had been firmly re-established (the last such mobilisations had occurred in January 1976).

Knowing when to act, and how to organise, is of fundamental importance. In January 1992 the Mid-Ulster Trades Council called a second strike after the Teebane killings. The secretary of the Northern Ireland Committee of the Irish Congress of Trade Unions (NIC-ICTU), Terry Carlin, went to great lengths to dissociate himself from the strike on radio, TV and in the press, claiming that the Trades Council had no official status. Amid a storm of protest, he had to back down and ended up by addressing the Trades Council rallies in Magherafelt and Cookstown.

After the Ormeau bookies attack, Militant members moved a motion for action at Belfast Trades Council. The example of Mid-Ulster forced the hand of the trade union leaders who responded by calling an evening protest of several thousand at the Ormeau bridge and a lunchtime rally of 20,000 in Belfast city centre several days later.

The struggle against sectarianism can be likened to a war of manoeuvre, with the forces of reaction ranged against the power of the working class. This power is most often latent, expressed in the passive but very real resistance which prevents sectarian forces escalating their activities. At key junctures the power of the working class became manifest and the paramilitaries, the naked face of sectarianism, were stopped in their tracks, or even pushed back for a period of time.

February 1992: Launching Youth Against Sectarianism

Militant recognised the widespread opposition to sectarianism among young people and, taking a bold initiative through the Young Socialists, launched Youth Against Sectarianism (YAS) in February 1992.

“Youth Against sectarianism was born out of the tremendous anti sectarian trade union demonstrations of 1992. Youth not organized before against the bigots needed a voice immediately and YAS was established. Since that time, the general anti sectarian mood of young people has increased. Teenagers today do not want another 25 years of the same upheaval, conflict, state injustice and a hopeless economic future.[1]

YAS was initiated in Newry where we had members in a local school, including key organiser Patrick Dageenar. We noted “the launch of the YAS has got off to great start. The Newry organized two meetings of school students with 35 and 60 present. Over 40 have already joined the new group. A school rally has been planned for March the 19th in the town centre… Saturday, 14th of March sees a day of action in Newry Town Centre”.[2]

The rally was a success: “A public rally of 200 Catholic and Protestant youth in Newry in March 1992 was our first big event. Big meetings of between 50 and 100 took place in the same town and others like Downpatrick and Bangor. YAS groups quickly established themselves in many areas, including Ballymena, Omagh and Cookstown, as well as east, west, north and south, Belfast and Derry City. Our YAS bulletins have sold in the 1000s and bring new ideas and areas alive to our radical fighting ideas”.[3]

On March 25th, 1992, the National Union of Students held an anti-sectarian march and rally in Belfast which attracted several thousand university students. Militant student comrades intervened to ensure that the event would be more than a “peace” day of action and would also address the underlying issues of poverty and unemployment which helped to fuel the violence-in other words we ensured that class issues were to the fore, not just an abstract desire for an end to the violence. As we explained “YAS groups bring Catholic and Protestant youth together and discuss the issues lie at the heart of sectarianism, such as unemployment and social deprivation”.[4] We organised a YAS contingent on the march.

Students at one school, Grosvenor High School in Belfast, spontaneously organised their own protest on March 31st. Again, we organised a YAS contingent and afterwards, we held a YAS public meeting. In the coming months YAS attracted hundreds to dozens of meetings, rallies, and gigs across the North.

A YAS “Rock Against Sectarianism” festival was held in Belfast on April 2nd, and several hundred teenagers attended the (alcohol-free) event. This was the first of many gigs. One of the bands who played at a YAS gig was Ash, then an up-and-coming group from Downpatrick but who later found fame. They name-checked YAS in an interview in the New Musical Express (then a prominent outlet in Britain and Ireland) some years later, when they explained that the festival had provided them with their first stage outside their hometown.

The first Youth Against Sectarianism conference was held on the 27th/28th June 1992. YAS members attended from Belfast, Newry, Derry, Cookstown, Omagh, Ballymena and other areas. There were discussions on fighting racism, sectarianism and bigotry, and on youth rights. Guest speakers included Andrea Enisouh[5][6] from Youth Against Racism in Europe (YRE), and Clare Daly, on behalf Dublin Youth Rights Campaign. A steering committee was elected.

Activities continued over the summer of 1992: on 11th of July, Mid-Ulster comrades and several new YAS members sold over 50 YAS bulletins in Magherafelt Town Centre. Also, in July, YAS bulletins were sold at the “Radio One Road Show” in Bangor and at the Ulster Fleadh (traditional music festival), and a Newry band night attracted over 170 people.

A joint YAS-YRE summer camp was held in Lockheed, Boyle County, Roscommon, and lasted a week.[7] We noted the continuing success of YAS regular street activities continue in Belfast. “South Belfast comrades are to be congratulated for the vital work they carried out on the Ormeau Road during the marching season. This has enormously enhanced our reputation in the area and in the eyes of important YAS contacts”. [8]

1993: killings continue-YAS organises

The violence continued against a background of rumours of talks between the IRA and the British government. On 20th March 1993 two bombs planted by the IRA exploded in Warrington, Cheshire, England. Two children (Johnathan Ball and Tim Parry) were killed and fifty-six people were wounded. There were widespread protests in Britain and Ireland following the deaths. On 25th March the UDA/UFF shot dead four Catholic civilians and an IRA member at a building site in Castlerock, County Derry. Later the same day it claimed responsibility for shooting dead another Catholic civilian in Belfast.

The YAS bulletin of January 1993 outlined the basic demands of YAS:

- stop the killings,

- no to all forms of sectarianism and bigotry,

- stop harassment of youth,

- end injustices by the state,

- for a day of action across the North, linking schools, colleges, workplaces and local communities,

- youth unite and fight poverty, unemployment and low pay.[9]

These demands amounted to a clear call for an end to the paramilitaries and their campaigns, opposition to the state and its repressive actions, and for youth be given a future. As the January 1993 Bulletin argued “Youth Against Sectarianism… are the cutting edge of the struggle, offering not just a radical alternative to the bigots, but also to the terrible social deprivation they exploit for their own purpose”[10]

Linking Sectarianism and Racism

YAS Bulletins had prominent articles on Youth Against Racism in Europe which was launched in October 1992. In the January 1993 Bulletin there was an account of the YAS participation in the 40,000 strong Brussels demonstration which founded the YRE in October 1992. It was explained that “YAS banners were carried, and there was a speaker at the demonstration… we made the link between sectarianism and racism, two sides of the coin of bigotry and prejudice”.

It explained how it was established when anti-racist and anti-fascist fighters across the continent had come together and it had 10,000 active members in 13 countries (Austria, Belgium, Britain, the Czech lands, France, Germany, Ireland north and south, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Spain and Sweden).

In May 1993 the YRE co-organised an 8,000 strong demonstration of Black and white youth which marched on the British National Party’s (BNP) headquarters in London, following the murder of Stephen Lawrence.[11] The BNP was a fascist group which was then growing and had won a council by-election in Tower Hamlets. As organiser Lois Austin explained “It was after Stephen Lawrence was murdered that the tables really turned on the BNP It was such a terrible attack, there was a mass response, an outpouring from the local community. He was murdered in April 1993. The YRE called a demonstration on 8 May, and we had 8,000 young people turn up. It was a joint demonstration with the Black socialist campaign organisation, Panther”…

…“So then we organised a second big demonstration, in October 1993. The YRE proposed a joint demonstration of all the anti-racist organisations and the 16th October march was co-organised with the Indian Workers’ Association and the Anti-Nazi League (ANL). It was a massive demo. We knew it was going to be huge, you could feel it, such was the anger everywhere, especially in the local community. There were 50,000 people on that march”.[12]

In the spring of 1993 Youth Against Sectarianism and Youth Against Racism in Europe, mobilised for a demonstration in Coleraine protesting against the employment of Richard Lynn, a lecturer at Coleraine University and a well-known proponent of racist theories (organised by the Anti-Nazi League). The YAS/YRE leaflet demanded the withdrawal of Lynn’s research resources, a boycott of Lynn’s lectures, and pressure on the university to force them to withdraw any facilities being given to Lynn and the Pioneer fund.[13]

In 1993 new YAS groups were established in Portadown, Armagh, West Belfast, Dundonald and Cregagh in East Belfast and Coleraine. The third YAS bulletin sold over 1000.

In 1993 YAS put time and energy into countering fascism-in the autumn organising six anti-fascist public meetings, which attracted over 100 people.A YAS coach load joined the 50,000 strong anti-BNP demonstration in London on the 16th of October. We worked hard to gain trade union backing for the demonstration and gained the support of Belfast, Mid-Ulster and Letterkenny Trades Councils, Queen’s University Belfast Students Union, branches of the Amalgamated Transport and General Workers Union and the Manufacturing, Science and Finance Health Service Branch.

YAS also took up student issues, exposing the depredations of landlords in the Belfast area. The YAS Bulletin criticised the Queen’s University management, who, during November 1993 had invited church leaders to lead hundreds of students in prayer, in an effort to divert from solid actions. There were articles from school student members in Ballymena, members at Belfast Institute of Further and Higher Education, and members in Armagh. There was a note of a YAS leafletting intervention when the radical band Rage Against the Machine played at the Ulster Hall.

The 1993 YAS conference called for the extension of the Race Relations Act to Northern Ireland. The conference agreed to affiliate YAS to Youth Against Racism. The youth summer camp in 1993 was in Dungarvan County, Waterford and again, had a strong anti-racist theme. In August 1994 YAS sent a delegation to the YRE Summer Camp in southern Germany-40 activists from Ireland joined 2000 youth from 11 countries.

The guest speaker at the 1993 conference was Helen Lewis.[14][15] Helen was born Helena Katz in 1916 into a German-speaking Jewish family in Trutnov in Bohemia, Austria-Hungary (now in the Czech Republic). Following the invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1939, deportations of Jewish families began in August 1941. By the outbreak of the war, she was married and she and her husband were sent in 1942 to Terezín; in 1944 they were transferred to Auschwitz and separated. Her husband, Paul, died in 1945 on a forced march, not long before the end of the war. Helen, who survived two “selections” by Josef Mengele, was later sent to Stutthof concentration camp in northern Poland.

She talked about her experiences and the publication of her book, “A Time to Speak”. As she recalled elsewhere it had been difficult to bring up her wartime experience in her early years in Ireland: ‘Here, [in Ireland] after the war, there was total ignorance and not only that, there was a certain reluctance in people to hear talk about it, and so of course I never talked about it, as I felt it was an imposition. However, this has changed completely since my book came out in 1992”. Here in Northern Ireland certainly, there is a willingness to learn and even a certain embarrassment about past ignorance.’[1]

1993: “Bloody October”

In late 1993 there was an upsurge in violence-what became known as Bloody October when 24 people died in ten days. On 23rd October 1993 seven civilians, one UDA member and one IRA volunteer were killed when an IRA bomb prematurely exploded at a fish shop on the Shankill Road, Belfast. The IRA’s intended target was a meeting of loyalist paramilitary leaders, which was scheduled to take place in a room above the shop. The meeting had been rescheduled. In any case it was clear that the attack risked mass Protestant civilian casualties even if it was “successful” and had killed the UDA/UFF leadership.

Thousands of workers from Shorts and the Harland and Wolff shipyard marched to the scene of the bomb in protest two days later.[16] One week after the Shankill bomb, a Loyalist attack on the Rising Sun bar in Greysteel in County Derry left eight dead (six Catholic and two Protestant) and twelve wounded. The UFF claimed that it had attacked the “nationalist electorate” in revenge for the Shankill Road bombing. Workers responded with a day of mass protest across the North in which at least 80,000 took part.

We reported how, “tens of thousands have taken to the streets at the close of 1993 demanding an end to the carnage, outraged by eight days in “Bloody October”, which left 24 dead. Protest after protest developed from the mood in the workplaces and the estates. This culminated in a massive series of demonstrations across the north, from Belfast to Ballymena, from Newtownards to Cookstown, Antrim, Derry and Downpatrick. School students stood for one minute silence at 11am during the same day”.[17]

It went on “significantly, it was the trade union movement which organized this day of action. This is something YAS has always argued for”.

The example of YAS was a key factor in prompting a ‘non-political’ and school-authority approved school student demonstration against sectarianism which drew 20,000 marchers in November 1993. The organisers, keen to preserve their non-political status, called in the Royal Ulster Constabulary to have a YAS banner physically removed from the march. [18]

YAS was a threat to the school principals and the establishment because it drew attention both to the poverty and inequality which fuelled instability and violence, and because it raised the issue of state repression: “We understand what helps fuel sectarianism is poverty, unemployment, low pay and state injustices. The same features help create the conditions for racism around Europe. A serious peace or anti racist movement must take these issues on board”. We criticised the decision to allow representatives of the bosses’ organisation, the Confederation of British Industry, to speak on some of the trade union platforms”.[19]

1994: Final months of conflict

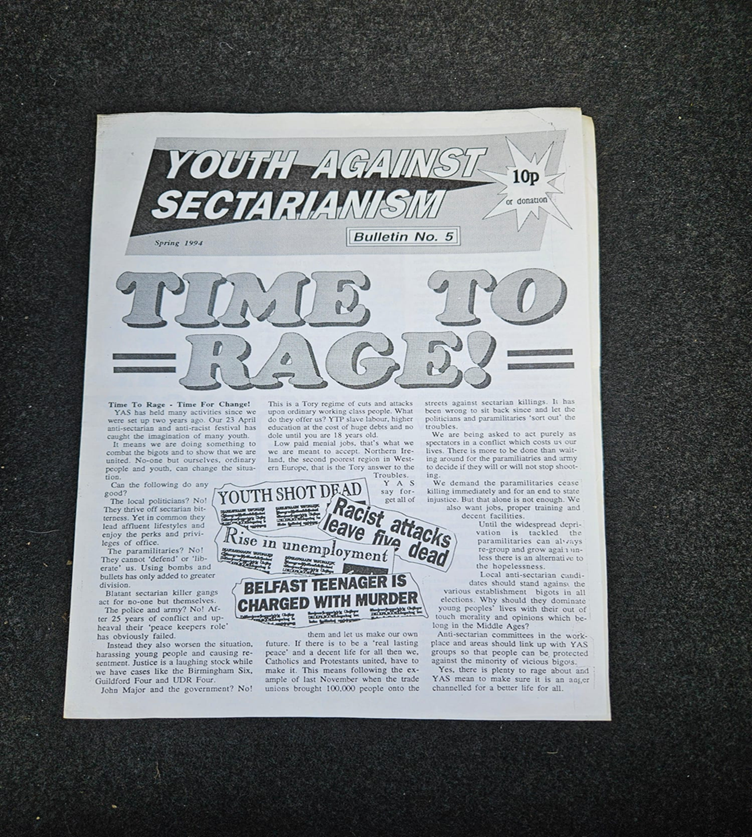

In the spring 1994 YAS Bulletin (No5) we reported on meetings in Omagh and in Belfast. The Belfast meeting had a guest speaker from the French YRE, Alia Kasab. In April, Belfast YAS met with a group of 20 trainee journalists from Norway, some of whom related their own experiences as members of the anti-racist SOS Racism organisation in Norway[20].

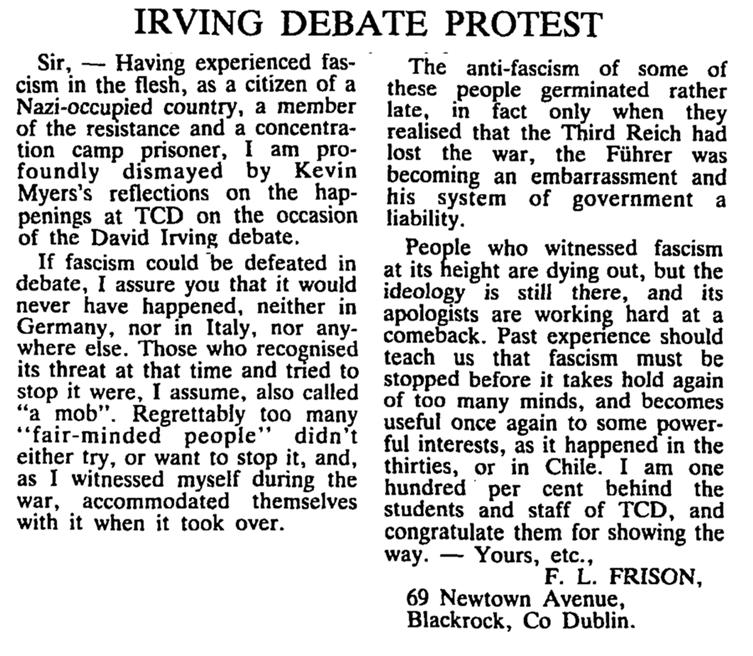

On Saturday, 23rd of April 1994 we held a conference and anti-sectarian and anti-racist festival in Belfast with the title “Time to Rage”. Franz Frison, a Belgian anti-fascist and anti-racist fighter since he was 18 years old was the guest speaker. After the Nazi invasion Frison was first imprisoned in a notorious prison for political prisoners, Breendonk[21],[22] before being transferred to Buchenwald.[23]

Franz spoke to the assembled young people to emphasise his view that fascism must be checked robustly in its infancy-points he had earlier made in writing in a frequently quoted letter to The Irish Times on 12th December 1988:

“If fascism could be defeated in debate, I assure you that it would never have happened, neither in Germany, nor in Italy, nor anywhere else. Those who recognised its threat at the time and tried to stop it were, I assume, also called “a mob”. Regrettably too many “fair-minded” people didn’t either try, or want to stop it, and, as I witnessed myself during the war, accommodated themselves when it took over … People who witnessed fascism at its height are dying out, but the ideology is still here, and its apologists are working hard at a comeback. Past experience should teach us that fascism must be stopped before it takes hold again of too many minds, and becomes useful once again to some powerful interests”.[24]

The YAS conference in 1994 called for a day of action across the North linking schools, colleges, workplaces and local communities. It argued that anti-sectarian committees should be established in the workplaces and in the estates and encouraged the setting up of YAS groups in all schools, colleges and amongst young people in general. YAS argued that such bodies could effectively build cross community confidence on the ground and help closely monitor the situation. YAS was also campaigning against the police and army harassment of youth, and against poverty, unemployment and low pay.

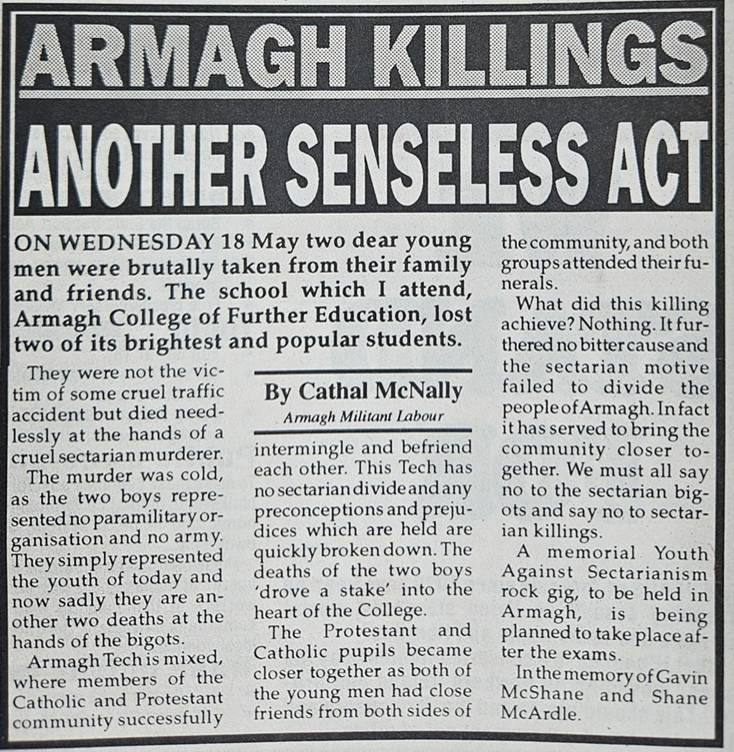

YAS Member Killed

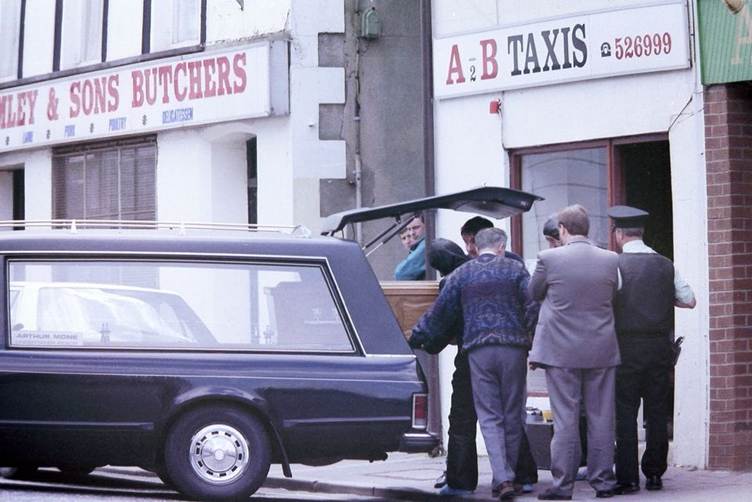

Tragically, a young man who attended YAS meetings was a victim of a sectarian murder gang. Aged only 17, he was shot dead in a gun attack in Armagh on May 18th, 1994, alongside a school friend. [25][26] Gavin Patrick McShane and Shane McArdle were shot by UVF gunman in a taxi depot in Lower English Street. They have been playing a video game with a friend. Gavin McShane died instantly, and Shane McArdle the next day in hospital. A taxi driver was wounded in the arm. Both had attended the Armagh College of Further Education and were described as the best of friends. Gavin’s mother had lost an eye in a bomb attack on the Step-In bar in 1976 in which two people died. She was three months pregnant with Gavin at the time.

YAS was active at Portadown and Armagh Technical College. In Bulletin Number 3 we had published an article from the group: “at 16 years, you can legally work and pay taxes, so you should at least be treated as thinking human beings. A college who can make their own decisions through our elected bodies. We need our own union offices… to works for these rights and to helps foster Protestant-Catholic unity in many mixed colleges”.[28]

The killing continued across the summer of 1994, for example on 16th June three UVF members were killed by the INLA on the Shankill Road, Belfast, and then two days later the UVF shot dead six Catholic civilians and wounded five others during a gun attack on a pub in Loughinisland, County Down.

On August 31st, 104 days after the deaths of Shane and Gavin, the IRA called a ceasefire and were followed several weeks later by the Loyalist paramilitaries. The IRA ceasefire broke down in 1996, and violence continued at a lower level, but the worst years were over.

Conclusions

The period 1992-1995 illustrates in practice the ways in which we successfully orientated to young people on issues of special oppression, always on a class basis. As this period came to an end with the ceasefires of the paramilitaries in 1994, we continued our anti-sectarian work but also took up issues around civil liberties (with a campaign against the in-coming Criminal Justice Bill) and over a significant period we worked with disabled activists in their determined campaign for their rights.

Youth Against Sectarianism was one of the most successful initiatives ever undertaken by Militant (later the Socialist Party) in Ireland. It reached out to 1000s of young people who attended meetings, gigs or rallies, or who read the 1000s of bulletins that we distributed over several years. The majority of those who died during the years of the Troubles were young. Many were still teenagers, or in the early years of adulthood. Young people suffered most from the mass unemployment that blighted working class areas and the majority of the more than 20,000 who went to prison for politically motivated actions were in their late teens or 20s. The Youth Against Sectarianism initiative ensured that young people had a voice in the period of intense violence. It was a “time to rage”: against the dead end of endless violence, vicious state repression, racism, homophobia, misogyny, poverty and unemployment. It was a time to engage in a struggle for a socialist future.

[1] Youth Against Sectarianism Bulletin Number 5, Spring 1994.

[2] Militant Youth Circular Number 1, 1992.

[3] Youth Against Sectarianism Bulletin Number 5, Spring 1994.

[4] Youth Against Sectarianism Bulletin January 1993

[5] Andrea Enisuoh: Tributes to community activist and journalist who worked to ‘tip the scales towards equality’ Ham and High. https://www.hamhigh.co.uk/news/21147460.andrea-enisuoh-tributes-community-activist-journalist-worked-tip-scales-towards-equality/

[6] Andrea Enisouh – a full-hearted comrade. Obituary, Militant 2020, Niall Mulholland: “It’s very sad news to hear of the passing of Andrea Enisouh. I first met Andrea in the mid-1980s when we were both Militant-supporting students in the north-west of England (Andrea in Manchester and me in Preston). How young we were – just teenagers! She was a force of nature……Andrea was a working-class fighter and one of the first Militant supporters on the National Union of Students’ national executive council. I worked with Andrea in anti-racist collaboration when I was in Belfast and Andrea in London in the early 1990s. Andrea wrote on the need for socialism to end racism in the Militant pamphlet on the legacy of US black liberation radical, Malcom X. ……A full-hearted comrade. How very sad her passing, but Andrea left her mark that will be remembered”.

[7] Youth Circular Number Six(a) 20th July 1992

[8] Youth Circular Number Six(a) 20th July 1992

[9] Youth Against Sectarianism Bulletin, Number 1 January 1993.

[10] Youth Against Sectarianism Bulletin Number 1 January 1993

[11] Hugo Pierre YRE website http://www.yre.org.uk/towerhamlets.html

[12] Ibid

[13] https://investigations.hopenothate.org.uk/history-pioneer-fund/ “History of the Pioneer Fund:Exposing the pro-Nazi organisation that financially supported 20th century race scientists”.

[14] When the war ended, she returned to Prague, where she learnt of her husband’s death; her mother, who had been deported early in 1942, had been murdered at Sobibór extermination camp. Helen began to correspond with Harry Lewis, a Czech with British nationality whom she had known at school. She married Lewis in Prague in the summer of 1947and in October moved to Belfast.

[15] “In 1992, encouraged by family and friends, she published A Time To Speak, an account of her life before the war and incarceration in a series of Nazi camps. She was 76 years of age at the time of publication. Her spare, lucid prose account…. was significant not just because it added to the growing volume of testimony by women but also in relation to the context of where and when she was writing – Northern Ireland in the 1990s. Still six years away from the ceasefire of the Good Friday agreement, the region was scarred by violence and sectarianism, and yet for her it was home, a place of refuge. Writers Mosaic from the Royal Literary Fund: Close Up A Time to Speak:26-01-2022, The Importance of Helen Lewis’s Testimony of Survival by Katrina Goldstone.

[16] Earlier in 1993, Shorts aircraft factory workers walked out after a Catholic worker was murdered on the site. Trade union representatives, including a Militant member, won the argument for action in a tense and difficult atmosphere. This united action set the scene for the later untied walkout after the Shankill bomb.

[17] Youth Against Sectarianism Bulletin Number four, Winter 1993.

[18] Youth Against Sectarianism Bulletin Number four, Winter 1993.

[19] Youth Against Sectarianism Bulletin Number four, Winter 1993.

[20] Youth Against Sectarianism Bulletin Number 5, 1994.

[21] Deem, James M. (2015). The Prisoners of Breendonk: Personal Histories from a World War II Concentration Camp. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

[22] Fort Breendonk was requisitioned by the Schutzstaffel (SS) shortly after the Belgian surrender on 28th May 1940 and used as a prison camp for the detention of political prisoners, resistance members, and Jews. Although technically a prison rather than a concentration camp, it became infamous for the poor living conditions in which the prisoners were housed and for the torture and executions which were carried out there. Most detainees were subsequently transferred to larger concentration camps in Eastern Europe. 3,590 prisoners are known to have been held at Fort Breendonk during the war of whom 303 died or were executed in the fort itself while 1,741 others subsequently died in other camps before the end of the war.In Belgian historical memory, Breendonk became symbolic of the barbarity of the German occupation.

[23] Franz Frison https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_prisoners_of_Buchenwald

[24] The Irish Times, 12th December 1988.

[25] Lost Lives: The stories of the men women and children who died as a result of the Northern Ireland troubles. David McKittrick, Seamus Kelters, Brain Feeney, Chris Thornton and David McVea. Mainstream Publishing, Edinburgh and London, 2012. p 1361.

[26] Time for Truth: The Murder of Gavin McShane, Relatives for Justice, no date. www.relativesforjustice.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/McShane-Blet-May-2…

[27] Militant [Ireland], June 1994.

[28] Youth Against Sectarianism Bulletin Number 3.