One of the discussions that took place at the last conference of Internationalist Standpoint (March 30 to April 3) was on Identity Politics (IP). This is a very important discussion particularly as IP infiltrate all colorations of the Left and present a very radical face whereas they are only a form of present-day reformism.

The discussion was based on three different texts, produced by comrades Eleni Mitsou, Ciaran Mullholland and Lucy Simpson, each supplementary to the other. In the conference discussion there was general agreement to the ideas developed in the three texts, that will be published in the form of articles in the course of the next days. According to the decision taken at the International Coordination, the three articles will be merged into one, of shorter length, and then sent out to the international organisation for discussion and amendments. The final decision will be taken by a special meeting of the delegates to the last conference, once the discussion in the national organisations has been completed.

After the publication of “Identity Politics and its role in the crisis of the Left”, the article published today is on Post colonialism and identity politics, written by Ciaran Mullholland.

Post colonialism and identity politics-a Marxist Critique

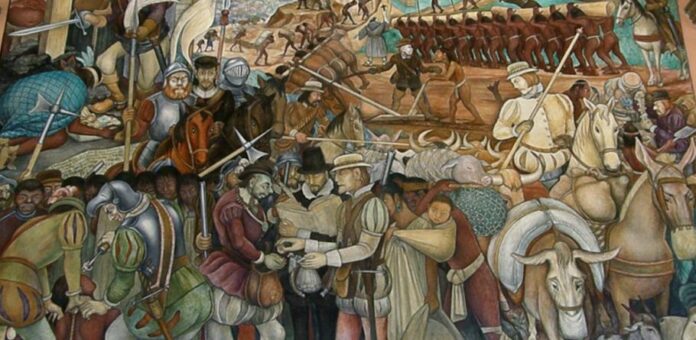

Marxism has a long tradition of seeking to explain the colonial projects of the imperial powers and the impact on the colonised peoples of the world. Marx and Engels lived in the “Age of Empires”. During their lifetimes the European continent was dominated by the Austro-Hungarian, Russian and German Empires. The Spanish and Portuguese Empires were in decline, no longer in control of the Mexico, Central and South America but the French and in particular the British Empires dominated huge swathes of the globe and had not yet reached their zenith.

Marx and Engels wrote extensively on colonisation, especially on Britain’s colonial rule in Ireland and India. Ireland has a special place in the history of colonialism as the first colony of England-a laboratory where the methods of colonialism were perfected.

Marx and Engels were aware of the racist attitudes towards Irish people which were used to justify the super-exploitation of Ireland, but they understood that at bottom England’s domination of Ireland was driven by the profit motive and was in the interest of the both the landlord class and the rising English bourgeoisie.

They drew attention both to the exploitation of the natural resources and the labour power of Ireland. When the Act of Union was sealed between Great Britain and Ireland in 1801, Ireland had a small industrial base and a growing agricultural sector. British imperialism ensured that its industries would not develop and that its agricultural sector was geared towards providing grain and beef for English cities.

The Irish peasantry was left to rely upon potatoes, which failed in the Great Famine of the 1840s. One million of the 9 million population died, and another one million were forced to emigrate. The population of Ireland continued to fall until the 1950s and today, is two million fewer than at the time of the Great Famine- no other European country has seen such a precipitous fall in its population with no recovery in the modern era. In earlier periods, the population of Ireland also fell after periods of war, pestilence and famine. It is estimated that the population fell by one third during the Nine Years War against Tudor rule (1594 and 1603) and the population fell again by a third in the Cromwellian wars (the “War of the Three Kingdoms”)in the 1640s.

Ireland’s experience of colonialism mirrors that of India and the African nations. The people of Ireland were treated as brutes and savages by the English ruling class, but this was to justify and excuse their true motive, which was not to dominate a supposedly inferior race, but to extract maximum profit.

The English ruling class exported Irish labour to the rapidly growing industrial centres of England, Scotland and Wales, and consciously promoted antagonism between workers to drive down wages. For Marx the English proletariat was not inherently racist, but he argued that it must become aware of its adoption of racist attitudes. Without this awareness, and without the English proletariat making common cause with Irish workers there would be no successful socialist revolution in Britain. And he argued, English workers must support the Irish masses yearning for an independent country.

In 1870 Marx wrote to Sigfrid Meyer and August Vogt in New York and explained:

“Every industrial and commercial centre in England now possesses a working class divided into two hostile camps, English proletarians and Irish proletarians. The ordinary English worker hates the Irish worker as a competitor who lowers his standard of life. In relation to the Irish worker he regards himself as a member of the ruling nation and consequently he becomes a tool of the English aristocrats and capitalists against Ireland, thus strengthening their domination over himself. He cherishes religious, social, and national prejudices against the Irish worker. His attitude towards him is much the same as that of the ‘poor whites’ to the Negroes in the former slave states of the USA. The Irishman pays him back with interest in his own money. He sees in the English worker both the accomplice and the stupid tool of the English rulers in Ireland.” (Letters of Karl Marx 1870 Marx to Sigfrid Meyer and August Vogt in New York).

Marx and Engels also wrote and spoke regularly on Britain’s colonisation of the Indian subcontinent. When the British East India Company began its slow but steady penetration, in a form of ‘privatised’ imperialism, there was a well-developed native textile industry based on home production. This industry was destroyed from top to bottom as industrial capitalism gathered pace in Britain. India too was ruled by fire and sword and suffered periodic famine. In India, as in Ireland and elsewhere, a conscious ruling class policy of ‘divide and rule’ favoured one group over another and sowed the seeds of future sectarian conflict and partition.

Marx did not just analyse the economic and social impact of imperial rule, but also the psychological impact of the destruction of the fabric of the old societies. In the case of India, he explained:

“England has broken down the entire framework of Indian society, without any symptoms of reconstitution yet appearing. This loss of his old world, with no gain of a new one, imparts a particular kind of melancholy to the present misery of the Hindoo, and separates Hindostan, ruled by Britain, from all its ancient traditions, and from the whole of its past history.” (Karl Marx, New-York Herald Tribune 1853: The British Rule in India).

The experience of colonisation for the colonised was both generalised, with many common features, and specific with each colony suffering its own horrors. The Congo was laid waste, and millions died to extract ivory and then rubber under the rule of King Leopold of Belgium, Germany all but exterminated the Herero people of South-West Africa (today’s Namibia) and the indigenous peoples of Australia were slaughtered and reduced to absolute poverty. In many places new settlers arrived and supplanted those who already lived on the land. The consequences of such ‘settler-colonialism’ are with us still in many places.

The October Revolution, the “Colonial Question”, and the Distortions of Stalinism

The October Revolution was for not just ‘peace, bread and land’ but for the freedom of the subject nations within the borders of the Czarist empire. For Lenin and Trotsky, the prospect of world revolution was not just a question of mobilising the proletariat of the industrialised countries, but also the masses in the colonised regions of the world.

When the Third International was founded, a clear position on the ‘colonial question’ was demanded of prospective members of the new International. Clause 8 in the Internationals Terms of Admission stated:

“Parties in countries whose bourgeoisie possess colonies and oppress other nations must pursue a most well-defined and clear-cut policy in respect of colonies and oppressed nations. Any party wishing to join the Third International must ruthlessly expose the colonial machinations of the imperialists of its ‘own’ country, must support—in deed, not merely in word—every colonial liberation movement, demand the expulsion of its compatriot imperialists from the colonies, inculcate in the hearts of the workers of its own country an attitude of true brotherhood with the working population of the colonies and the oppressed nations, and conduct systematic agitation among the armed forces against all oppression of the colonial peoples” (V. I. Lenin, July 2020. Terms of Admission into Communist International).

In the early years of the Revolution the Bolsheviks organised “the Congress of the peoples of the East” otherwise known as the Baku Conference, which was attended by delegates representing more than two dozen ethnic groups of the Middle East and the Far East. (See Baku: Congress of the Peoples of the East. Brian Pearce, trans. London: New Park Publications, 1977).

The victory of the Thermidorian reaction, and the adoption of the pernicious theory of ‘socialism in one country’ meant that the colonial masses were at the mercy of the needs of an emerging bureaucratic caste. When it was in their interests this caste gave support, including military support, to anti-colonial movements, but their support was conditional and could be dropped when the caste sought to compromise with the imperialist powers.

Nevertheless, the model of the Soviet Union was a powerful pole of attraction for the downtrodden masses in the colonial countries struggling for independence. Despite the complete absence of workers’ democracy, the achievements of the revolution-massive increases in industrial production, and gains in education and health care-suggested that a solution to the most pressing problems of food, clothing and shelter loom for the colonial masses were possible.

Post-colonialism: a product of defeats

The experience of the post-colonial period in country after country was in reality one of economic stagnation and political and social crisis. When this misery took place under the banner of regimes which declared their adherence to Marxism, the result could only be disillusionment and despair. Simultaneously the failure of the working class to seize power in any advanced capitalist country despite the revolutionary upheavals after World War Two, followed by the 25-year long post-war boom, meant that the idea that the world revolution would sweep aside capitalism, and landlordism, over time became less of a beacon to the most advanced layers in the colonial and ex-colonial countries.

By the 1980s, the Soviet Union was entering its final phase. The idea that it could overtake the United States of America in terms of economic progress and military might was no longer credible. The dead hand of the Brezhnev era smothered any attempts at free speech, never mind socialist democracy, within the Soviet Union and the satellite states. The coming to power of Gorbachev later in the 1980s presaged the end of the era of the gains of the Great October Revolution.

The collapse of the Soviet Union dealt a fierce blow to the ideas of Marxism from which they are yet to recover. It is not a surprise that in these circumstances, ideas such as post-modernism, identity theory and post-colonial theory would come to the fore, both to explain all that is wrong with the world, but also to excuse its adherents from taking on a failing system.

Neither bourgeois rule (either through ‘parliamentary democracy’ or Bonapartist dictatorship) or proletarian Bonapartist dictatorships, had solved the problems of the masses in the ex-colonial countries. In this context, the concept of ‘post-colonialism’ came to dominate academic discourse on questions of colonialism and neo-colonialism, and in time to enter the realm of politics.

Post-colonial studies are a disparate field which often employ difficult language, and it is consequently difficult to fully define. Its early origins lie in the anti-materialist philosophical ideas of ‘structuralism’, ‘post-structuralism’ and ‘post-modernism’. In the 1970s, ‘colonial discourse studies’ analysed literature in a new way, pointing out where racist ideas were half-hidden even in novels and other works which were considered to be anti-racist and anti-imperialist. Also in the 1970s, a strand of historical and sociological scholarship known as ‘subaltern studies’ developed. Colonial discourse theory and subaltern studies are the two main strands which together form the basis of post-colonial theory.

Structuralism, post-structuralism and post-modernism

To understand post-colonialism, it is necessary to first consider the roots and main arguments of structuralism, post-structuralism and post-modernism.The roots of structuralism lie in the work of early twentieth century linguists such as Ferdinand de Saussure. He and others focused on understanding words through their interrelations with other words in the structure of a language. In the 1950s and 1960s, structuralism was applied to anthropology and the study of human societies by Claude Lévi-Strauss, who argued that ‘culture’, in essence, was a structure of symbolic communication.

The structuralist approach stands in stark contrast with the materialist approach of Marxism, which understands that both language and culture arise from, and interact with, the material world. The natural environment, the techniques of labour and the forces of production designed to cope with the environment, make up the material world. There is an interplay between ideas and material reality. Understanding the material context is the guiding thread for understanding the development of ideas.

Aspects of structuralism were taken up by some self-declared Marxists, especially French Communist Party member Louis Althusser in the 1960s. He separated ideology (ideas) from political and economic structures, arguing that each has its own distinct rules and laws, independent of one another. His separation of the study of ideology (ideas) from the study of political economy led him to reject the dialectical method. In Marx’s dialectical approach, all understanding, all knowledge, is conceived of as an interconnected whole. History, the development of new modes of production, the development of classes and the state, economics, and so on must be studied together in their interconnectedness.

Structuralism began by severing language, culture and ideas from material processes. This approach was developed and deepened as structuralism evolved and then was taken further by the ‘poststructuralists’ in the late 1960s and 1970s. Among the more prominent thinkers and writers in the field were Michel Foucault (who wrote on madness, sexuality and power), Jacque Derrida and Jacque Lacan (a psychoanalytical thinker). Post-structuralism retained the key aspects of structuralism-an emphasis on ‘discourse’ (ideas, words, language etc) being fundamental, and the argument that it is possible to understand discourse without connecting it with other parts of the social world (or reality). The post-structuralists added a new idea: the view that “power” is more diffuse than is claimed by Marxists who emphasis the role of the capitalist state. Instead, they adopted a variety of existential and psychological approaches in their attempt to ‘understand’ the world.

Poststructuralism was influenced by postmodernism. Postmodernism rejects any explanatory models which it considers to be a “grand narrative”-that is an attempt to draw together disparate phenomena and historical periods to explain human society. Marxism is of course one such “grand narrative” and was rejected by postmodernist thinkers and increasingly by the poststructuralists.

Colonial Discourse Theory

Postcolonial theory developed in the late 1970s and 1980s by drawing on these theoretical tools to explain colonialism and postcolonial relations between the “advanced capitalist countries” (ACCs) and the former colonies. Most postcolonial theorists accept the argument that ideology, discourse and culture are in some sense primary-that is separate and independent of material forces.

Post-colonialism has a specific focus on the identity that distinguishes colonised peoples from colonising peoples. Frantz Fanon was an important forerunner to this school of thought: he was a French Martinique psychiatrist who devoted his life to the cause of the Algerian revolution. Before his premature death of leukaemia at the age of 33 he wrote several books which have become classics, especially Black Skin White Mask and The Wretched of the Earth, with its famous foreword by Jean Paul Sartre, which celebrated revolutionary violence as an end in itself, in order to overturn centuries of colonialism, not just politically, but psychologically (see The Wretched of the Earth, Penguin Modern Classics, 2001 and Black Skin, White Masks, Penguin Modern Classics, 2021).

Fanon had very clear views as to which classes in society would lead the revolution, ideas that are entirely at odds with Marxism. He had certainly read Marx, and quoted him occasionally, but his work was much more influenced by the existentialist phenomenology of Sartre. He was associated with the ideas of ‘Third Worldism’, exaggerating the role of the peasantry and the dispossessed of the colonial and ex-colonial world (the lumpen proletariat) whilst downplaying the role of the working-class or proletariat.

Writers in the colonial discourse tradition draw attention to the one-sided, pro-Western and often racist writings of multiple writers over several centuries. Post-colonial literary theorists have, of course, added something to human knowledge, exposing as they have an often-hidden racist prejudice, sometimes voiced by those who were expressing opposition to aspects of colonial policy. One example is Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, an exposé of the horrific regime of the Belgian King Leopold in the late 19th century (and inspiration for the film Apocalypse Now), but which contains within racist tropes.

The most prominent writer in this field is Edward Said, whose 1979 book, Orientalism, is widely read and very influential (Said, Edward W: Orientalism: 2003 Edition, 25th Anniversary, Penguin Books). Said was an American-Palestinian academic, and by the end of his life, was very prominent both in academic and political circles. The idealism which underlines his approach is exemplified by his argument in 1993, at the time of the first Gulf War, that America would not have invaded Iraq if it had properly understood the Arab psyche. This denial of the social, economic and political reasons which are always the underlying cause of war, whatever the proximate cause, illustrates the anti-materialism of the post-colonial school of thought.

Postcolonial studies aim to broaden curricula to include writers from the former colonies and to critically contrast Western representations of the colonies with self-representations of colonised peoples. Said identified how literature often depicts the West as a beacon of science, secularism and liberalism, and the Orient as backward and superstitious. He argued that such prejudices were present not only the writings of those who were pro-imperialist and colonialist in outlook, but also the writings of Marx and Engels. In Said’s view no true representation of anyone’s reality is possible and all attempts are a distortion of facts reflecting the agenda of the writer. Said did not ignore material factors but the subsequent trend of postcolonial theory, in particular in the writings of Gayatri Chakravarty Spivak and Homi Bhabha has been to adopt the anti-materialist ideas of Derrida and Lacan.

The Subaltern Studies Group

In the 1970s, the Subaltern Studies Group (SSG) in India began to explore the history of the “subaltern” on the Indian subcontinent. The term subaltern was first used to describe British Army officers of the lower ranks (from the Latin ‘below everyone’). The Subaltern Group adopted the concept from Antonio Gramsci who used it to designate proletarian and peasant classes denied access to political representation or a voice within government by the fascist Italian state (Selections from the Prison Notebooks of Antonio Gramsci by Antonio Fo Gramsci, 2005).

The SSG used subaltern to mean peasants, landless rural workers and other layers in India who were the most downtrodden and powerless in society (reflecting the caste system). Much of the work of the subaltern group is important: it draws attention to huge movements of the peasant class in India under British rule and other related phenomena. Written accounts of peasant uprisings involving hundreds of thousands of peasants and other downtrodden layers on the Indian subcontinent are invaluable.

The early group did not entirely ignore class or Marxist ideas but quickly began to develop a new analysis. The SSG argues that social relations are different in the ex-colonial world, and that the Marxist analysis of class society does not apply in the strict sense. The Marxist view is that whilst human cultures differ, all have been shaped by the same underlying processes. In all societies humans must deal with problems of producing and reproducing society within the natural and human-made environment. Any variation, caused by a myriad of factors, does not change this fundamental truth. The Group do not accept this, and they and those who came after them have developed ideas that are consciously anti-Marxist and anti-materialist. These ideas have now been adopted by important identity politics adherents.

The SSG also argue that politics in India (and in other ex-colonial countries) is fundamentally different from politics in the West. They reject both liberal and Marxist social theory, which in their view developed to explain and understand Western societies but are inadequate for understanding how capitalism has developed in the postcolonial world. Subalternists generally agree with the idea that the bourgeoisie (in what are now the advanced capitalist countries) was a revolutionary class in its time, leading a struggle to overthrow the aristocracy. The bourgeoisie then instituted “modern politics”, with a form of parliamentary democracy, political liberties, individual rights, separation of church and state (secularism), and bourgeois culture, where people’s consciousness and motivations are framed in terms of individual self-interest. The bourgeoisie also played an historical role in leading nation-building projects.

Where the subalternists disagree with Marxists is on the role of the bourgeoisie in the colonised regions of the world. Marxists argue that as the Western bourgeoisie colonised the rest of the world, it initiated similar changes everywhere. It attempted to abolish feudal relations, and at least paid lip service to the introduction of bourgeois democracy. The bourgeoisie of the colonising country did not usually initiate nation-building, but it was assumed that the native bourgeoise of the colony would do so once it had gained independence from the empire.

The subalternists argue that in the colonies the bourgeoisie (either colonial or native) did not abolish feudal relations but instead compromised with the feudal class. As a result, power is not in the hands of the capitalist class alone but is shared with pre-capitalist classes. As a result, pre-capitalist political forms also remain in place, and community, honour, ethnicity, and religious duty, or as important as individual interests or class interests in day-to-day life.

All this means that postcolonial societies are not on the same road to modernity as the West. Instead, modernity has more than one form. The West and the postcolonial world are fundamentally different, and it is not possible to explain both with the same theoretical framework, either liberal or Marxist, with a few simple additions or qualifications. For the subalternists the differences are profound and therefore require new theoretical categories. The subalternist reject the very possibility of generalising about societies around the world. Marxism, in contrast, whilst acutely aware of differences, seek to generalise.

Post-Colonial Theory and Identity Politics

Post-colonialist thought has become pervasive, especially in universities, and is often contrasted to Marxism. One prominent post-colonial thinker Nivedita Majumdar (professor of English at John Jay College, CUNY, New York) has summarised its claims:

“Among critical and progressive academics today, the influence of postcolonial theory is unmistakable. Though born in the narrow confines of literature departments in the wake of Asian and African decolonization, its intellectual apparatus has increasingly become associated with more directly political commitments. Postcolonial theory today is viewed as an indispensable framework for understanding how power works in modern social formations and, in particular, how the West exercises its dominance over the Global South.

Even more, it is lauded for its attentiveness to the marginal, the oppressed — those groups that have been relegated to obscurity even by political traditions ostensibly committed to social justice. On elite university campuses, the concepts associated with this theoretical stream have increasingly displaced the more traditional vocabulary of the Left, particularly among younger academics and students.

Indeed, the two most influential political frameworks of the past century on the Left, Marxism and progressive liberalism, are often described not just as being inadequate as sources of critique, but as tools of social control”

(Nivedita Majumdar, Silencing the Subaltern, Catalyst, Vol 1, No 1, 2017)

It was not long before authors in the identity politics field began to use the term subaltern to mean all people who are deemed to be the equivalent of colonised people. Depending on the author this may include not just gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender people, but all women. This can lead to complex formulations around the “sexual subaltern” which are very difficult to fully grasp, for example, in “The Sexual Subaltern and Law: Postcolonial Queer Imaginaries” (Ratna Kapur in Enticements: Queer Legal Studies, May 2024) the editor asserts that:

“Ratna Kapur retrieves forms of gendered and sexual subjectivity and subculture unassimilable either to colonial mandates or to LGBT legal advocacy, while she is cautious not to indulge in a precolonial nostalgia for the fantastically queer past. Kapur examines recent judgments of the Supreme Court of India on LGBT rights, as well as the political movements surrounding those judgments, to consider sexual dissidence and sexual subalternity foreclosed by queer victories, rights talk, and what she identifies as a stubbornly enduring ‘heterosexual presumption.’”.

The Marxist Critique of Post-colonialism

Post-colonial theory views the modern world through a focus on the racism of white people. It pays less attention, and sometimes no attention, to the nature and origin of imperialism and the role of the drive for profit. Post-colonialists argue that the social structure of post-colonial societies (the persistence of a large peasant class, a class that disappeared in the advanced capitalist countries at a much earlier stage in the development of capitalist relations) leads to the conclusion that Marx’s analysis does not apply. Secondly, they assert that the experience of the colonised and the coloniser is so different that the former cannot comment meaningfully on the latter. This targets all Western commentators, including Marxists, who are therefore not entitled to comment beyond very general points. Some go further and seek to explain the actions of the colonisers as a result of deep-seated and long-standing racist attitudes which implicate everyone (all classes) in the coloniser country and hold all responsible for colonisation.

In recent years, these ideas have reached a peak of influence and have become even more distorted and divorced from reality. They are, of course, completely at odds with the historical materialist and dialectical materialist approach of Marxism. The leading theorists in the field of post-colonialism are often consciously and vocally critical of Marxism. Whilst writers in the field of subaltern studies have produced important and useful works on, for example, peasant uprisings on the Indian subcontinent, the general thrust of post-colonial studies is anti-Marxist, anti-materialist, anti-scientific and anti-Enlightenment (the Enlightenment being the period in the late 18th century which prefigured the French Revolution).

Marxism is an evolving science, and will always seek to learn from new developments, both in the natural sciences and the social sciences. When these new developments seek to interpret reality in ways which are non-dialectical and anti-materialist, then Marxism has much less to gain or to learn from these approaches. Marxists in the advanced capitalist countries should take care to acknowledge and understand the psychology of the colonised peoples but this does not mean that Marxists are not entitled to analyse and to put forward political perspectives for ex-colonial countries. This must be done with care, especially when Marxists live in an ex-coloniser country and comments on politics in an ex-colonial country. Marxists in this situation, would be wise to heed the warnings of Lenin against great Russian chauvinism, present even within the ranks of the Bolshevik Party.

Marxism remains the only frame of reference which explains imperialism and colonialism, and which points a way forward from the misery of the lives of the bulk of the world’s population who live in the ex-colonial countries. There are no answers for the poor and most oppressed rural layers in the ex-colonial countries who are seeking a way out of their misery in the ideas of post-colonialism.

There is nothing in the writings or in the theories of post-colonialism which is superior to Marxism, or which provides a coherent explanatory model, or a guide to action. The Marxist analysis explains why the colonies existed and showed a pathway through struggle towards genuine freedom. The post-colonial theorists do not point in the direction of struggle or towards any solution to poverty and unemployment, which is the lot of the masses in the ex-colonial countries, particularly the youth. It can be said of post-colonial studies that what is useful in this field is not new, and what is new is not useful. In other words, whilst detailed studies of the experience of colonialism from the perspective of the colonised is an important contribution, the retreat from an understanding of human society based on class and capital means that post-colonialism is a barrier to progress.